Collecting polar bear footprints to map family trees

- Published

Scientists from Sweden are using DNA in the environment to track Alaskan polar bears.

The technique which uses DNA from traces of cells left behind by the bears has been described as game changing for polar bear research.

It's less intrusive than other techniques and could help give a clearer picture of population sizes.

Environmental DNA (eDNA) comes from traces of biological tissue such as skin and mucus in the surroundings.

Scientists and now conservationists are increasingly using such samples to sequence genetic information and identify which species are present in a particular habitat.

It's often used to test for invasive species or as evidence of which animals might need more protection.

In another application of the technique, geneticist Dr Micaela Hellström from the Aquabiota laboratory in Sweden worked with WWF Alaska and the Department of Wildlife Management in Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) to collect snow from the pawprints of polar bears.

They tested the technique on polar bears in parks in Sweden and Finland.

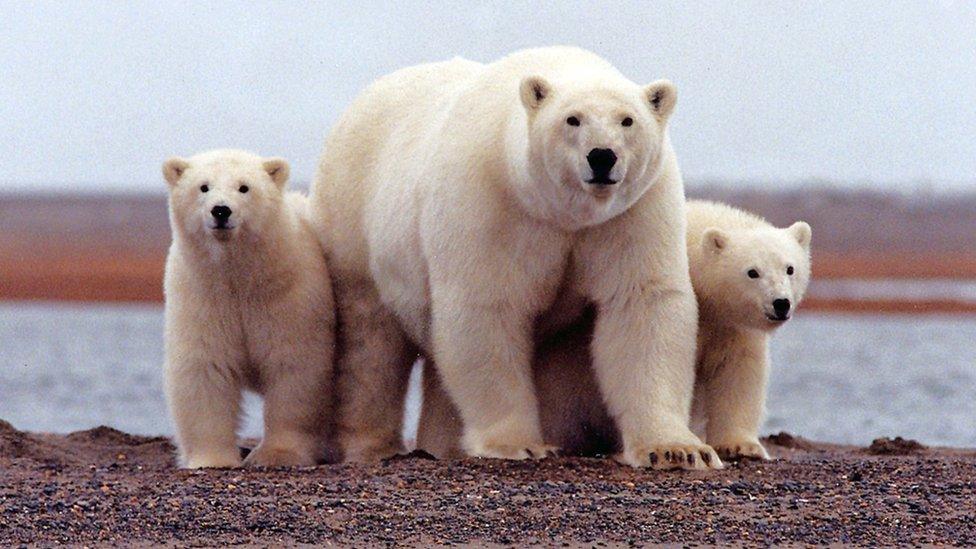

Environmental DNA could give a better indication of polar bear population sizes

"We realised that for the first time we could reach the nuclear DNA within the cells. The material outside the cell can tell what species you are and there are 1,000 or 2,000 copies. But the DNA in the nucleus which identifies an individual has only two copies, so it's an enormous challenge to get out enough from these snowsteps," she said.

"It's the same principal as paternity tests in humans."

The team also worked with the local Iñupiat population which mainly exists on hunting and fishing and also wants to ensure there is a healthy population.

Dr Hellström said: "They really want to take care of their environment and they don't like when scientists come and sedate the polar bears and take blood tests because they think it will affect the animals and it's very, very intrusive.

"So we thought the method of finding the tracks is not dangerous for the scientists or the polar bears."

Challenging conditions

Environmental DNA is broken down by ultraviolet (UV) light from the Sun so the team decided to work in the dark.

But conditions were very windy and temperatures could plunge to -40C. Principal investigator Andrew von Duyke from Alaska's Department of Wildlife Management said: "Polar bears live in remote areas with extreme weather conditions, spending most of the time on very dynamic and dangerous sea ice and we had to be vigilant.

"We travelled out by snowmobiles with the Iñupiat hunters and benefited directly from their skills and expertise. A great deal of this work would not be possible without them."

But the extreme cold also changed the polar bears' behaviour.

"We realised it was so cold the polar bears moved differently to those in the parks - they looked like they were dancing," says Dr Hellström.

"They get long hairs under their feet so they don't get cold. I was worried. To get DNA out of the hair you need the hair sacs and it doesn't give as strong a sample, so we had to collect 40-50 steps from each bear."

Keeping watch for polar bears

Clear signals

Dr Hellström continued: "We realised we actually got very clear signals and sequences from the nucleus to identify individuals which is a very, very big thing.

"It was a very risky project because no one has succeeded in doing this before and it's still early days. But now we have the proof of concept, so we can work on this and hope to have the first full individuals within a year."

Members of the Iñupiat population will also be trained to take samples in future. Dr Von Duyke explained: "It means the local community - which already knows a heck of a lot about polar bears - is included in management efforts.

"The team hopes to work with WWF in Russia to look at polar bears in the entire Arctic region and plot family trees, assess the population size and map migration routes to show the impact of climate change."

You can hear more on this story and how "environmental DNA" is transforming what we know about the natural world on Costing the Earth on Radio 4 at 15:30 BST or on BBC Sounds.