The battle to break plastic's bonds

- Published

The new process turns polyethylene into motor oil

When Kenneth Poeppelmeier opened the reactor vessel in his lab and saw liquid, he said it was a real "eureka moment".

"All of us were so excited," he told BBC News.

Prof Poeppelmeier and his colleagues at Northwestern University in Illinois, US, have developed a chemical technique which breaks down the bonds that make polyethylene - the plastic most commonly used to make the ubiquitous carrier bag - so indestructible.

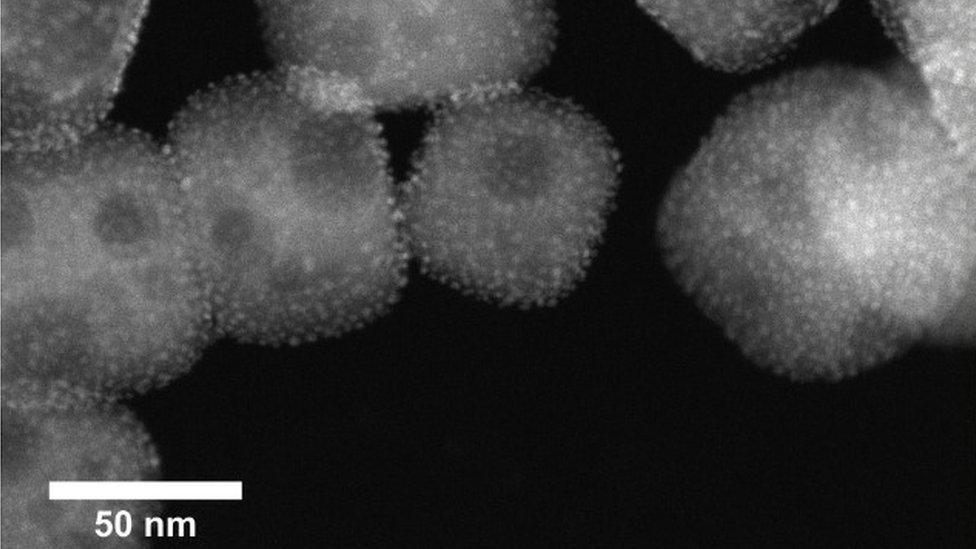

The process "chops up" the plastic polymer, turning it into liquid oil. His team published their breakthrough in the journal ACS Central Science, external. It is a clever catalytic technique using metal nanoparticles to essentially snip the polymer apart - chemically transforming it into a liquid.

Platinum nanoparticles 'chop up' the polyethylene, chemically transforming it into liquid

"Importantly, that liquid has use and value," says Prof Poeppelmeier, who says his team - including collaborators from Argonne National Laboratory and Ames Laboratory - are now testing how it performs as a lubricant.

"It's important to understand that these materials - all this plastic packaging - has a value. We certainly shouldn't be throwing it into the environment, but we shouldn't be throwing it away or burning it either."

While the approach has promise, it is in its early stages - it does not mean we will all be pouring a liquid form of recycled carrier bags into our cars any time soon. Similar approaches, though, are attracting investment to tackle a huge technological and environmental quandary - how can plastic waste be made into something useful and more valuable?

Transforming trash into treasure

Science reporter Victoria Gill looks at why there is so much plastic on beaches

Chemists - the chemical industry, in particular - are racing to make use of the mountain of single-use plastic building up in our environment. Meanwhile, more than a million tonnes of new plastic are created worldwide, every day.

The strong bonds that link together the long chains of many commonly used plastic polymers are the fundamental reason for their incredibly useful properties. They are the physical backbone of plastic's strength and durability. But this means they are also the reason for its now infamous longevity - they are why plastic takes so very long to degrade.

So transforming that tide of plastic waste into something of higher value - fuels or new materials - is a promising business venture. It is called chemical recycling - and is distinct from purely mechanical recycling. That's what we are largely reliant upon when we throw our plastic packaging into the recycling bin. Currently, plastics are sorted into their different types, melted down and made into pellets, which can be used to make new objects out of that same type of plastic.

This process also degrades the material, so there's a finite number of times that a plastic bottle can be recycled in this way.

Chemical recycling creates something chemically different - something new and useful. "We need chemical recycling as part of how we deal with waste in the UK," says Prof Michael Shaver from The University of Manchester and Henry Royce Institute.

But, he explains, it has lagged behind mechanical recycling because it is so much more energy intensive.

"Even this more efficient study (by the scientists at Northwestern University) requires a process at 300C for more than 30 hours.

"But chemical recycling has promising potential when waste streams are mixed - when we have lots of different types of plastics in the bin.

"If we can convert these materials together, there is real value in the product as we avoid the need to separate things."

About 20% of plastic waste in the UK is mechanically recycled

Industrial plastic tactics

Most of the endeavours in this area are in industry, where new ventures and existing chemical giants are trying to develop techniques that can, on an industrial and profitable scale, break down plastics into either fuels or feedstocks - chemicals which can be fed back into a plant to produce brand new plastics.

There are some relatively new, ecologically branded UK-based ventures like Recycling Technologies and Plastic Energy, which has plans to build 10 new plants in Europe and Asia by 2023. These companies use technology based on using high heat in the absence of oxygen to break down a mixture of plastics into fuel. Other ventures are using various methods of "depolymerisation" - breaking one hardy polymer down into its constituent fragments, so it can be fed back into a plant to make brand new plastic products.

Because much of the investment in this area is from industry, external, many new technologies being developed are not yet public knowledge.

In reality, Prof Shaver says, chemical recycling - though promising and important - will be just one piece in the monstrous puzzle of how we effectively make good use of all that plastic waste.

"Many plastics are efficiently mechanically recycled," he says. "This needs to be maintained - but when we cannot do that, we can turn to this new strategy for turning these strong bonds into a useful feedstock."

- Published1 October 2019

- Published19 July 2017

- Published18 December 2018