Nasa probes oxygen mystery on Mars

- Published

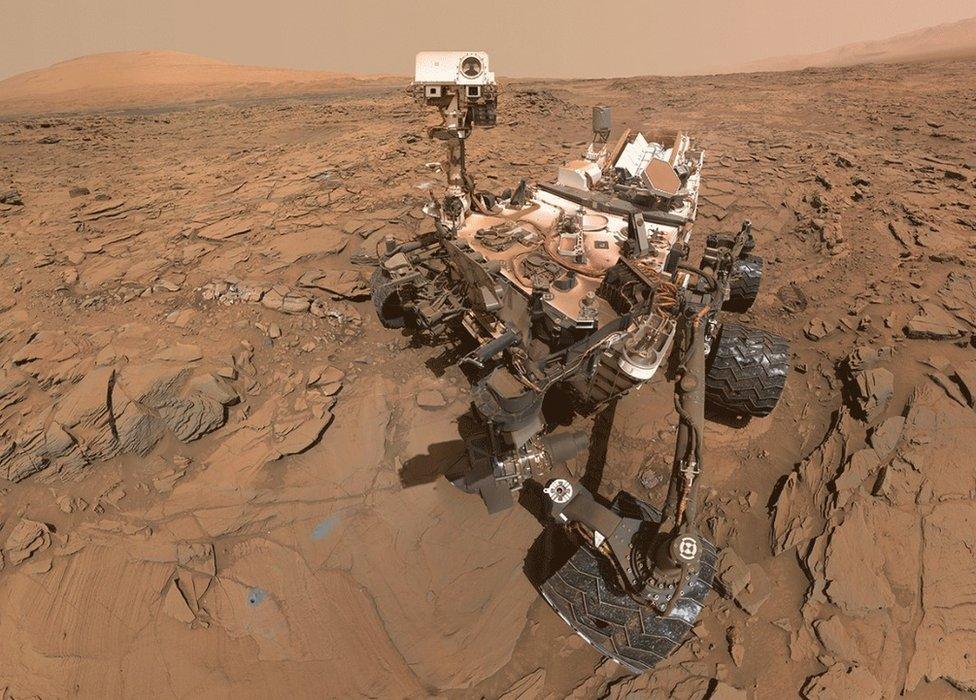

Curiosity has been exploring Gale Crater, which once hosted a body of liquid water

The oxygen in Martian air is changing in a way that can't currently be explained by known chemical processes.

That's the claim of scientists working on the Curiosity rover mission, who have been taking measurements of the gas.

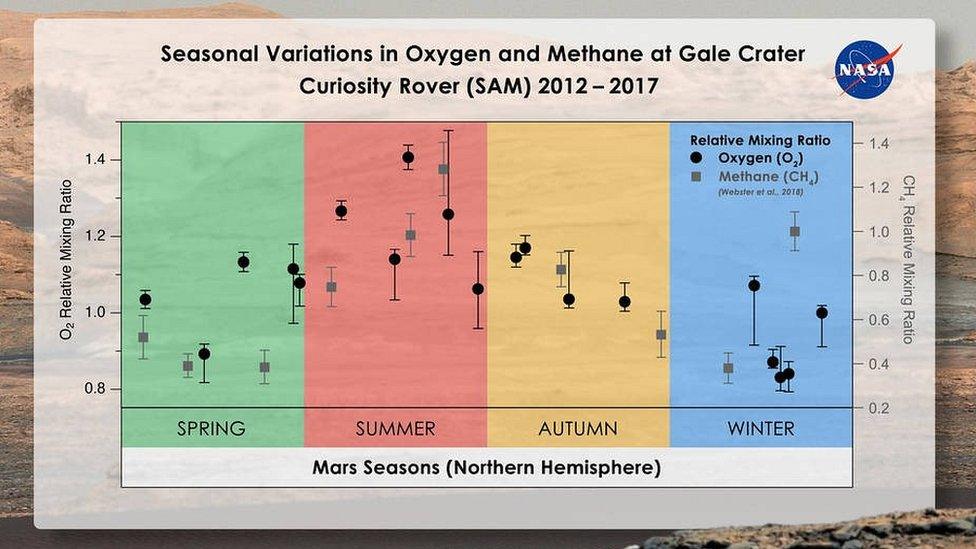

They discovered that the amount of oxygen in Martian "air" rose by 30% in spring and summer.

The pattern remains a mystery, but researchers are beginning to narrow the possibilities.

While the changes are most likely to be geological in nature, planetary scientists can't completely rule out an explanation involving microbial life.

The results come from nearly six Earth years' (three Martian years') worth of data from the Sample Analysis at Mars (Sam) instrument, a portable chemistry lab in the belly of the Curiosity rover.

The scientists measured seasonal changes in gases that fill the air directly above the surface of Gale Crater on Mars, where Curiosity landed. They have published their findings in the journal JGR-Planets., external

The Martian atmosphere is overwhelmingly composed of carbon dioxide (CO2), with smaller amounts of other gases such as molecular nitrogen (N2), argon (Ar), molecular oxygen (O2) and methane (CH4).

Nitrogen and argon followed a predictable seasonal pattern, changing according to how much CO2 was in the air (which is in turn linked to changes in air pressure). They expected oxygen to follow this pattern too, but it didn't.

Oxygen rose during each northern hemisphere spring and then fell in the autumn.

They considered the possibility that CO2 or water (H2O) molecules released oxygen when they broke apart in the atmosphere, leading to a short-lived rise. But it would take five times more water than there actually is to produce the additional oxygen, and CO2 breaks up too slowly to generate it over such a short time.

"We know oxygen is created and destroyed on Mars through the energy provided by sunlight breaking down CO2 and H2O, both of which are observed in the atmosphere of Mars. The thing that doesn't make sense is the size of the variation - it doesn't match what we expect to see," Dr Manish Patel, from the Open University - who was not involved with the study, told BBC News.

"Given that Curiosity makes measurements at the surface of Mars, it is tempting to think that this is coming from the surface - but we have no evidence for that. Geologically-speaking, it seems unlikely - I can't think of a process that would fit."

The results may point to a reservoir of oxygen close to the Martian surface

Dr Timothy McConnochie, from the University of Maryland in College Park, who is one of the authors on the JGR-Planets paper, told the BBC: "You can measure the water vapour molecules in the Martian atmosphere and you can measure the change in oxygen... There just aren't enough water molecules.

"Mars in general has a pretty small amount of water vapour, and there's several times more oxygen atoms that mysteriously appear than there is in the water vapour on the entire planet."

They also considered why the oxygen dropped back to levels predicted by known chemistry in the autumn. One idea was that solar radiation could break up oxygen molecules into two atoms, which then escaped into space. But after running the numbers, scientists concluded it would take at least 10 years for the oxygen to disappear in this way.

In addition, the seasonal rises aren't perfectly repeatable; the amount of oxygen varies between years. The results imply that something is producing the gas and then taking it away.

Dr McConnochie thinks the evidence suggests a source of oxygen in the near-surface. "I think it points to a reservoir (of oxygen) in the soil that interchanges with the atmosphere," he said.

"To exchange (with the atmosphere) fairly rapidly on a seasonal timescale it has to be close to the surface. If it's deeper, any process is going to be slower," he told BBC News.

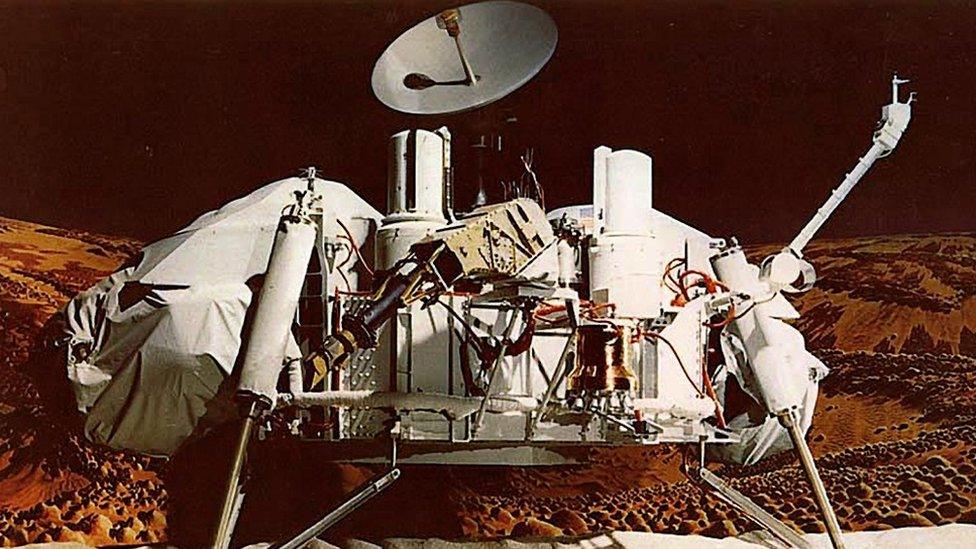

An experiment carried out by the Viking landers in the 1970s provides tantalising clues in the oxygen mystery

Some supporting evidence for this comes from Nasa's Viking landers, external, which touched down on the Red Planet in the 1970s. Results from the Viking Gas Exchange Experiment (GEX) showed that when the humidity was increased in a chamber containing a sample of Martian soil, it led to a release of oxygen.

However, says Dr McConnochie, the temperature in the Viking spacecraft chamber was much warmer than it would be outside, even during spring and summer. This complicates any attempt to apply the results to the Martian environment: "It's a tantalising clue, but it's not helping us solve the problem directly," he explained.

Mars does become more humid during spring and summer. Water-ice gets deposited on the poles during the winter. Then, throughout the summer, there is a release of water vapour in the polar regions.

There could be a link between the humidification of the entire planet at this time and the release of oxygen.

Intriguingly, the changes in oxygen are similar to those seen for methane, which increases in abundance by about 60% in summer for inexplicable reasons. It's unclear whether there's any connection though.

Soil sink

The methane mystery has attracted much attention over the years because most of Earth's methane is produced by living organisms. Though there are several ways that methane could be released by geological processes on Mars, the production of this gas by microbes living deep beneath the surface remains a tantalising possibility.

Oxygen, too, can be produced by microorganisms. The possibility that biology is behind the changing levels of the gas in the Martian atmosphere can't be ruled out. But the scientific bar on such claims is set very high indeed.

It's a very remote possibility, but we still don't understand enough about the behaviour of oxygen to use it as an indicator for life.

In addition, the near sub-surface of Mars is a very difficult place to live because of the high levels of radiation that leak through the Martian atmosphere, large variations in temperature and limited availability of water.

"With current instruments on Mars spacecraft, we have no way of knowing whether biology is producing the springtime rise in oxygen. Abiotic processes look very promising, so we'll need to firmly rule them out first before pursuing microbial contribution," Prof Sushil Atreya, from the University of Michigan, who is a co-author on the study, told BBC News.

But he added that future missions would make interrelated measurements that could shed light on Martian habitability.

Dr Manish Patel says that oxygen can last for years in the Martian atmosphere

Dr Patel said: "Whilst I believe biological activity in the Martian sub-surface at some point in Mars' history is a real possibility, there is no way to explain this through oxygen-producing microbes - we are missing the copious other indicators that would come along with that.

"Maybe it's all hidden, but as a scientist, I can only comment on what we observe - and an extraordinary claim requires an extraordinary observation."

The notion of oxygen being locked up in some chemical form in the Martian soil remains much more likely.

"One phenomenon that applies to most gas molecules is they stick to surfaces... especially anything with a lot of surface area. That sticking, that adsorption, changes on the basis of temperature," Tim McConnochie explained.

"Oxygen is a very active molecule, so it changes to some other form and then sticks and then changes back. The tricky thing is the forms of oxygen we know about in the Martian soil are the ones that are pretty stable."

One of these stable molecules is a compound called perchlorate, which is widespread in Martian soil. It doesn't give up its oxygen easily, but it's possible that exposure to high energy radiation - cosmic rays, for example - could make some of it break down, leaving by-products.

One potential by-product is hypochlorite - found in bleach - which is less stable and thus more prone to releasing its oxygen.

"I feel we're closer to an idea of how to release it from the soil than we are to an idea of how to sequester it back into the soil," said Tim McConnochie. But he explained: "Presumably there is some cycle that sequesters it."

Prof Atreya explained: "There are at least three potential abiotic reservoirs of oxygen in the surface/subsurface of Mars - oxidant, in the form of perchlorates; oxidant in the form of hydrogen peroxide; and oxidised rocks or hydrated minerals.

"Water-rock reactions in the past, or even today if liquid water exists beneath the surface or as brines, were most likely responsible for the third reservoir."

Dr Patel believes it may not be possible to apply the result from Gale Crater to the whole of Mars. "This has been highlighted by the recent methane measurement, where Curiosity measured a huge amount of methane, but it wasn't detectable by the NOMAD and ACS instruments on the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, which makes measurements of these things at a global-scale and at higher sensitivity."

The authors of the study in JGR-Planets say they are throwing out the problem to scientists in the field, in a bid to harness expertise from across the community.

We've learned huge amounts about the Red Planet over the last few decades, but it's clear from this there are still lots of puzzles to crack.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external