Supernova 1987A: 'Blob' hides long-sought remnant from star blast

- Published

This Hubble Space Telescope image shows Supernova 1987A within the Large Magellanic Cloud

Scientists believe they've finally tracked down the dead remnant from Supernova 1987A - one of their favourite star explosions.

Astronomers knew the object must exist but had always struggled to identify its location because of a shroud of obscuring dust.

Now, a UK-led team thinks the remnant's hiding place can be pinpointed from the way it's been heating up that dust.

The researchers refer to the area of interest as "the blob".

"It's so much hotter than its surroundings, the blob needs some explanation. It really stands out from its neighbouring dust clumps," Prof Haley Gomez from Cardiff University told BBC News.

"We think it's being heated by the hot neutron star created in the supernova."

When telescopes first spotted the explosion in 1987, it caused huge excitement.

Sited in the Large Magellanic Cloud, some 168,000 light-years from Earth - the blast was the nearest, brightest supernova seen in the night sky in 400 years.

As such, it's become the test case for what we think we know about stars when their fuel runs out and they suffer a cataclysmic collapse.

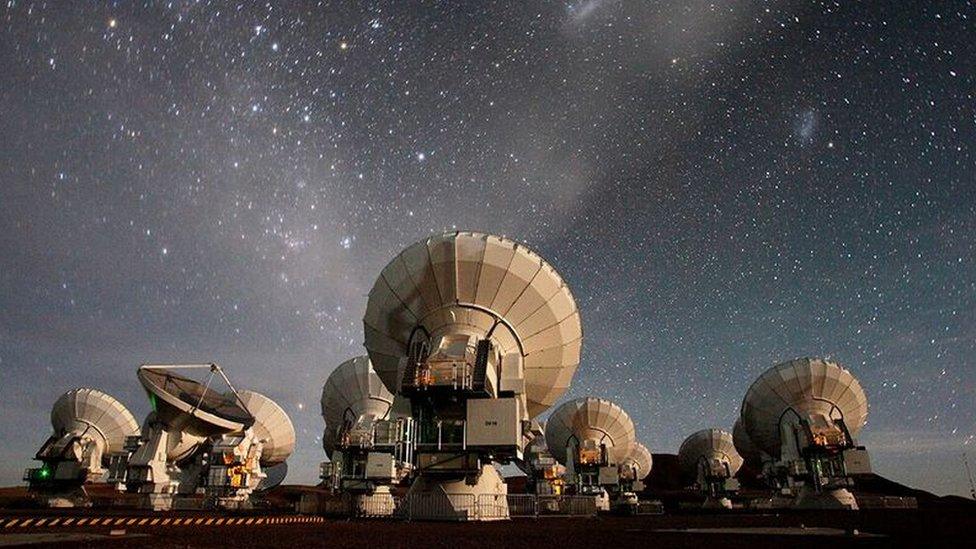

The team used the Alma facility to study the dust and gas at the heart of Supernova 1987A

Three decades on, astronomers routinely observe Supernova 1987A and its constantly developing form.

It is a thing of beauty: it has a series of bright rings that represent bands of gas and dust thrown out by the star in its dying phases and which have since been excited by the expanding shockwaves emitted in the end-moment explosion.

One of these rings looks like a string of pearls, and it's at the centre of this celestial jewellery that the scientists reckon they've now located the star remnant.

It should be a dense object composed entirely of neutron particles and measuring just a few tens of kilometres across. The thick cloud of dust in which it sits, however, is perhaps 30 times the size of our Solar System and this makes the neutron star impossible to see directly.

"We see the recycled light, if you like. The hot neutron star heats the dust grains and as they absorb that energy - they shine at sub-millimetre wavelengths. That's what we detect," explained Prof Gomez.

The team has been probing the area of interest using data from Europe's now defunct Herschel space telescope and the international Atacama Large Millimeter Array (Alma) facility in Chile.

Alma has the resolution to tease out the important details

What Alma in particular reveals is that the blob also resides in a region deficient in carbon monoxide (CO) molecules. The CO is being destroyed, presumably in the same heating process that's making the dust shine.

Unfortunately, it's difficult to be more descriptive about the neutron star because of its dust shroud, but the group expects this to change with time.

In maybe 50 to 100 years, the dust should clear to reveal the object's true guise.

A paper detailing the new findings is published in The Astrophysical Journal, external. Its lead author is Cardiff's Dr Phil Cigan.

He told BBC News: "The amazing thing about [Supernova 1987A] is that we are watching the changes in real time, seeing how it evolves over months and years. It's like watching the plot develop in the acts of a play.

"By monitoring its progress, we can compare the reality to what different models predict, and we are eagerly anticipating seeing the direct radiation from the neutron star when the dust thins out."

Astronomers are interested in supernovas because they are integral to the evolution of the Universe.

The explosions stir up the environment, nudging nearby gas clouds to gravitationally fall in on themselves and birth new stars. The dust ejected in supernovas also seeds the cosmos with the heavier elements that go into building rocky planets.

Artwork: The neutron star at the centre of "the blob" is a few tens of km across