UK set for 'active' role at European space meeting

- Published

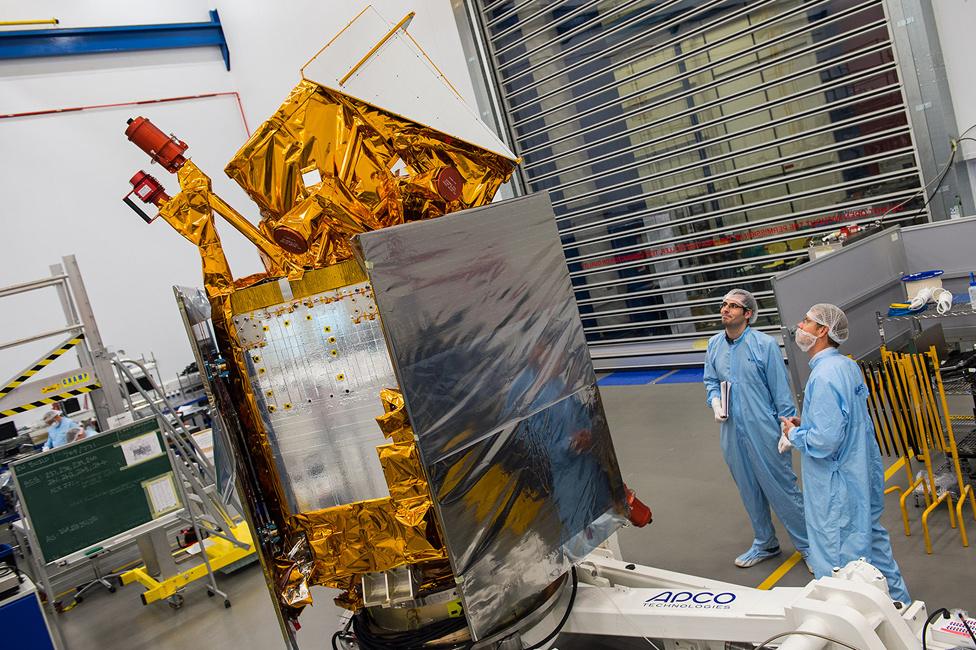

Europe is building a big network of Earth observing satellites called the Sentinels

It now looks highly likely that the UK will increase its subscription to the European Space Agency.

For the past week the long-promised uplift in the country's membership fee had appeared extremely doubtful.

Such a reversal would have threatened leadership roles in a number of space missions and denied British industry some lucrative R&D contracts.

But the UK government indicated to Esa late on Tuesday that it was ready to move forward with negotiations.

A spokesperson for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis) said: "The UK has a world-leading space industry. As a founding member and one of the main contributors to the European Space Agency, we have sent a UK delegation to the ministerial conference to participate actively in discussions."

It hasn't been confirmed officially, but the BBC understands the UK is set to increase its €355m (£305m) annual subscription by "more than 15%".

Subscriptions turn into R&D investments that keep Europe globally competitive

The negotiations here in the Spanish city of Seville should see Esa's 22 member states approve an overall package of programmes worth €12.5bn (£10.7bn; $13.8bn). The final figure will be announced on Thursday.

This money will cover a range of activities from new Earth observation satellites to joint missions to the Moon and Mars with the United States.

Esa's triennial councils at ministerial level always start with some kind of drama, or argument, and this time it's been the UK's turn to be at the centre of it.

The country has been saying for some months that it intended to spend more money in Esa. "If Esa didn't exist, someone would have to invent it," Science Minister Chris Skidmore told this year's UK space conference.

But it's understood the Prime Minister's office raised a number of questions last week about the appropriateness of an increased subscription, especially in an election period, and how the subscription would fit with a proposed national space programme.

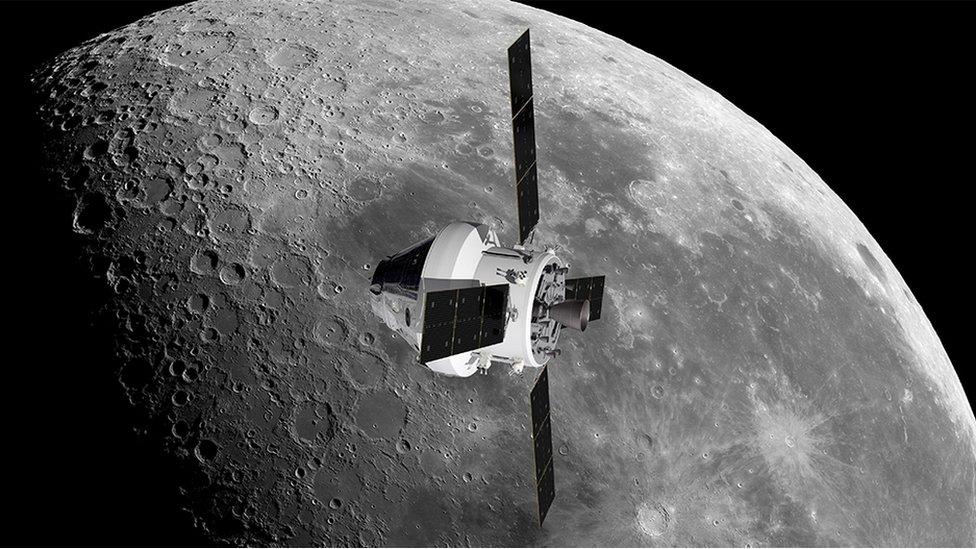

Artwork: Europe is supplying the back end to the Americans' Orion crewship

Officials have spent recent days responding to those questions and, seemingly, reassuring No 10.

UK industry has been lobbying hard for a subscription increase.

Businesses say the R&D investments that flow back into the home space sector are vital to its global competitiveness.

Britain builds a quarter of the world's big telecommunications satellites, for example. It's a major reason why Esa also bases its telecoms technical centre in Oxfordshire.

Esa is often confused with the European Union. The organisations are actually separate legal entities and although the majority of their member states are the same, there is not a complete overlap.

What can €12.5bn buy at Esa?

Agency officials are putting a broad package of proposals before member states to approve. Apart from the mandatory contributions to the agency's running costs and its general science programme, nations can pick and choose which projects to back and at what level. These are some of the areas member states can bid into.

Human spaceflight and robotic exploration - This is a near-€2bn programme that aims to put Esa directly in the US space agency's (Nasa) grand plan to return astronauts to the Moon - known as Artemis. Member states are being asked to fully fund two propulsion units for the Americans' Orion crew capsules, and to pay to start development work on modules that would attach to a lunar space station called Gateway. Mars exploration also features in this budget line. Esa wants to bring rock samples from the planet back to Earth for study in the laboratory. Technologies for this include a surface rover that UK engineers would very much like to build.

Earth observation - The package on the table is worth close to €2.4bn. The key component, valued at €1.4bn, would kick off the next phase of the Copernicus Earth observation programme. This is the most ambitious civil EO venture in the world and has seen a suite of satellites being launched in recent years to take a health check on the planet. The new phase, to be approved in Seville, would start the development of another six Sentinels, as they are known. Copernicus is a complex programme, not least because it's run in partnership with the EU. British industry believes it has the capacity to lead the R&D on two of the proposed Sentinels, but this will very much depend on how much money the UK puts on the table.

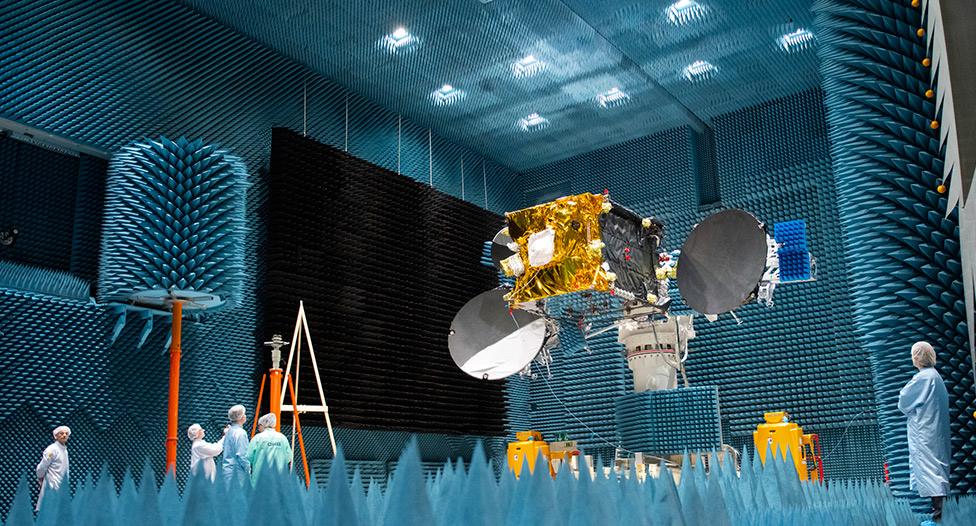

Telecommunications - This €1.7bn programme has been very successful in the past in leveraging matching private investment. The programme supports the innovations that go into the next generation of commercial telecommunications satellites, which bounce TV, data, phone calls and broadband internet around the world. A key initiative here in Seville is an effort to develop technologies that can transmit information via laser light. Satellites generally make their connections through radio links, but these are becoming something of a bottleneck, especially when compared with the capabilities of the fibre infrastructure on the ground. If satellites could make greater use of optical transmissions, it would keep them on the innovation pace.

Space transportation - This line is worth almost €2.7bn. This has been the most fractious area in past Councils as Europe has debated how best to meet the competitive challenge of the US rocket industry. Member state companies - principally in France, Germany and Italy - are working on two new vehicles, one called Ariane 6 and the other Vega C. They'd loft the smallest to the biggest satellites on the market. Crucially, the rockets should be much cheaper to build and operate. This meeting will approve funds to finish their development and to open new R&D projects to boost their future competitiveness. This would include technologies to allow a rocket to be used more than once.

Space safety - This area, worth €600m, is all about protection - of space infrastructure and of Earth itself. On the list is a satellite known as Lagrange that would stare at the Sun to warn of outbursts that could damage other spacecraft and interfere with radio communications and power grids on Earth. This project is of primary interest to the UK. At the last ministerial council, member states rejected an asteroid encounter mission. The decision drew criticism because of our need to study objects that could hit - and devastate - the Earth. In response, Esa is putting forward a new mission for subscription called Hera. This small probe would visit a space rock that had previously been bombarded by a Nasa mission to learn more about how threatening asteroids could be deflected.

Science programme - Valued at €2.8bn, all member states must contribute to the projects that fall under this umbrella. Science spending in the agency has been depressed at recent councils, receiving only "flat cash" settlements. This time, the intention is to give the budget area a stronger-than-inflation rise - at 10%. One of the benefits would be to provide the funding necessary to accelerate some exciting missions a decade from now. Esa is building a big X-ray space telescope called Athena and a constellation of satellites, known as Lisa, that could detect the gravitational waves from colliding black holes. It would be best if they could be flown at the same time to study events in the cosmos in tandem. The money promised at this council should make that possible.

The BBC invited Labour, the Lib Dems, SNP and Brexit parties to give their positions on perhaps the most contentious area of the meeting - Copernicus, because of its large EU involvement. The Lib Dems said they were supporters of Copernicus and lauded the "ground breaking technology" it had brought to the near real-time detection of flooding; Labour said it too backed continued collaboration on what it called "vital" EU programmes. The SNP and the Brexit Party have yet to come back to us.

Europe is in the process of upgrading its rocket systems

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external