Boeing astronaut Starliner capsule lands after incomplete mission

- Published

Starliner spacecraft returns early after failed mission

The Boeing company has cut short the uncrewed demonstration flight of its new astronaut capsule.

The Starliner launched successfully on its Atlas rocket from Florida, but then suffered technical problems that prevented it from taking the right path to the International Space Station.

It appears the capsule burnt too much fuel as it fired its thrusters, leaving an insufficient supply to complete its planned mission.

Starliner came back to Earth on Sunday.

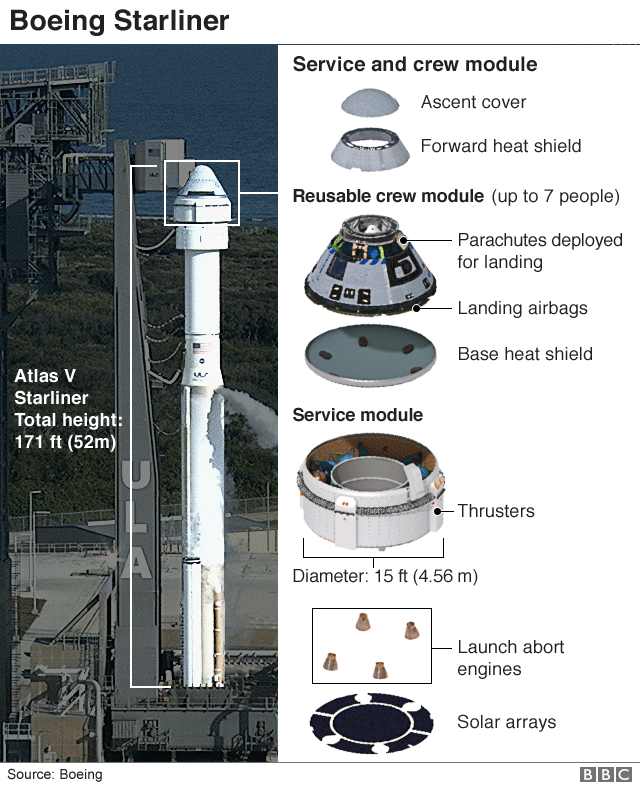

It landed in New Mexico's White Sands testing range, using parachutes and airbags to make a soft touchdown on desert terrain.

It marked the first US land-landing for this type vehicle. Past crewed capsules have always made splashdowns in the ocean.

Boeing and the US space agency (Nasa) must now review the truncated mission before deciding when to allow crew to fly aboard future Starliners.

While this automated demonstration ticked off many of its objectives, such as a safe entry, descent and landing - it failed to achieve other key ones, the most significant being a rendezvous and docking with the space station.

Artwork: The capsule ticked off many of its mission objectives - but failed to get to the ISS

The Administrator of Nasa, Jim Bridenstine, said in a press conference on Friday that Starliner had experienced a timing "anomaly" shortly after launch. This led the capsule to become confused over where it was in its mission sequence. Starliner then expended an excessive amount of propellant trying to maintain very precise pointing, or attitude.

Flight controllers recognised the problem but were unable to intervene quickly enough because the capsule was passing between satellite links.

Mr Bridenstine remained upbeat, taking the positives out of the day's events.

"A lot of things went right," he said. "This is why we test."

The Administrator then suggested that had astronauts been in the capsule, they could have helped re-direct the craft to the space station.

Nasa astronaut Mike Fincke, who has already been selected to fly on a future Starliner, agreed with this assessment.

"Had we been on board, we could have given the flight control team more options on what to do in this situation," he said.

Not since 2011, when the shuttles were retired, have Americans launched from their own soil; US astronauts have been hitching rides in Russian Soyuz capsules instead.

The capsule launched on an Atlas rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida

The Starliner, and another capsule called Dragon from the SpaceX company, have been developed to reinstate the capability.

The business model will be different from the past, however.

Instead of owning and operating the new capsules, Nasa will simply buy seats in the craft. And Boeing and SpaceX will also be free to sell any spare capacity to others - to other space agencies and commercial concerns.

The agency "seeded" Starliner and Dragon under its Commercial Crew Program (CCP). The companies were given milestone payments to encourage the development of their capsules.

The vehicles are late, however; they should have been flying in 2017.

Mike Fincke and Nicole Mann are looking forward to flying in Starliner

That they are still at the demonstration stage is due in part to Congress squeezing the amount of money Nasa could spend on the initiative. But also because of technical set-backs, such as the explosive destruction of a Dragon capsule on a test stand.

The SpaceX craft does look closer to entering service, though, after completing its own uncrewed trial in March. Whether Boeing will now have to repeat its test flight, going all the way to the station, before it can join Dragon on the "taxi rank" is uncertain. "I think it's too early to make that assessment," Mr Bridenstein said.

It's still possible Boeing and Nasa may decide to move directly to crewed flights.

Mike Fincke's Nasa astronaut colleague on the upcoming Starliner mission will be Nicole Mann. "We are looking forward to flying on Starliner. We don't have any safety concerns," she commented.

- Published6 November 2019

- Published16 October 2019