UK meteorite hunt thwarted by equipment damage

- Published

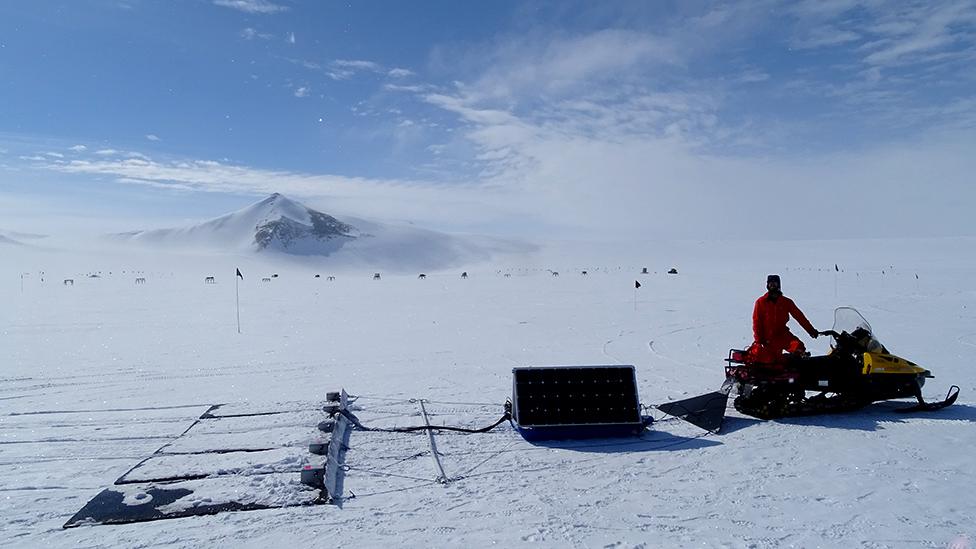

The detection system took a beating as it bounced across the hard, rough ice

UK scientists' bid to find a hidden population of iron meteorites in the Antarctic has been beaten into submission.

The University of Manchester team had developed a detection system it hoped would reveal the metal objects sitting just under the ice surface.

But after 18 days of survey work, the equipment has broken beyond repair.

It seems the components couldn't cope with the pounding they received as the detector was dragged across hard ice.

"This constant battering from the ice meant that anything which could fail did, and once repaired as best we could, a weakness in components remained for further exploitation," expedition co-lead Dr Geoff Evatt reported on Wednesday, external.

The scientists had been trying to test a theory that would explain why so few iron meteorites turn up in Antarctica compared with the rest of the world.

This theory holds that the metal objects warm up in the sunshine and melt themselves down into the ice and out of view.

The bespoke detector - modified from the technology used to locate land mines - was designed to sense the iron down to a depth of a few tens of centimetres.

The team went with two systems to be dragged behind snowmobiles. Both rapidly picked up damage as they bounced over the frozen, undulating terrain of the Outer Recovery Ice Fields.

The project as a whole has recovered more than 100 meteorites

But while the scientists discovered no hidden metal meteorites on their trip, they have bagged a large haul of stony space rocks that were sitting proud of the surface.

Just after the patched up detector finally broke for good, Dr Evatt came across a 65th find. And that's on top of all the objects picked up in a reconnaissance effort a year ago.

"It thus looks like we have almost certainly collected over 100 meteorites for return to the UK, all ready to be examined for their scientific worth and hopefully put on public display," said Dr Evatt.

The team isn't quite finished yet. The Manchester researchers - who include Drs Katie Joy and Romain Tartese, and engineer Wouter Van Verre; as well as British Antarctic Survey (BAS) guide Geraint Raymond - will continue the surface search until 16 January.

At that point, a BAS plane will come to pull the scientists out of the field so they can begin the long journey home.

The detection array was tested in the Arctic and elsewhere in the Antarctic

A review of the "Lost Meteorites" project will no doubt commence once the group is back in Manchester.

Clearly, it will reflect on the robustness of the detection system. The conditions encountered in the search area this year were far rougher than those experienced during testing and development work undertaken in the Arctic and elsewhere in the Antarctic in previous years.

That not a single sub-surface iron meteorite was detected on this trip should not be surprising. These objects are extremely rare anyway, and in the difficult conditions of recent weeks the team was able to cover only a fraction of its expected search area.

Before the trip, the scientists thought they might detect up to five irons if they could survey 15-20 sq km. In the end, less than 1 sq km was searched.

Meteorites trace their origin to the asteroids and smaller chunks of rocky debris left over from the formation of the Solar System 4.5 billion years ago. As such, they have much to tell us about the conditions that existed when the planets came into being.

The irons in particular are interesting because they represent the smashed up innards of those early planetary bodies that grew big enough to have metal cores, just like Earth has today.

But you have to be lucky to find an iron meteorite, especially so in Antarctica. Less than 1% of all the space rocks recovered in searches on the White Continent are of the metal type, compared with about 5% elsewhere in the world.

In the Antarctic, Iron meteorites account for 0.5% of all meteorite finds

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external

- Published29 November 2019

- Published18 March 2019

- Published27 February 2019

- Published28 March 2018

- Published17 February 2016