Coastal floods warning in UK as sea levels rise

- Published

Storm Ciara brought widespread flooding

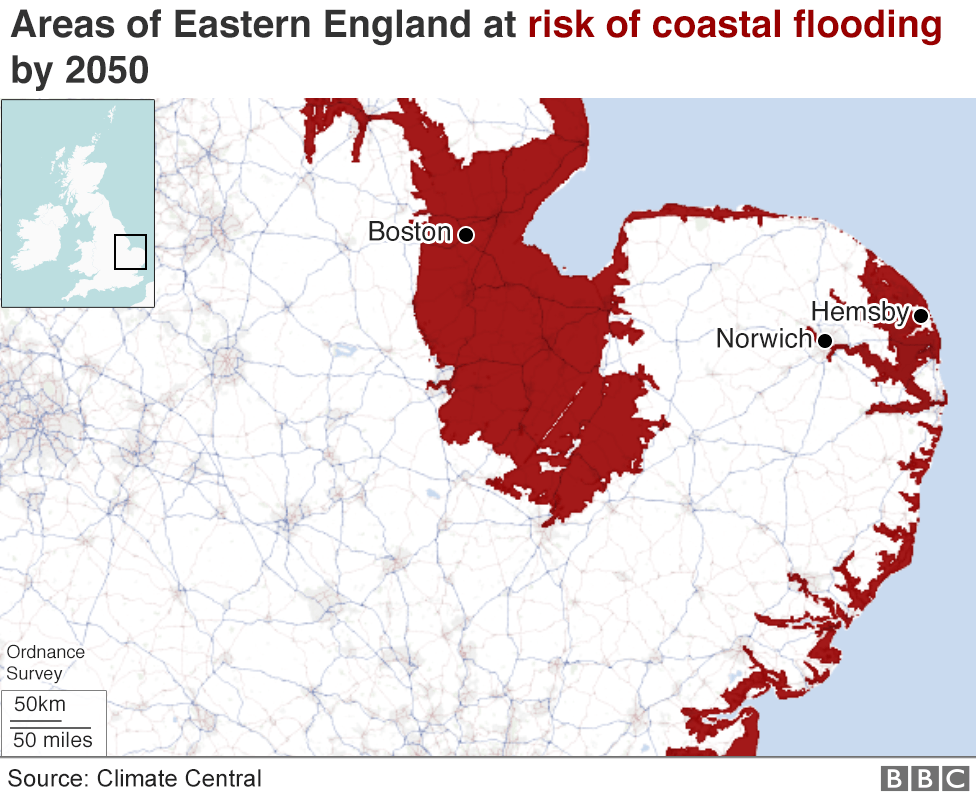

Coastal communities face "serious questions" about their long-term safety from rising seas, a senior Environment Agency official has warned.

People have become used to a "myth of protection", according to John Curtin, head of floods and coastal management.

"We are in a cycle of thinking we can protect everywhere always", he told BBC News.

His warning follows research suggesting polar melting is accelerating and raising the height of the oceans.

And a major UN study last year said extremes of coastal flooding are set to become far more frequent.

What's this warning all about?

Mr Curtin is taking a long view about how climate change is set to increase the level of the sea and alter the coastline.

As a leading specialist in flood defence in England, he wants to trigger a public debate about how to respond.

He believes that since the 1960s, when huge concrete embankments were built along many stretches of shore, several generations have grown up taking coastal protection for granted.

Now, he says, there's an urgent need for 'difficult conversations' about how to respond to the prospect of much higher seas.

In some locations that will mean bigger, stronger defences but in others the conclusion may be that it's better for people to move inland.

"If the seas rise by another metre, they get more stormy, there are some places that are really vulnerable.

"We might need to look at where people live eventually."

What does he have in mind?

Mr Curtin was speaking as he guided me around a new flood scheme in Boston in Lincolnshire, a town repeatedly hit by North Sea storm surges in recent decades.

Each surge was higher than the last - in 1953, in 1978 and in 2013 - and every time the response was to improve coastal defences by raising embankments.

The most recent flood hit 500 homes and 300 businesses and caused £1m worth of damage to Boston's famous St Botolph's church, known locally as the Stump.

It led to a massive project to defend the town with a tidal barrier, now under construction at a cost of more than £100m.

A smaller version of the Thames Barrier which protects London, the scheme involves a steel wall that can be raised into position to hold back the sea if a storm surge is forecast.

Doesn't that fix the problem?

Yes, for several decades at least. Mr Curtin describes the Boston barrier as "brilliant" - and one of many new schemes around the country.

But he is concerned about the long-term future even for somewhere that's well-defended.

The new barrier is designed with sea level rise in mind - about 1.5m higher than the last 2013 surge - but there is a risk that climate change will prove more rapid than expected.

Building the Boston barrier

"What if sea level rise happens faster? What do we do beyond the next Boston scheme…"

This isn't just a question of cost, although the sums involved are huge. It's also a practical issue, of whether gigantic engineering is the best answer.

"You can keep building higher and higher walls but if you've got a wall that's 10, 15, 20m above a community, is that really where people want to live?"

Why is coastal flooding such a threat?

Of all forms of flooding, an inundation on the coast has long been seen as the most dangerous.

When there's intense low pressure, the sea itself is raised in a giant bulge and if it's driven ashore by strong winds and also coincides with a high tide, the effects can be devastating.

A storm surge in 1953 worked its way down the East Coast wrecking towns and villages and killing more than 300 people.

And the latest climate science makes clear that the heating of the planet will add to the threat.

The global average sea level is rising by more than 3mm a year.

This is partly because water expands when it warms - what's known as "thermal expansion" - and also because the ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are melting.

In the worst-case scenario, the oceans could be about one metre higher by the end of the century.

And the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded last year that extreme coastal floods that are currently expected once every 100 years could strike every year by 2050.

What about places that are unprotected now?

This is one of the most sensitive questions of all.

Unlike Boston, the village of Hemsby on the Norfolk coast is too small to meet the government's criteria to get funding for flood defence.

So there's nothing to stop the biggest storm surges racing across the beach and tearing into a sand dune on which many homes are built.

The village of Hemsby is too small to meet the government's criteria to get funding for flood defence

Over the years, houses have been undermined and have either fallen into the sea or have had to be demolished, and local people fear that worse is to come.

Lorna Bevan Thompson, who owns a pub in Hemsby and helps to run a campaign group, says she's pleased that Boston is being helped but says her community is also under threat.

"It's a real danger to us all now," she told me.

"We have no protection from the sea coming into our villages and flooding all our areas.

"When you see it going, it breaks your heart."

The dune is being reinforced with concrete blocks, but there's a limit to the protection it can offer

She argues that although Hemsby's population is only about 4,000, the village, as a tourist resort, generates tens of millions of pounds for the economy.

A former soldier, Lance Martin, lives in what appears to be Hemsby's most vulnerable home, perched on top of the dune close to the sea.

A recent storm surge gouged out the sand from under his house and forced him to shift the structure ten metres inland for safety.

He's tried to reinforce the dune with concrete blocks and old telegraph poles but there's a limit to what he can do on his own.

"There's nobody else that's going to do job for me," he says.

The reality is that the geography of our island nation has always shifted, a process set to accelerate with further rises in sea level.

Inevitably, in the choices about where to save, there'll be winners and losers, which is why John Curtin hopes a national dialogue will begin soon.

"If we don't start having those conversations now, in fifty or a hundred years the sea will take them anyway."

Follow David on Twitter., external

.