Nasa's InSight probe senses hundreds of 'Marsquakes'

- Published

InSight's seismometer package sits under a protective dome

Things go bump on Mars on a fairly regular basis. That's the conclusion of a year of listening for quake signals on the planet by the InSight lander.

The US space agency-led probe has detected over 450 significant seismic events since touching down in 2018.

None are particularly big - at most, they're only 3 to 4 on the magnitude scale, which you might feel if you were standing directly above the tremors.

The quakes' size and frequency is actually not that dissimilar to the UK.

The important message though to take away from the first detailed reports on the progress of the InSight mission, external is that Mars is far from being a dull, dead planet; it's an active one, says principal investigator Bruce Banerdt.

He told reporters: "We finally for the first time have established that Mars is a seismically active planet and that the seismic activity is greater than that of the Moon, which was measured back during the Apollo programme, but less than that of the Earth (as a whole).

"In fact, it's probably close to the kinds of seismic activity you would expect to find away from the plate boundaries on the Earth and away from highly deformed areas."

That's pretty much the quake picture in Britain "give or take a factor of two", added Tom Pike from Imperial College London.

A magnitude 4 event in the UK will occur on average roughly every two years.

InSight arrived on Mars on 26 November 2018, touching down in an equatorial region of the planet known as Elysium Planitia. It settled in a small crater that has been informally named Homestead Hollow.

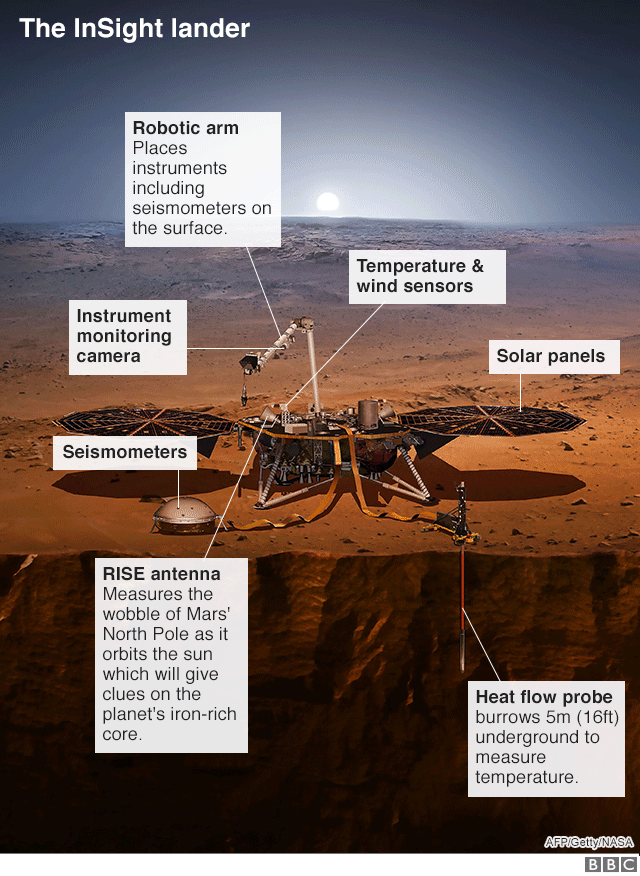

In addition to its French-UK seismometer package, the probe is equipped with a heat sensor that aims to burrow into the ground, and an exquisite radio experiment that will measure how the planet wobbles on its axis.

Taken together, Insight's data should reveal the position and nature of all the rock layers below the surface of Mars - from the crust to the core. It's information that can then be compared and contrasted with Earth.

The results released on Monday - and published in a series of papers in Nature and Nature Geoscience, external - represent just the early phase in this science quest which could take some years to fulfil.

Mars shows no obvious evidence of plate tectonics, of great slabs of rock jostling across its surface, which is the driving mechanism of quake activity on Earth.

Instead, much of the quake behaviour on the Red Planet is likely the result of cooling and contraction. As Mars loses heat, it shrinks and its brittle outer skin then fractures in response.

The probe's seismometers, although representing just a single station, do have some ability to locate the source of the bigger quakes and in Monday's published catalogue there are a number of events that have been pinpointed to a nearby terrain referred to as Cerberus Fossae.

This is an area of Mars that satellite imagery has suggested may have experienced volcanism in the geologically recent past. In other words, within the last 10 million years.

"It's possible that there's actual magma at depth that's cooling," speculated InSight deputy project scientist Suzanne Smrekar.

"And as that (possible) magma chamber contracts, it causes deformation of the strong part (of the crust) - the lithosphere.

"We don't have information from our quakes that say that this is what's going on. It's a hypothesis of how we connect what we see at the surface to the fact that we are observing Marsquakes in that region."

Some modelling is required to trace the quakes back to Cerberus Fossae. That's in part because, so far, the mission still doesn't have great velocity data for the propagation seismic waves through Mars' rocks.

"We need to know what the velocities are to properly work out a distance," explained Prof Pike whose team developed the high-frequency sensors in InSight's seismometer package.

"To do that we need either to unambiguously locate the quake separately, which we could do from a meteorite strike, but we haven't detected one of those yet; or by having a strong enough event that the waves would go around the planet twice, which is what most earthquakes on Earth do. And because we know the diameter of the planet - that would give us a calibration," he told BBC News.

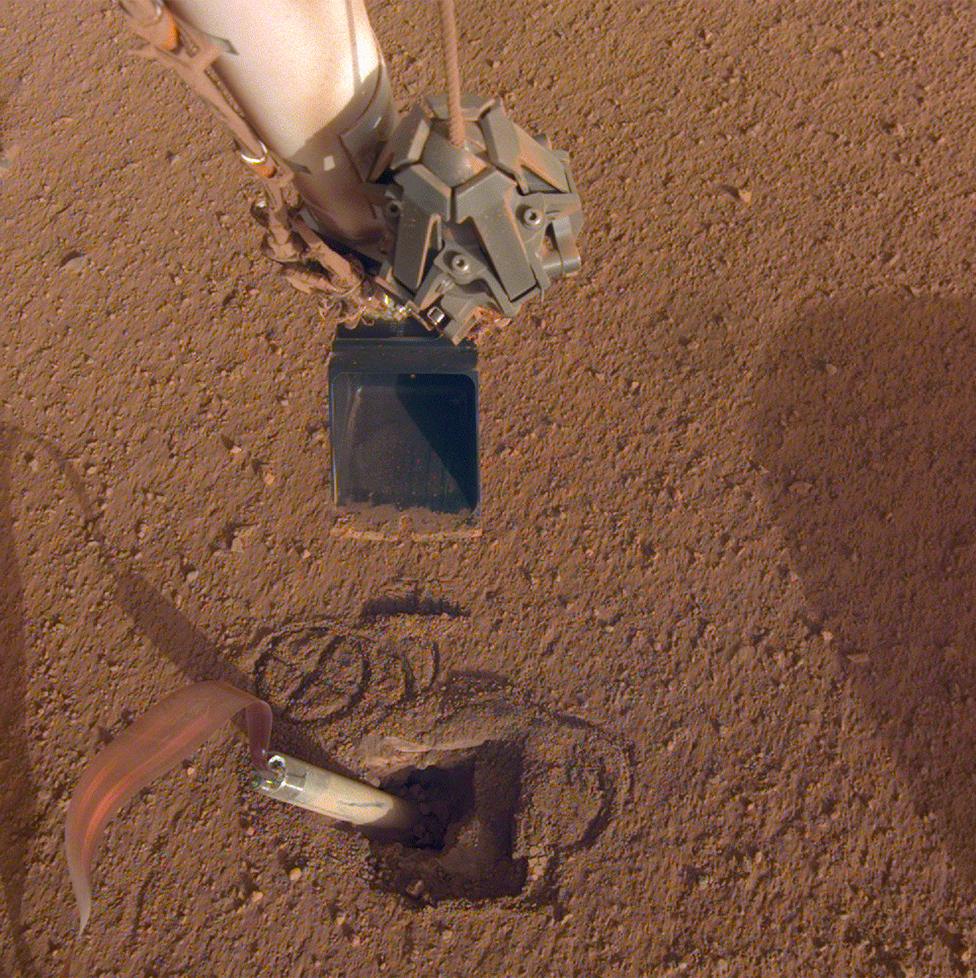

The heat flow "mole" has had difficulty burrowing into the ground

Indeed, to get a more resolved view of Mars' interior, the team could really do with detecting the Red Planet equivalent of a "Big One". Even just one very large event could make a big difference to the overall analysis.

Dr Banerdt said he remained hopeful: "It's the nature of statistics - sometimes things are clustered, sometimes there's large gaps in between. It's definitely not out of the question that we could see a couple of large quakes in the next few months."

InSight is currently financed by the US space agency to continue gathering data for another Earth year.

At the end of that period, it hopes also to have results from the radio experiment which should yield information on the size and density of the planet's core; and also from its heat-flow sensor. The latter is designed to burrow under the surface to measure the rate of Mars' heat loss but the hardware has had difficulty getting into position.

Engineers plan shortly to command InSight's robotic arm to push on the sensor to help it get underground.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external