Anak Krakatau: Lightning frenzy points to scale of volcanic plume

- Published

A phreatomagmatic eruption occurs when water comes into direct contact with magma

The 2018 eruption of Anak Krakatau in Indonesia was remarkable in many ways.

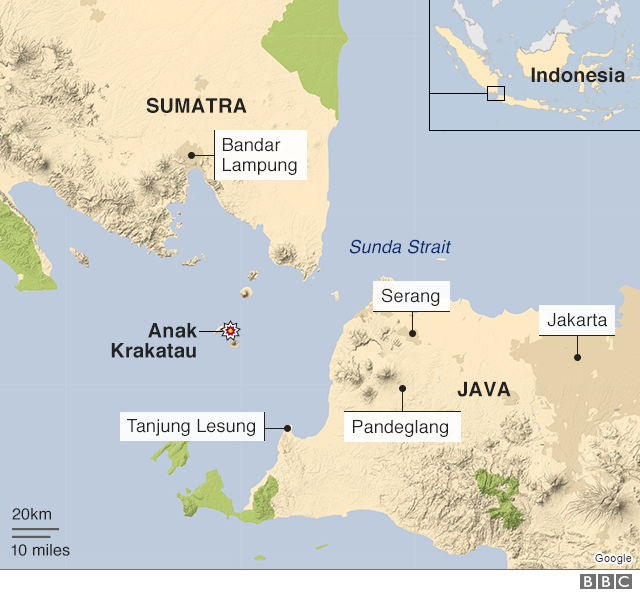

It will be remembered, obviously, for the sudden flank collapse that triggered the tsunami which killed over 400 people on the nearby coastlines of Sumatra and Java.

But the event also has been the source of many scientific insights that could inform future hazard assessments.

And a new possibility is the potential for the frequency of lightning seen at an eruption to give a simple guide to the height of a volcano's towering plume.

It's information that could be of interest to airlines trying to find safe routes for their planes.

Anak Krakatau had a huge eruption cloud that climbed 16-18km into the sky and which then levelled out into the classic anvil shape familiar from meteorological thunderstorms in the tropics.

Driving this tall convection column was the particular circumstances of the eruption.

When the wall of the volcano failed, it allowed seawater to come into direct contact with magma.

The result was a series of spectacular explosions that sent steam and ash rushing upwards.

Satellite observations indicate the "wet ash" fell back relatively quickly, but that much of the water vapour continued skyward, where it formed the anvil-topped plume that persisted for six days.

And, of course, as the water went higher and higher it eventually turned to ice in the sub-zero temperatures at altitude.

Using lightning to better understand eruptions is an emerging technique

Dr Andrew Prata, from the Barcelona Supercomputing Center in Spain, and colleagues have calculated the mass of all this ice - and the numbers involved are really quite impressive.

On average, there was three million tonnes hanging above Anak Krakatau. Up to 10 millions tonnes at the peak of ice production.

What's more, the movement through the plume of all this frozen material - some of it going up, some coming down - appears to have initiated a frenzy of lightning.

Approximately 100,000 strikes were recorded by sensors in those six days following the onset of the explosive phase of the eruption.

Over 70 flashes per minute at one point, says Dr Prata, whose team has just published its findings in the journal Scientific Reports, external.

"And what was interesting about that is that we started to see a relationship between the flash rate in the eruption plume and the height of the plume," he told BBC News.

"So, essentially, the greater the flash rate, the higher the plume. This is something that could be important and useful for aviation."

Anak Krakatau (centre island) lost its western flank on 22 December 2018

Planes need to be wary of flying through or near the eruption columns of volcanoes because of the damage fine ash can do to jet engines.

Airliners have experienced "flame-outs" in flight after their engines have ingested too much ash.

Dr Rebecca Williams from Hull University, UK, has been conducting her own research into the Anak Krakatau event.

She described the Spanish-led study as "fascinating", and agreed that it could assist volcano monitoring.

"Using lightning to detect volcanic eruptions is an emerging technique," she said.

"This study is a very important contribution to this - it correlates volcanic lightning data with volcanic cloud height in an ash-poor, ice-rich plume.

"This will be important in monitoring volcanic eruptions, particularly in remote areas which may impact aviation routes."

You might also be interested in:

Philippines' Taal volcano: Residents return to devastated homes

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external