Wasp-76b: The exotic inferno planet where it 'rains iron'

- Published

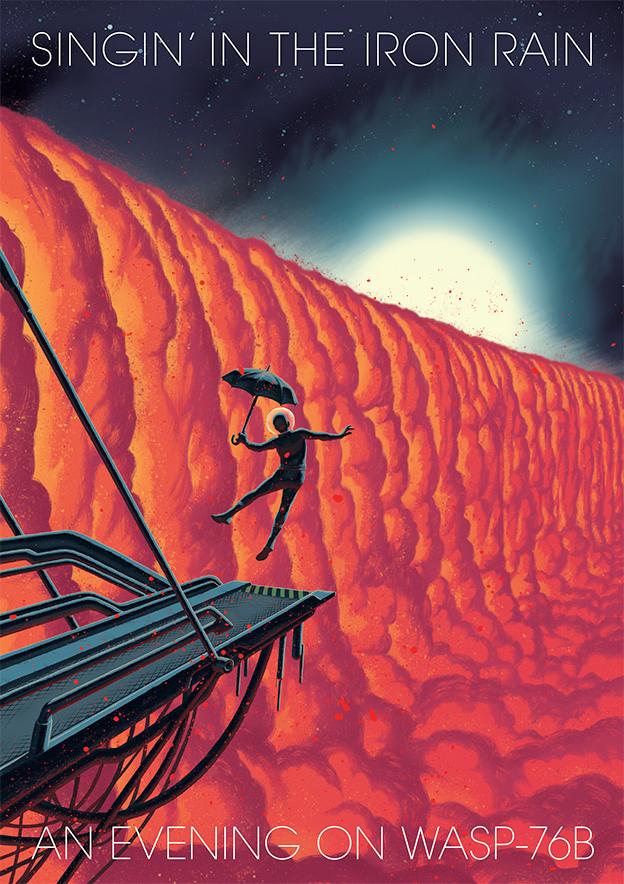

Artwork: The nightside would be hot, but cool enough for iron droplets to rain out

Astronomers have observed a distant planet where it probably rains iron.

It sounds like a science fiction movie, but this is the nature of some of the extreme worlds we're now discovering.

Wasp-76b, as it's known, orbits so close in to its host star, its dayside temperatures exceed 2,400C - hot enough to vaporise metals.

The planet's nightside, on the other hand, is 1,000 degrees cooler, allowing those metals to condense and rain out.

It's a bizarre environment, according to Dr David Ehrenreich from the University of Geneva.

"Imagine instead of a drizzle of water droplets, you have iron droplets splashing down," he told BBC News.

The Swiss researcher and colleagues have just published their findings on this strange place in the journal Nature, external.

The team describes how it used the new Espresso instrument, external at the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile to study the chemistry of Wasp-76b in fine detail.

Espresso is a new spectrometer attached to Europe's Very Large Telescope facility

The planet, which is 640 light-years from us, is so close to its star it takes just 43 hours to complete one revolution.

Another of the planet's interesting features is that it always presents the same face to the star - a behaviour scientists call being "tidally locked". Earth's Moon does exactly the same thing; we only ever see one side.

This means, of course, the permanent dayside of Wasp-76b is being roasted.

In fact, this hemisphere must be so hot that all clouds are dispersed, and all molecules in the atmosphere are broken apart into individual atoms.

What's more, the extreme temperature difference this produces between the lit and unlit portions of the planet will be driving ferocious winds, up to 18,000km/h says Dr Ehrenreich's team.

Using the Espresso spectrometer, the scientists detected a strong iron vapour signature at the evening frontier, or terminator, where the day on Wasp-76b transitions to night. But when the group observed the morning transition, the iron signal was gone.

"What we surmise is that the iron is condensing on the nightside, which, although still hot at 1,400C, is cold enough that iron can condense as clouds, as rain, possibly as droplets. These could then fall into the deeper layers of the atmosphere which we can't access with our instrument," Dr Ehrenreich explained.

Graphic novelist Frederik Peeters is known for his science fiction works

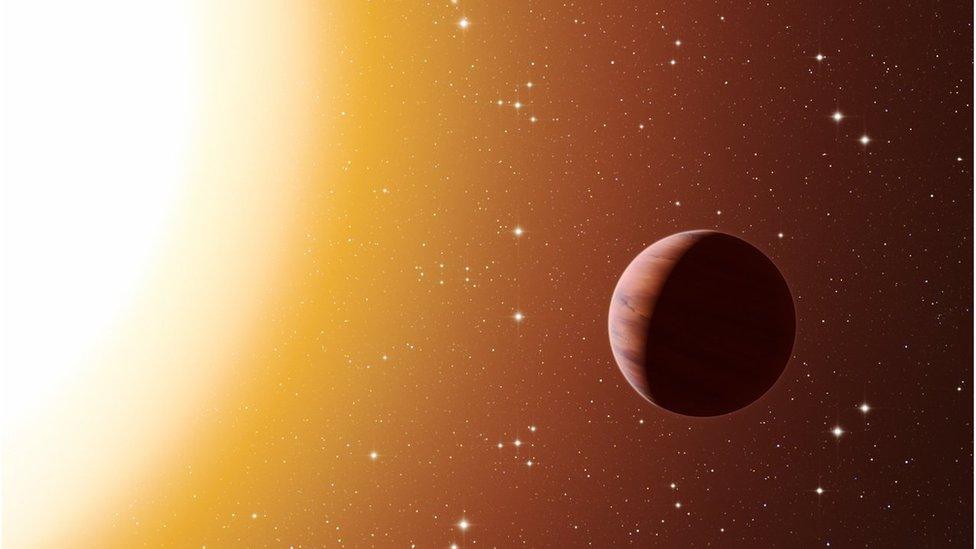

Wasp-76b is a monster gas planet that's twice the width of our Jupiter. Its unusual name comes from the UK-led Wasp telescope system, external that detected the world four years ago.

One of the scientists on the discovery team, Prof Don Pollacco from Warwick University, said it was hard to envisage such exotic worlds.

"This thing orbits so close to its star, it's essentially dancing in the outer atmosphere of that star and being subjected to all kinds of physics that, to put it bluntly, we don't really understand," he told BBC News.

"It will either end up in the star or the radiation field from the star will blow away the planet's atmosphere to leave just a hot, rocky core."

Dr Ehrenreich is a fan of graphic novels and asked the Swiss illustrator Frederik Peeters to produce an interpretation of Wasp-76b.

"Often with these discoveries, we see detailed 3D compositions where it's difficult for people to tell whether it's a real picture or just a computer-generated image. By putting some fun into it, we're not fooling anyone," he said.

Artwork: Wasp-76b is a "hot Jupiter". It's a gas giant like our Jupiter but orbits very close to its star

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external