Whale sharks: Atomic tests solve age puzzle of world's largest fish

- Published

Researcher Mark Meekan diving with a whale shark

Data from atomic bomb tests conducted during the Cold War have helped scientists accurately age the world's biggest fish.

Whale sharks are large, slow moving and docile creatures that mainly inhabit tropical waters.

They are long-lived but scientists have struggled to work out the exact ages of these endangered creatures.

But using the world's radioactive legacy they now have a workable method that can help the species survival.

Whale sharks are both the biggest fish and the biggest sharks in existence.

Growing up to 18m in length, and weighing on average of about 20 tonnes, their distinctive white spotted colouration makes them easily recognisable.

A whale shark foraging for plankton

These filter feeders live on plankton and travel long distances to find food.

They are very popular with tourists in many locations, often allowing divers to swim alongside them.

However, the species is now classified as endangered because of over-fishing in places like Thailand and the Philippines.

Much about the species remains a mystery, especially how to age them correctly.

Researchers say this is fundamental to understanding their growth rates - information that's considered crucial to saving the species in the long term.

Whale sharks are a big draw for tourists and generally pose little threat

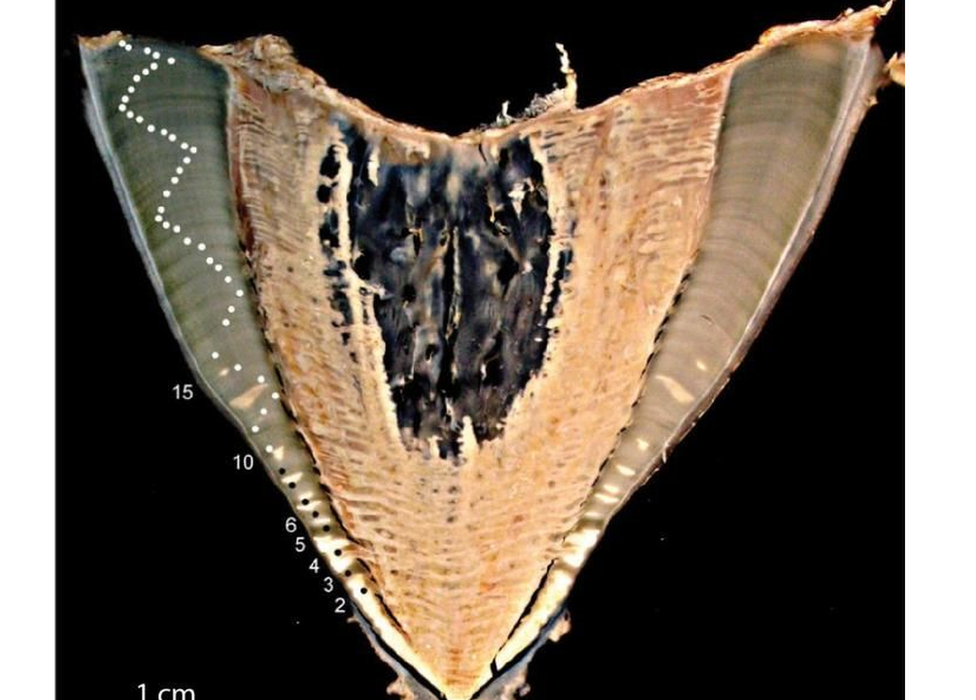

To date, scientists have tried to count distinct lines in the vertebrae of dead whale sharks. These act like rings in a tree trunk, increasing as the animal gets older.

But scientists have been unsure about how often these rings can form and the reasons behind them.

Now researchers say they have come up with a much more accurate way of determining the whale sharks' true age.

From the late 1940s, several nations including the US, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, France and China conducted atomic bomb tests in different locations.

A child plays with a dead whale shark, caught by fishermen off Indonesia

One side effect of all these explosions was the doubling of an atom type, or isotope, called Carbon-14 in the atmosphere.

Over time, every living thing on the planet has absorbed this extra Carbon-14 which still persists.

But as scientists know the rate at which this isotope decays, it is a very useful marker in determining age.

The older the creature, the less Carbon-14 you'd expect to find.

"So any animal that was alive then incorporated that spike in Carbon-14 into their hard parts," said author Dr Mark Meekan, from the Australian Institute of Marine Science in Perth.

"That means we've got a time marker within the vertebrae that means we can work out the periodicity at which those isotopes decay."

One of the difficulties with ageing these sharks has been in getting access to samples of vertebrae.

A cross section of a whale shark vertebra showing the growth bands

This team managed to find two long-dead specimens stored in Pakistan and Taiwan.

The study indicated that these creatures do actually live an incredibly long time.

"The absolute longevity of these animals could be very, very old, possibly as much as 100-150 years old," said Dr Meekan.

"This has huge implications for the species. It suggests that these things are probably intensely vulnerable to over-harvesting."

The scientists say their results explain why whale shark numbers have collapsed in locations like Thailand and Taiwan where fishing has taken place.

"They are just not built for humans to exploit," said Dr Meekan.

While the species has recently been upgraded from threatened to endangered on the IUCN Red List, the scientists believe that their work will help efforts at conservation.

By being able to accurately estimate the age of whale sharks, the scientists will be able to provide more accurate guidance on how well a population is doing and whether any fishing can be allowed.

In many tropical regions, whale shark tourism is now a major attraction. The researchers say that encouraging co-operation between different countries along the vast routes that whale sharks follow is key to their survival.

"Whale sharks are a fantastic ambassador for marine life and one that has lifted so many people out of poverty," added Dr Meekan.

"This is a good news story - and it shows there is a silver lining to the mushroom cloud after all," he quipped.

The study has been published, external in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external