Climate change: Blue skies pushed Greenland 'into the red'

- Published

Melting in Greenland in 2019

While high temperatures were critical to the melting seen in Greenland last year, scientists say that clear blue skies also played a key role.

In a study, they found that a record number of cloud free days saw more sunlight hit the surface while snowfall was also reduced.

These conditions were due to wobbles in the fast moving jet stream air current that also trapped heat over Europe.

As a result, Greenland's ice sheet lost an estimated 600 billion tonnes.

Current climate models don't include the impact of the wandering jet stream say the authors, and may be underestimating the impact of warming.

Greenland's ice sheet is seven times the area of the UK and up to 2-3km thick in places. It stores so much frozen water that if the whole thing melted, it would raise sea levels worldwide by up to 7m.

Last December, researchers reported that the Greenland ice sheet was melting seven times faster than it had been during the 1990s.

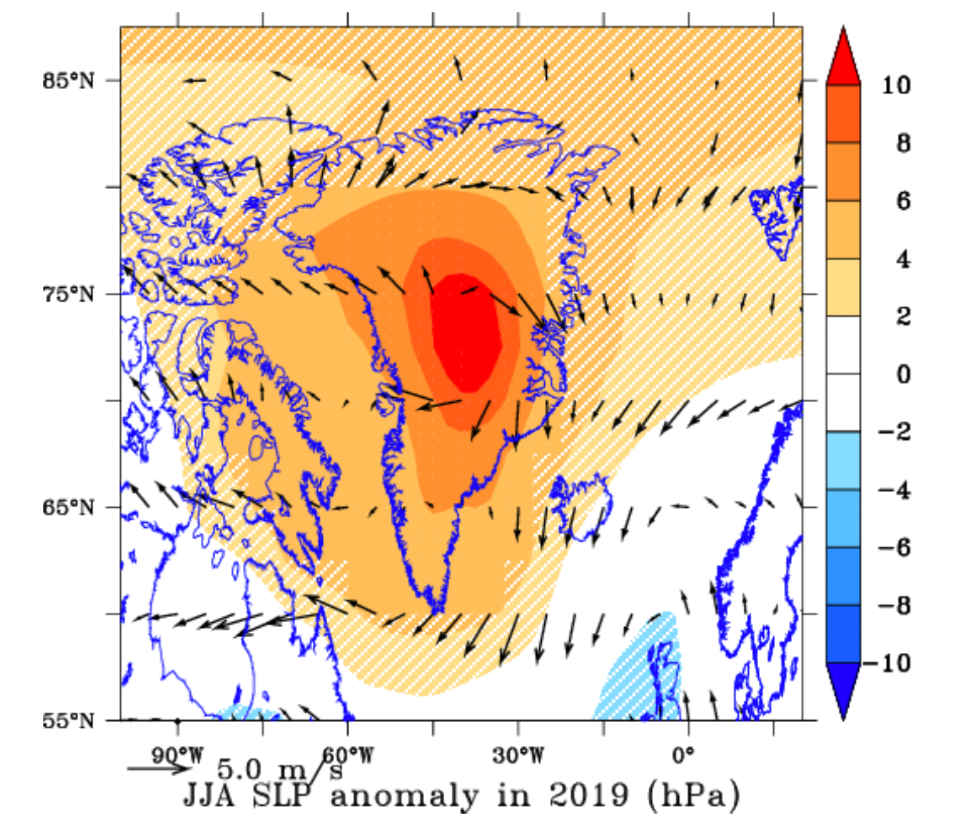

Average pressure over Greenland in summer 2019, with arrows showing wind direction

In recent weeks, an analysis of last year's melting said the 600 billion tonnes of ice added 2.2mm to global sea levels in just two months.

This new study says that while rising global temperatures played a role in the events last year, changes in atmospheric circulation patterns were also to blame.

Researchers found that high pressure weather conditions prevailed over Greenland for record amounts of time.

They believe this is connected to what's termed the "waviness" in the jet stream, the giant current of air that mostly flows from west to east around the globe.

As the current becomes more wobbly, it bends north, and high pressure systems that would normally move through in a few days become "blocked' over Greenland.

These systems had different impacts depending on the part of Greenland you were in.

In the southern part of the island, the authors say, it caused clearer skies with more sunlight hitting the surface.

The cloud-free days brought less snow, which meant that 50 billion fewer tonnes were added to the ice sheet.

The absence of snow also exposed bare, dark ice in some place which absorbed more heat - contributing to the melt.

In other parts of Greenland, the changing atmospheric patterns had different but equally damaging impacts.

In northern and western region, the swirling but stuck high pressure systems pulled in warm air from southern latitudes.

"You can imagine that a sort of vacuum cleaner that is spinning clockwise and sucking all the warm and moist air from New York City for example," said lead author Dr Marco Tedesco from Columbia University in New York, US.

"And because of the rotation, it deposits this warm, moist air high in the northern part. It forms clouds, and they behave like a greenhouse, trapping the heat that would normally radiate off the ice."

Dr Tedesco explained that Greenland in 2019 experienced the largest drop in surface mass balance since records began in 1948.

The term surface mass balance describes the overall state of the ice sheet after accounting for gains from snowfall and losses from surface melt-water run-off.

The authors believe their study explains why, despite the fact that 2019 was not as warm as 2012, last year produced a record drop in surface mass balance.

"This is really pushing Greenland into the red," said Dr Tedesco.

Other researchers working in this field agreed that the new paper is a good explanation of what happened last year in Greenland.

"The main message of the paper is that the very high melt was mostly driven by clear skies and direct melting rather than necessarily being attributable to unusually high temperatures over the ice sheet - a radiatively-driven, rather than thermally-driven, melt season as they put it," said Dr Ruth Mottram, a climate scientist at the Danish Meteorological Institute in Copenhagen.

"In some ways, the weather pattern is rather similar to the great blocking high that lodged over Scandinavia for weeks in 2018, giving us the most extreme drought on record in much of northern Europe."

Marco Tedesco (left) and a colleague measure reflectance on the Greenland ice sheet during a 2018 expedition

The exact mechanism by which climate change affects the jet stream isn't understood. But the view is that as the Arctic warms, the temperature differences between the region and the mid-latitudes that drive the air current are reduced. This slows down the stream, making it wander further.

"The more CO2 we pump out, the more divergence starts to emerge between the behaviour of the Arctic and the mid-latitudes and this behaviour is accelerating and enhancing some of the differences. It is a crucial part of what is creating this waviness and the consequences," said Dr Tedesco.

The authors also argue that climate models in general need to take account of this impact of the wavy jet stream. Others in the field say this issue needs addressing.

"These results imply that the climate models we use for future projections of sea level rise from Greenland are underestimating the extreme years at present and therefore likely also the rate at which the ice sheet melts and the oceans will rise in the future," said Dr Mottram.

"The only ray of light is that as processor power increases and we can do higher resolution simulations with climate models, the representation of these processes does seem to improve and not just in Greenland but in other areas of the world where persistent blocking patterns can have an important influence on the season."

The study has been published in the journal The Cryosphere, external.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external