Antarctic algal blooms: 'Green snow' mapped from space

- Published

The satellite observations were accompanied by measurements on the snow surface

UK scientists have created the first wide-area maps of microscopic algae growing in coastal Antarctica.

Satellite observations were used to count nearly 1,700 patches where large blooms had turned snow cover green.

The team says the photosynthesising organisms are an important "sink" for pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

They are also key actors in the cycling of nutrients in what is one the most remote regions on Earth.

"These are primary producers at the bottom of a food chain. If there are changes in the algae, it obviously has knock-on effects further up the food chain," explained study leader Dr Matt Davey from Cambridge University.

"And even though the numbers we're talking about are small on a global scale, on an Antarctic scale they're substantially important," the ecologist, who has since joined the Scottish Association for Marine Science in Oban, told BBC News.

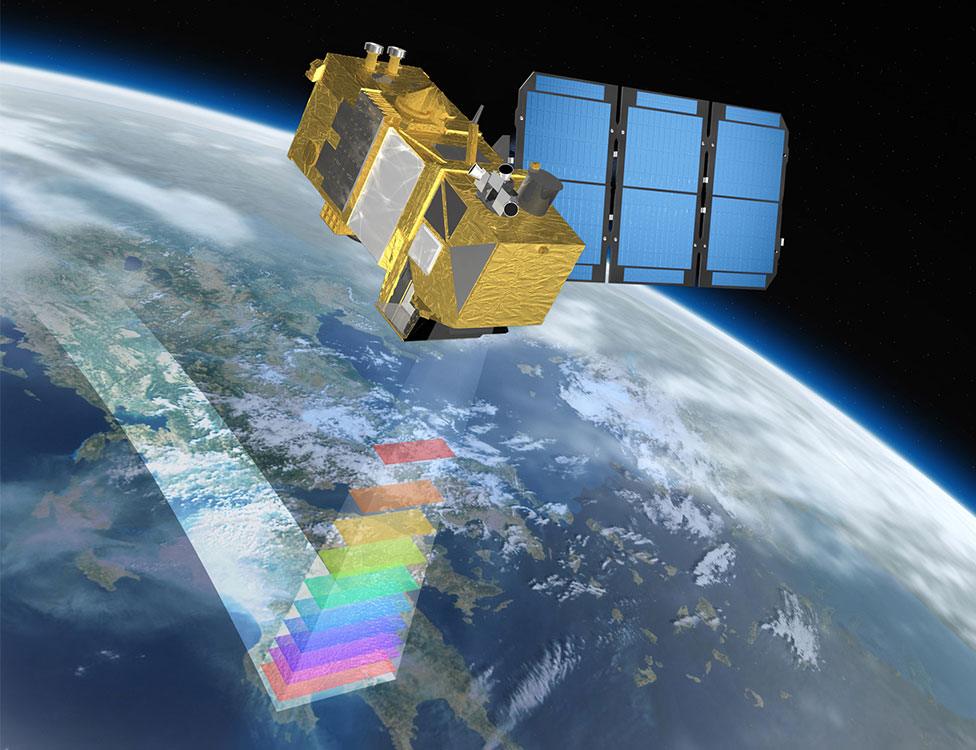

Artwork: Sentinel-2 is owned by the EU and managed by the European Space Agency

Detecting the green algae from space was a tricky task.

While it's easy to spot the organisms' discolouration when walking in the snow on the ground, from orbit it becomes much harder to tease out the blooms' signal against what is a highly reflective surface.

Fortunately for the team, the European Union's Sentinel-2 spacecraft have high-fidelity detectors that are sensitive in just the right part of the light spectrum to make the observation.

The study mapped the Antarctic Peninsula, the finger of land which points up from the White Continent towards South America. The blooms are seen predominantly to be on the western side of this feature. Two-thirds were on the many islands that dot the coastline.

Totalled, the microscopic algae covered an area of almost 2 sq km. It means they're tying up roughly 500 tonnes of carbon a year. This is equivalent to the amount of carbon that would be emitted by about 875,000 average petrol car journeys in the UK, the team calculates.

The algae bloom in "warmer" areas. They need access to liquid water

These numbers are an underestimate because the Sentinel-2 system is only picking up green algae and missing their red and orange counterparts - an issue of the satellite camera detectors' spectral bands not being sensitive at just the right wavelengths for those particular blooms.

"It's frustrating because we've shown how to do it on the WorldView-3 spacecraft but its imagery is just too expensive. Sentinel is free," explained Dr Andrew Gray, who is affiliated to both Cambridge and the NERC Field Spectroscopy Facility in Edinburgh.

The problem would be resolved in time as more open-data satellites were launched, the remote-sensing specialist added.

Algal blooms in the Antarctic were first described by expeditions in the 1950s and 1960s. They can look spectacular when they tinge slopes with a broad swathe of colour to contrast the surrounding white. This makes them a popular subject for cruise ship tourists and their cameras.

To flourish, the organisms need an available supply of liquid water and that's to be found in snowy areas just above freezing, as opposed to those places of deep cold and ice.

The blooms' distribution is also heavily influenced by the proximity of seals, penguins and other Antarctic birds, such as skuas and kelp gulls. The "poop" from these creatures is a source of essential nitrogen and other elements.

The interesting question is what happens to the blooms as the Antarctic warms. Temperatures on the peninsula rose rapidly in the latter half of the 20th Century, and climate models expect this trend to continue in coming decades.

Many of the algal fields on low-lying islands could simply disappear if their snows are completely removed. On the other hand, new opportunities are likely to open up on the mainland, further to the south and at higher elevations.

"There are probably many different species of algae, all with quite different niches. Some will live right at the top of the snow surface, others quite a bit deeper - and their numbers will change depending on the temperature," observed Prof Alison Smith, a biologist at Cambridge.

"But we don't know yet whether their numbers will increase or decrease. And if you don't monitor the situation, you'll never know," she told BBC News.

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, external, involved additional team-members from the British Antarctic Survey and Edinburgh University.

Jonathan.Amos-INTERNET@bbc.co.uk, external and follow me on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external