What the heroin industry can teach us about solar power

- Published

If you have ever doubted whether solar power can be a transformative technology, read on.

This is a story about how it has proved its worth in the toughest environment possible.

The market I'm talking about is perhaps the purest example of capitalism on the planet.

There are no subsidies here. Nobody is thinking about climate change - or any other ethical consideration, for that matter.

This is about small-scale entrepreneurs trying to make a profit.

It is the story of how Afghan opium growers have switched to solar power, and significantly increased the world supply of heroin.

Black Hawk over Helmand

I was in a military helicopter thundering over the lush poppy fields of the Helmand valley in Afghanistan when I spotted the first solar panel.

You've heard of Helmand. It is the most dangerous province in Afghanistan.

Of the 454 British soldiers who died in the recent conflict in Afghanistan, all but five lost their lives in Helmand.

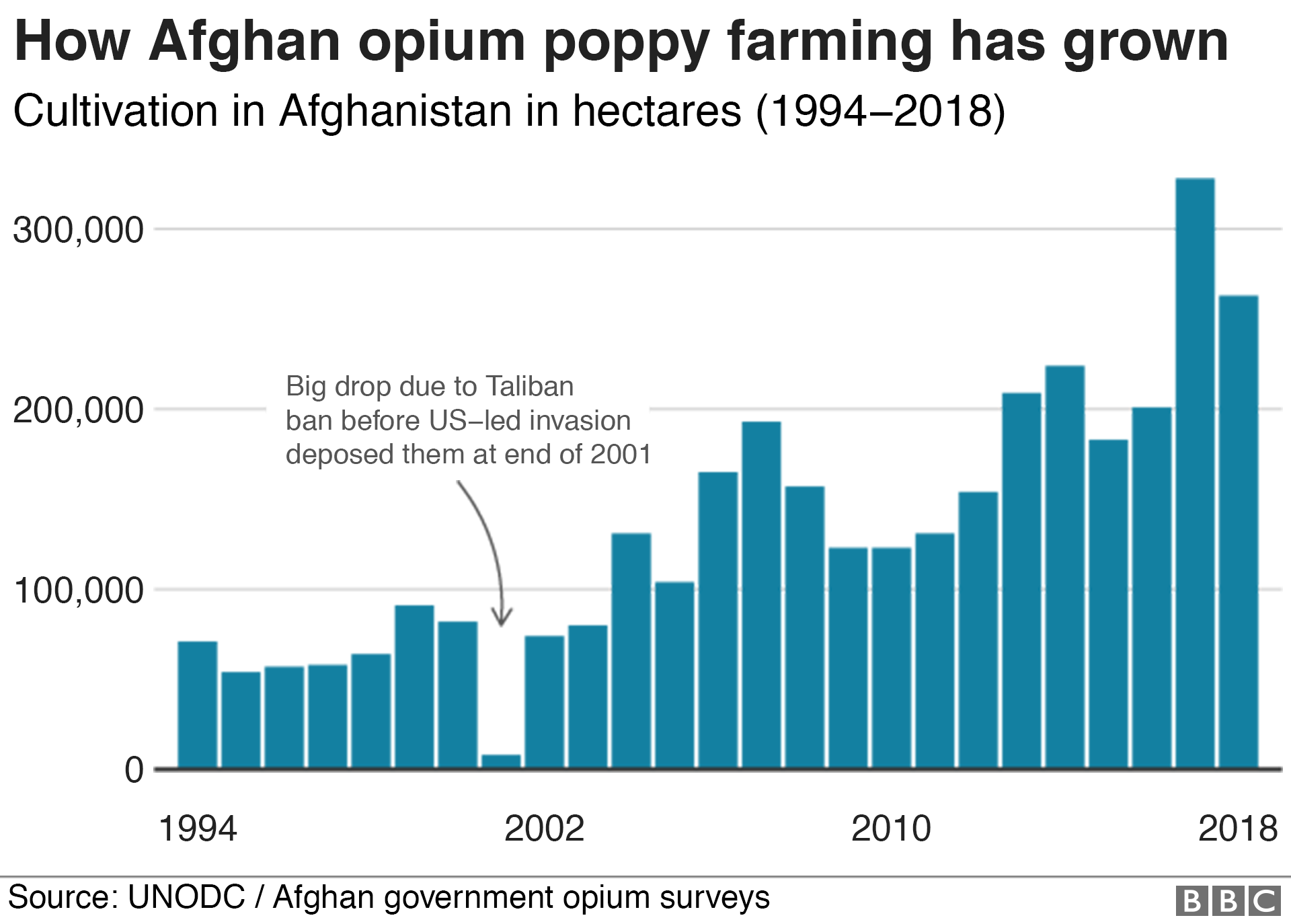

The province is also at the heart of by far the most productive opium-growing region on the planet.

Most opium will be refined into heroin, one of the most addictive drugs there is.

According to the UN body responsible for tracking and tackling illegal drug production, the UNODC, almost 80% of all Afghan opium now comes from the south-west of the country, including Helmand.

That means pretty much two-thirds of global supply.

So, not the kind of place you would expect to be at the forefront of efforts to decarbonise the economy.

But, once I had seen that first solar panel, I saw more.

In fact there seemed to be a small array of solar panels in the corner of most farm compounds, and that was back in 2016.

It is only now that the scale of the revolution in heroin production I was unwittingly witnessing has been quantified.

Because I wasn't the only person to notice that Afghan farmers were taking an interest in low-carbon technologies.

Evidence from space

Richard Brittan is hunched over his computer in a nondescript office on an industrial estate just outside Guildford, in the south of England.

He is reviewing the latest cache of satellite images from Afghanistan.

Mr Brittan is a former British soldier whose company, Alcis, specialises in satellite analysis, external of what he calls "complex environments".

That's a euphemism for dangerous places. Among other things, Mr Brittan is an expert on the drugs industry in Afghanistan.

He zooms in on an area way out in the deserts of Helmand.

A few years ago there was nothing here. Now there is a farm surrounded by fields.

Zoom in a bit more and you can clearly see an array of solar panels and a large reservoir.

Over to the right a bit there is another farm. The pattern is the same: solar panels and a reservoir.

A zoomed-in satellite image shows the banks of solar panels in a farm in the Helmand river valley

We scroll along the image and it is repeated again and again and again across the entire region.

"It's just how opium poppy is farmed now," Mr Brittan tells me. "They drill down 100m (325ft) or so to the ground water, put in an electric pump and wire it up to a few panels and bingo, the water starts flowing."

Take-up of this new technology was very rapid.

The first report of an Afghan farmer using solar power came back in 2013.

The following year traders were stocking a few solar panels in Lashkar Gah, the Helmandi capital.

Since then growth has been exponential. The number of solar panels installed on farms has doubled every year.

By 2019 Mr Brittan's team had counted 67,000 solar arrays just in the Helmand valley.

In Lashkar Gah market, solar panels are now stacked in great piles three storeys high.

It is easy to understand why trade has been so brisk.

Solar has transformed the productivity of farms in the region.

I've got a video shot a couple of weeks ago on an opium farm in what used to be desert.

The farmer shows us his two arrays of 18 solar panels. They power the two electric pumps he uses to fill a large reservoir.

He films the small canal that allows him to use the water to irrigate his land. All around, his fields seem to be flourishing.

He harvested his opium crop in May; now he is growing tomatoes.

"Solar has changed everything for these farmers," says Dr David Mansfield as we watch the video.

Dr Mansfield is the author of the report, external. He has been studying opium production in Afghanistan for more than 25 years and tells me the introduction of solar is by far the most significant technological change he has seen in that time.

Buying diesel to power their ground water pumps used to be the farmers' biggest expense.

"And it isn't just the cost," Dr Mansfield continues. "The diesel in these remote areas is heavily adulterated so pumps and generators keep breaking down. That's a huge problem for farmers."

Now it is very different.

For an upfront payment of $5,000 they can buy an array of solar panels and an electric pump. Once it is installed, there are virtually no running costs.

Once the equipment is bought, water is free

It is a lot of money, he concedes - the average dowry is $7,000 - but the boost to productivity is enormous and any loan is usually paid back within a couple of years.

"From then on, water is effectively free," he says.

It means they can grow far more poppy - as well as other crops.

Many farms now get two harvests a year - some even get three.

And that's not the only breakthrough. Using solar also means farmers can grow poppy in places where they never would have considered farming before.

Into the desert

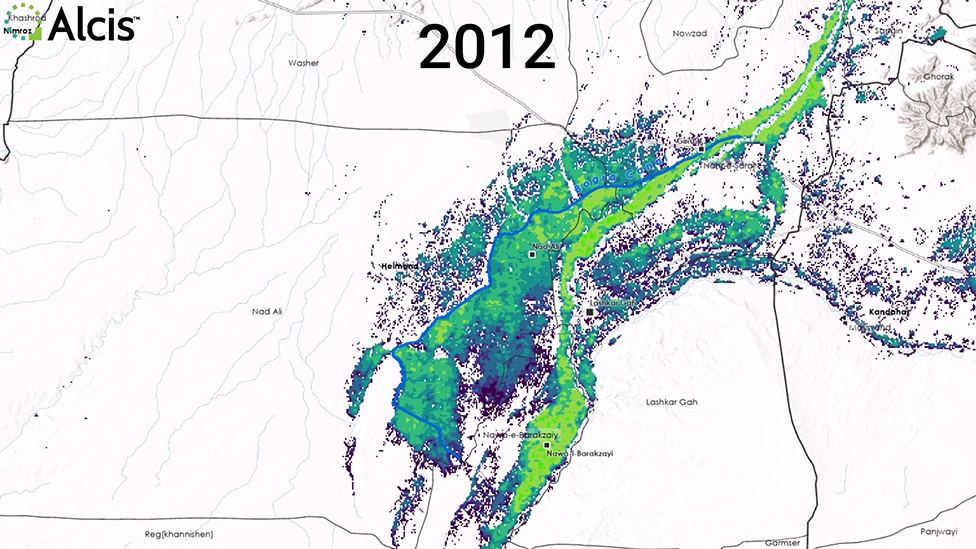

Back in his office in Guildford, Richard Brittan calls up a new screen on his computer.

It shows the entire Helmand valley.

He superimposes an image showing the area under cultivation in 2012.

Then, farmers were working 157,000 hectares.

A series of images show how this changed over time.

You can see the farms spreading out into the desert as farmers start using solar.

It looks like a fungus growing. But this is on a huge scale.

The area under cultivation has been increasing by tens of thousands of hectares every year.

By 2018 it had doubled to 317,000 hectares.

In 2019 it was 344,000 hectares.

"And it is continuing to grow," he says.

At the same time, the land is getting more productive.

His maps are shaded from dark purple - poor yields - through to light green, which indicates the most productive land.

As farmers switch to solar, you can see the area shaded green growing.

"All this water is making the desert bloom," Mr Brittan says.

And as the area under cultivation has grown, so has the number of people.

Mr Brittan estimates half a million people have migrated into the desert areas of Helmand in just the last five years.

His team has counted an additional 48,000 homes built in the same period.

And the impact on the world supply of opium appears to have been equally dramatic.

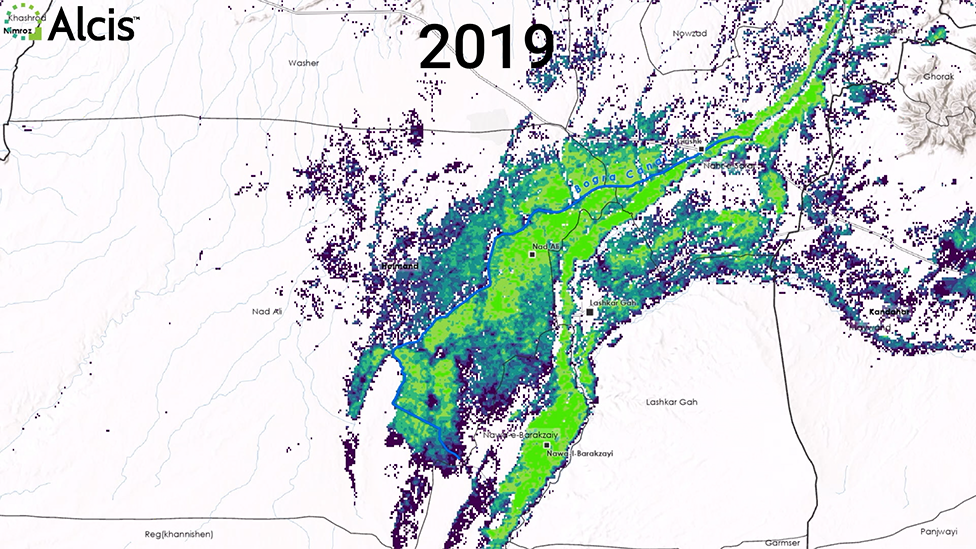

Every year the UN estimates the quantity of illegal drugs being produced around the world.

In 2012 - before solar - it calculated that Afghanistan produced a total of 3,700 tonnes of opium.

By 2016 production had grown to 4,800 tonnes.

In 2017 there is a truly bumper harvest, by far the biggest Afghanistan has ever produced - 9,000 tonnes of opium.

So much opium that prices crashed.

What happened next is very interesting.

In 2018 and 2019 the area of poppy cultivated in most of Afghanistan fell, except in the south west, where farmers have made this big investment in solar technology.

Here opium production actually increased.

In 2019 opium production in the region reached almost 5,000 tonnes - out of the 6,400 tonnes the whole country produced.

The effects of this unprecedented productivity have been felt around the world.

A pyramid scheme for doing good

In September UK police seized 1.3 tonnes of heroin worth an estimated £120m, the country's largest ever seizure.

No surprise then that The Well, Dave Higham's addiction recovery charity in the north-west of England, is thriving.

Mr Higham's approach to tackling addiction is based on the Hollywood movie Pay it Forward.

The idea is you don't pay favours back - instead, you return big favours by helping out people you don't know.

It is basically a pyramid selling scheme but for doing good, and it seems to be working.

The Hub in Barrow-in-Furness, one of The Well's network of buildings in the region, is buzzing with people.

Everyone is either an addict or a former addict "paying forward".

Former addict Dave Higham now runs a charity for recovering addicts

Mr Higham was a heroin addict for 25 years and says he has noticed subtle signs of an increase in the supply of heroin in recent years.

The addicts he works with say the quality of the heroin they buy is improving and there don't seem to be the droughts in supply that Mr Higham says he regularly experienced during his quarter century of addiction.

Most of his clients are part of the estimated 260,000 to 300,000 long-term heroin users in the UK.

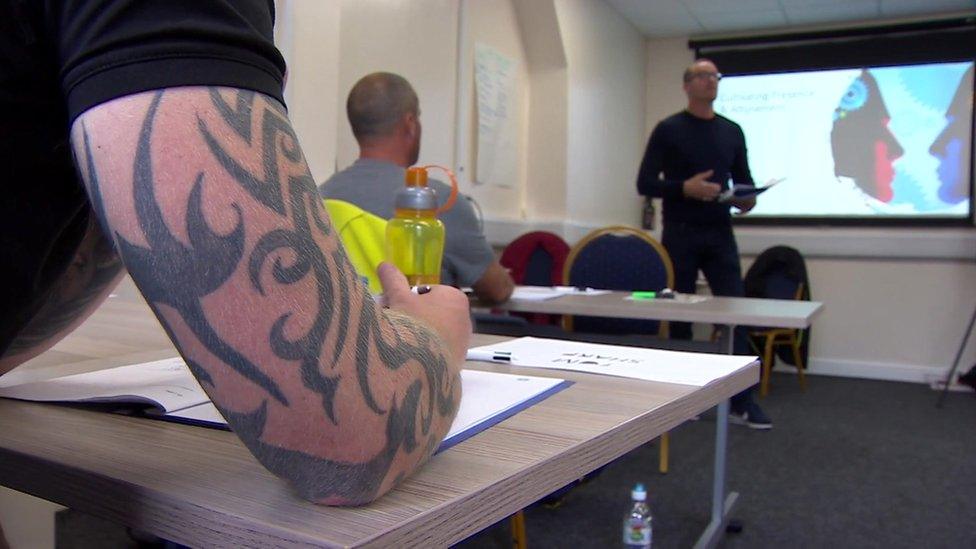

One of the classes at The Well

But he says he has started to see what he calls "new generation" of addicts coming in for help.

Mr Higham, like many older addicts, developed his habit in the 1980s, when unemployment topped three million and high-quality Afghan heroin had just started to arrive in the UK.

Like many drugs workers across the country, his big fear is that a deep post-Covid recession with prolonged mass unemployment will coincide with these bumper solar-powered supplies of Afghan heroin.

If that happens, he warns, you can expect crime rates to soar, because most addicts have to steal to fund their habits.

I've travelled all over the world for the BBC and seen evidence of environmental damage and climate change everywhere. It's the biggest challenge humanity has ever faced. Tackling it means changing how we do virtually everything. We are right to be anxious and afraid at the prospect, but I reckon we should also see this as a thrilling story of exploration, and I'm delighted to have been given the chance of a ringside seat as chief environment correspondent.

What does this tell us about solar power?

That is simple.

The story of the revolution in Afghan heroin production shows us just how transformative solar power can be.

Don't imagine this is some kind of benign "green" technology.

Solar is getting so cheap that it is capable of changing the way we do things in fundamental ways and with consequences that can affect the entire world.

A team of engineers trekked into the Himalayas to bring a community electricity

In many markets, solar is already cheaper than fossil fuels.

What's more, its cost follows the logic of all manufacturing - the more you produce and install, the cheaper it gets.

That means we can expect a lot more of the power we all use to be generated from solar energy in the years to come.

And what the changes in Afghan opium production show us is that having a source of power independent of any electricity grid - or fossil fuel supplies - can bring significant innovation.

It also proves the consequences won't always be positive.

That is true for the Afghan farmers as well as heroin addicts.

So much water is now being used that ground water levels in Helmand are estimated to be falling by 3m a year.

The fear is that pretty soon the water will simply run out.

"Maybe this boom will not last longer than 10 years," says Orzala Nemat, who runs the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, the country's biggest think tank.

Orzala Nemat is worried the water will run out

That won't just affect the people who have moved into the desert areas, she says. It will affect the entire region.

More than 1.5 million people could be forced to migrate.

Some will move to other areas of Afghanistan, she believes, but many will try to leave the country and travel to Europe and America where they believe their prospects will be better.

She has no doubts what this will mean.

"It is going to be a major crisis," she says.