UK to set limits on harmful airborne particles

- Published

A new target will be set to protect people from the effects of breathing in tiny particles produced by transport and industry, the UK government says.

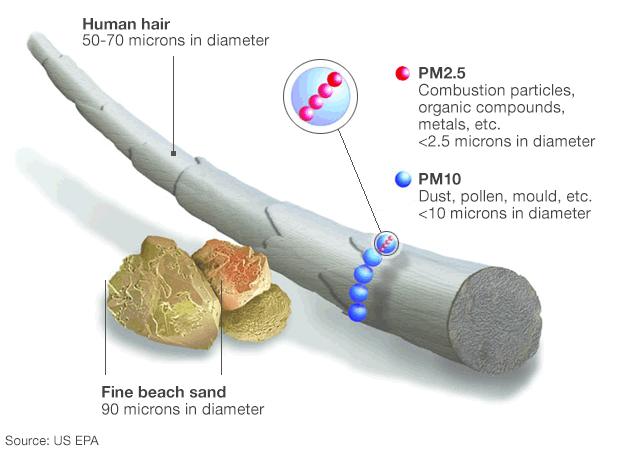

The country falls some way short of a limit recommended by the World Health Organization for tiny particles called PM 2.5s.

These are produced by burning fuels in power generation, domestic heating and in vehicle engines.

PM 2.5s are known to harm the lungs and heart.

Ministers will confirm a legally binding PM 2.5 target in two years' time, alongside goals for waste reduction, wildlife, and water.

The announcement follows criticism that the government's 2020 Environment Bill failed to include binding targets.

It’s had a mixed reception from green groups, who can't tell yet whether the planned targets will be strong or broad enough to tackle the current ecological crisis.

They’re also dismayed that the targets won’t be settled until 2022.

The government’s new goals will commit to restoring and creating wildlife-rich habitats in protected sites, as well as tackling pollution from agriculture and waste water to improve water quality.

Annual progress will be monitored by a new environmental watchdog, the Office for Environmental Protection.

It’s hoped that setting targets will have the same effect on the broader environment that they’ve had on cutting carbon emissions.

Environment Secretary George Eustice said: “The targets we set will be the driving force behind our bold action to protect and enhance our natural world - guaranteeing lasting progress on some of the biggest environmental issues.

"I hope these targets will provide some much-needed certainty to businesses and society."

The announcement has already generated debate about where the targets should be applied and how strong they should be.

Richard Benwell from Wildlife and Countryside Link, said: “These proposals show the government is considering a truly bold breadth of targets for Nature - well beyond the statutory minimum.

“Nevertheless, more ambition will be needed to turn round the relentless decline in our natural world.”

Air pollution: what are the effects on humans?

Emerging thinking in the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, for instance, suggests that around 30% of land and seas should be managed for nature by 2030 in order to reverse the declines of recent decades - the so called 30 by 30 target.

Joan Edwards, from the Wildlife Trusts conservation group, told BBC News: “Currently, around 8% of the land area of England is designated as a national or international protected area - and most of this is not being managed properly.

“The same's true for our seas - plenty of designated sites but they're still being fished and built upon.

“We need more of our land, water and seas managed for nature’s recovery."

There are calls for a new chapter in the Bill to address the nation’s “global footprint“ - the impact on the overseas environment from things consumed in the UK.

Protecting the Amazon

Kate Norgrove, from the wildlife campaign group WWF, said: “A credible Environment Bill must help protect the Amazon and other disappearing habitats with tough new nature laws to eliminate deforestation from the products we buy.”

Friends of the Earth has huge concerns over the timescale for action under the Bill.

Its campaigner Kierra Box said: “Ministers must also close a huge loophole that could allow action to be delayed for many years - currently the targets are not expected to be met until 2037 at the earliest.

“Governments have a dismal track record of missing and abandoning voluntary environmental goals, so Parliament must insist on giving interim targets binding legal status too.”

The plan has been proposed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), which is working in consultation with devolved authorities around the UK.

Follow Roger on Twitter., external