Climate change: 'Unprecedented' ice loss as Greenland breaks record

- Published

Scientists say the loss of ice in Greenland lurched forward again last year, breaking the previous record by 15%.

A new analysis, external says that the scale of the melt was "unprecedented" in records dating back to 1948.

High pressure systems that became blocked over Greenland last Summer were the immediate cause of the huge losses.

But the authors say ongoing emissions of carbon are pushing Greenland into an era of more extreme melting.

Over the past 30 years, Greenland's contribution to global sea levels has grown significantly as ice losses have increased.

A major international report on Greenland released last December concluded that it was losing ice seven times faster than it was during the 1990s.

Today's new study shows that trend is continuing.

Using data from the Grace and Grace-FO satellites, as well as climate models, the authors conclude that across the full year Greenland lost 532 gigatonnes of ice - a significant increase on 2012.

The researchers say the loss is the equivalent of adding 1.5mm to global mean sea levels, approximately 40% of the average rise in one year.

Climate scientist Steffen Olsen took this picture while travelling across melted sea-ice in north-west Greenland in 2019

According to a calculation by Danish climate scientist Martin Stendel, the 2019 losses would be enough to cover the entire UK with around 2.5 metres of melt water.

Both last year and 2012 were marked by "blocking" events, the researchers say, where disturbances in the jet stream saw high pressure systems become stuck over Greenland, resulting in enhanced melting.

"We seem to have entered a realm of more and more extreme melt in Greenland," said lead author Dr Ingo Sasgen, from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany.

"It's expected that something like the 2019 or 2012 years will be repeated. And we don't exactly know how the ice behaves in terms of feedback mechanisms in this vigorous range of melting."

"There could be... hidden feedbacks that we are not aware about or that are maybe not perfectly described in the models right now. That could lead to some surprises."

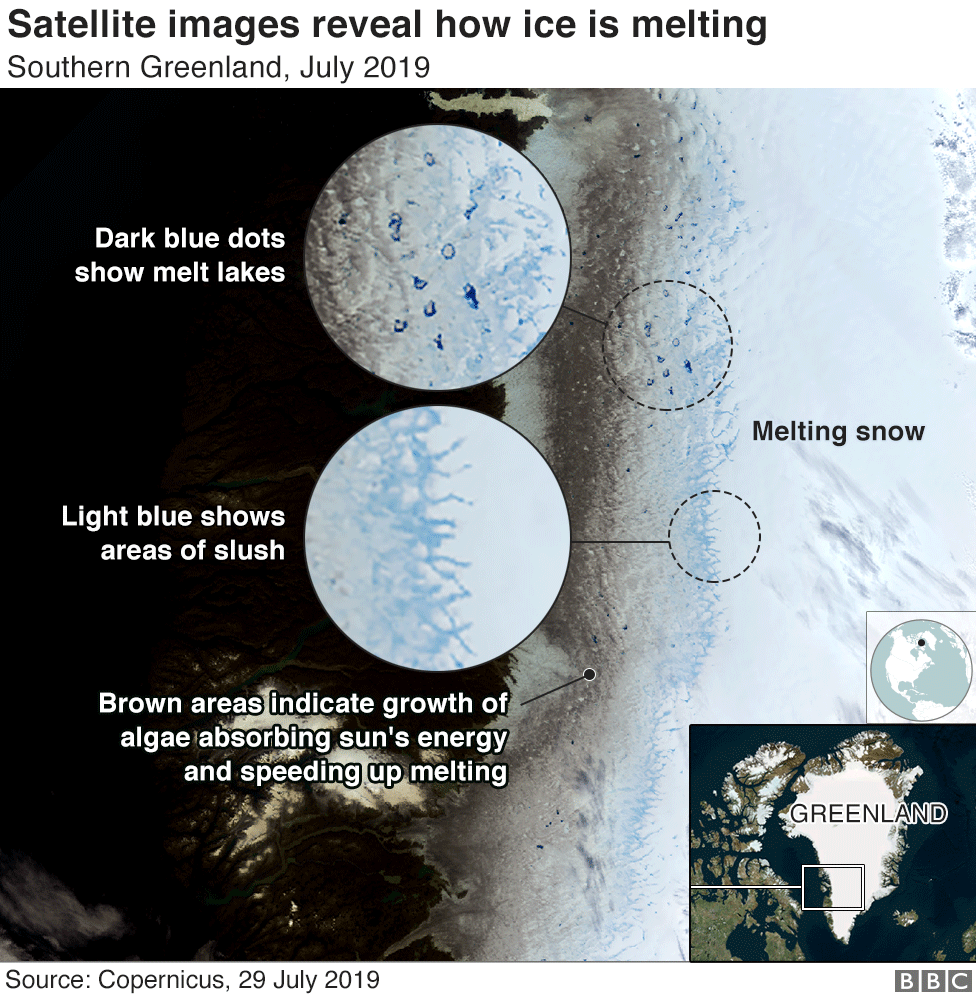

Ice loss from 1992 to 2018 has occurred mostly around the coast (Imbie/ESA/Planetary Visions)

While 2019 broke the record, both 2018 and 2017 saw decreased ice losses, lower than any other two-year period since 2003.

The authors say this was due to two very cold summers in Greenland followed by heavy snows in autumn.

However the return to high levels of melting in 2019 is a major concern. Five of the years with the biggest mass loss have now occurred in the past decade.

"What really matters is the trend," said Dr Ruth Mottram, from the Danish Meteorological Institute in Copenhagen, who wasn't involved with this new study.

"And that trend as shown through the Imbie (Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise) project and other work is tracking the high end of projections."

While 2020 has so far seen average conditions in Greenland, the overall impact of the massive ice losses seen in recent years could have major implications for people living in low lying areas of the world.

"The result for 2019 confirms that the ice sheet has returned to a state of high loss, in line with the IPCCs worst-case climate warming scenario," said Prof Andy Shepherd from Leeds University, who is the co-lead investigator for Imbie.

'This means we need to prepare for an extra 10cm or so of global sea level rise by 2100 from Greenland alone."

"And at the same time we have to invent a new worst-case climate warming scenario, because Greenland is already tracking the current one."

"If Greenland's ice losses continue on their current trajectory, an extra 25 million people could be flooded each year by the end of this century."

Recent media reports have suggested that Greenland may have passed a point of no return, that the level of global warming that the world is already committed to because of carbon emissions, means that all of Greenland will melt.

Dr Sasgen says that this perspective may be correct - but Greenland's fate is still in our hands.

"The rates of sea level rise we expect from Greenland, and the risk of sudden sea level rise from Greenland is drastically reduced if we stay below the warming limits," he said.

"The take home message is that if we reduce CO2, and we reduce or limit global warming, then also the risk for huge contributions from Greenland in the near future will also be reduced."

The paper has been published in the Nature journal Communications Earth & Environment, external.

Follow Matt on Twitter., external.