UK climate plan: What do the terms mean?

- Published

The UK prime minister is set to publish his long-awaited "net zero" plan to tackle climate change. He has already backed technologies like carbon capture and storage, hydrogen, and small reactors. Here, we break down some of the terms we're likely to hear about in the plan.

What is net zero?

The world is over-heating fast, thanks to emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases from burning fossil fuels.

Another important human-produced heating gas is methane – mostly from farming and landfill.

Scientists warn it simply won’t be possible to get emissions of these to zero by the UK's chosen date of 2050.

So instead, the government is aiming for a target known as net zero. That means the emissions that can’t be avoided by clean technology in 2050 will either be buried using the technology of carbon capture and storage, or soaked up by plants and soils.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS)

This does what it says on the tin – a technology that employs a chemical process to capture CO2 emissions from industrial chimneys. The gas is then compressed and forced into porous underground rocks.

Two decades ago, it was touted as a climate saviour. But it's very expensive and has never really taken off.

New technologies can also take waste CO2 and turn it into useful chemicals – but demand is vastly outstripped by the supply of unwanted CO2.

Net zero vs carbon neutral

Let's take net zero first. It refers to balancing out any greenhouse gas emissions produced by industry, transport or other sources by removing an equivalent amount from the atmosphere. This usually occurs through, for example, planting trees, which sequester carbon in their wood.

The terms net zero and carbon neutral are often seen as interchangeable. But while net zero usually refers to all greenhouse gases, Chris Stark, chief executive of the UK government's advisory body the Committee on Climate Change (CCC), said his organisation mostly uses carbon neutral when referring to carbon dioxide emissions only.

Jim Watson, professor of energy policy at University College London (UCL), concurred with the CCC's definition but he added that it was "unfortunate" there was no universally agreed definition for the terms.

Small modular reactors (SMRs)

Mr Johnson wants new nuclear power for the UK but history has shown that the construction of large nuclear power plants often goes way over schedule and budget.

Several manufacturers are now trying to develop small modular plants as a “kit of parts“ that can be assembled on site. The idea is that factory-built modules will be constructed at scale to drive down costs but some experts are highly sceptical.

Supporters say that small nuclear reactors can be unobtrusive and safe

Hydrogen power

Hydrogen is the lightest element on Earth. When it’s used as a source of energy, it produces no direct carbon emissions.

It can be used either in fuel cells, or burned in internal combustion engines.

Several industries hope hydrogen will replace the natural gas they burn and some transport experts believe hydrogen fuel cells will increasingly be used to power vehicles.

A fuel cell is an ingenious piece of equipment that converts chemical energy into electrical energy. This can be used, say, to power a lorry. Many fuel cells combine hydrogen and oxygen to generate electricity - with water and heat as by-products.

A key question is whether the hydrogen used for energy is itself from fossil gas. A key process for producing hydrogen in this way, known as steam reforming, also emits troublesome carbon dioxide and is expensive.

Hydrogen can also be manufactured by “splitting“ water using wind energy, which is clean but even more costly.

Nuclear fusion

Conventional nuclear power stations rely on a process called fission, where a heavy chemical element is split to produce lighter ones.

But nuclear fusion works by combining two light elements to make a heavier one.

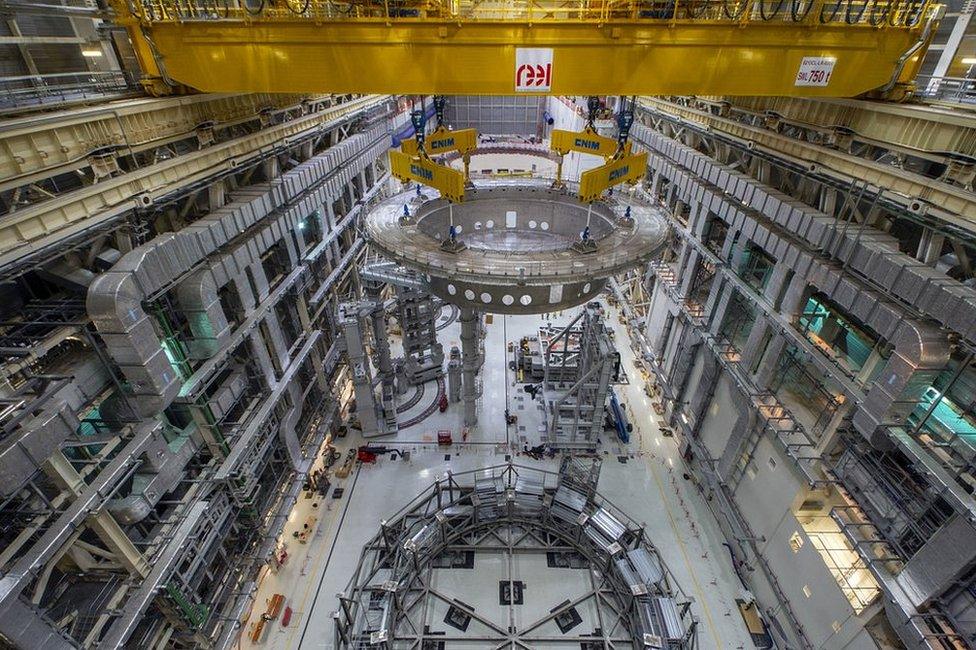

Iter: the world's biggest nuclear fusion project is under construction in France

It's an attempt to replicate the processes of the Sun here on Earth. Nuclear fusion has been a dream of scientists for decades, because, like the Sun, it could act as an almost limitless source of energy.

Further attractions include cheap fuel, relatively little radioactive waste and no emissions of greenhouse gases. But getting more energy out than you put in remains immensely challenging and, since the 1950s, it's been touted as being "30 years away".

COP meetings

This time next year – postponed from 2020 because of Covid-19 – the UK will host a crucial meeting of world leaders known as COP26. It’s where delegates from nations across the globe agree what they're going to do hold back climate change.

COP stands for Conference of the Parties. It will be attended by countries that signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) - back in 1992. This year's meeting will be the 26th, which is why it's called COP26.

NDCs

Next month, Prime Minister Boris Johnson will convene a virtual summit where leaders will be asked to offer their NDCs for tackling climate change. NDCs are Nationally Determined Contributions - in other words, voluntary offers by nations to cut their own emissions.

The timeframe in focus is up to 2030, and if the UK wants to encourage other countries to make cuts that are equal to the challenge, Mr Johnson must make an ambitious pledge with far-reaching effects across the economy.

Carbon budgets

This is a restriction that's placed on the total amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted over a set period of time. The UK uses carbon budgets to keep on track with its strategy of switching over to a low-carbon economy.

The next budget, to be set next month, will carry Britain through to 2037, by which time it should be on track for net zero in 2050.

Follow Roger on Twitter., external