Coronavirus variants and mutations: The science explained

- Published

The rapid spread of coronavirus variants has put the world on alert and triggered a new lockdown in the UK. What are these variants and why are they causing concern?

All viruses naturally mutate over time, and Sars-CoV-2 is no exception.

Since the virus was first identified a year ago, thousands of mutations have arisen.

The vast majority of mutations are "passengers" and will have little impact, says Dr Lucy van Dorp, an expert in the evolution of pathogens at University College London.

"They don't change the behaviour of the virus, they are just carried along."

But every once in a while, a virus strikes lucky by mutating in a way that helps it survive and reproduce.

"Viruses carrying these mutations can then increase in frequency due to natural selection, given the right epidemiological settings," Dr van Dorp says.

This is what seems to be happening with the variant that has spread across the UK, known as 202012/01, and a similar, but different variant, recently identified in South Africa (501.V2).

Hundreds of thousands of viral genomes have been analysed across the world

There is no evidence so far that either causes more severe disease, but the worry is that health systems will be overwhelmed by a rapid rise in cases.

In a rapid risk assessment of these "variants of concern",, external the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control said they place increased pressure on health systems.

"Although there is no information that infections with these strains are more severe, due to increased transmissibility, the impact of Covid-19 disease in terms of hospitalisations and deaths is assessed as high, particularly for those in older age groups or with co-morbidities," the EU agency said.

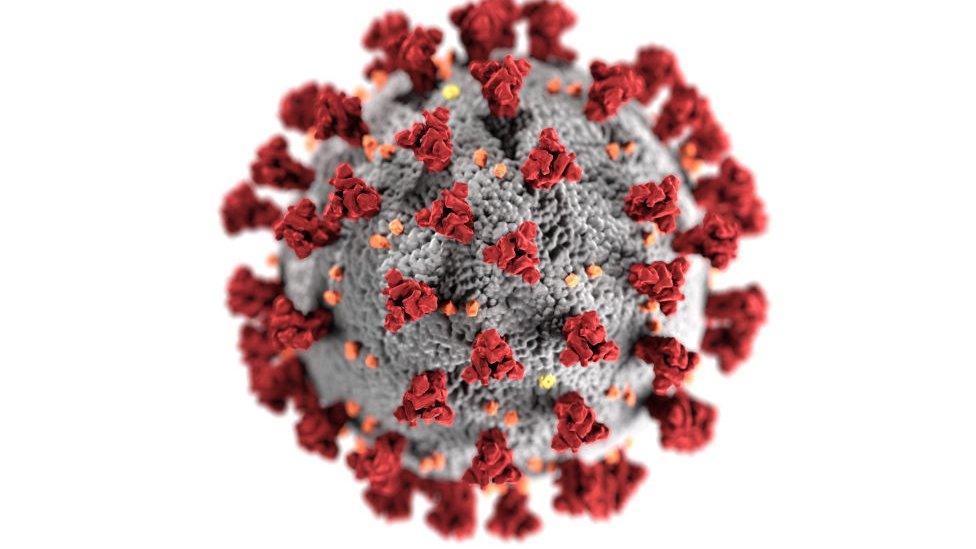

The variants have different origins but share a mutation in a gene that encodes the spike protein, which the virus uses to latch on to and enter human cells.

Scientists think this could be why they appear more infectious.

"The UK and South African virus variants have changes in the spike gene consistent with the possibility that they are more infectious," says Prof Lawrence Young at the University of Warwick.

But as Dr Jeff Barrett, director of the Covid-19 genomics initiative at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Hinxton, UK, points out, it's the combination of what the virus is doing and what we're doing that determines how fast it spreads.

"With the new variant, the situation changes more quickly as restrictions are relaxed and tightened, and there is less room for error in controlling the spread," he says.

"We don't have any evidence, however, that the new variant can fundamentally evade masks, social distancing, or the other interventions - we just need to apply them more strictly."

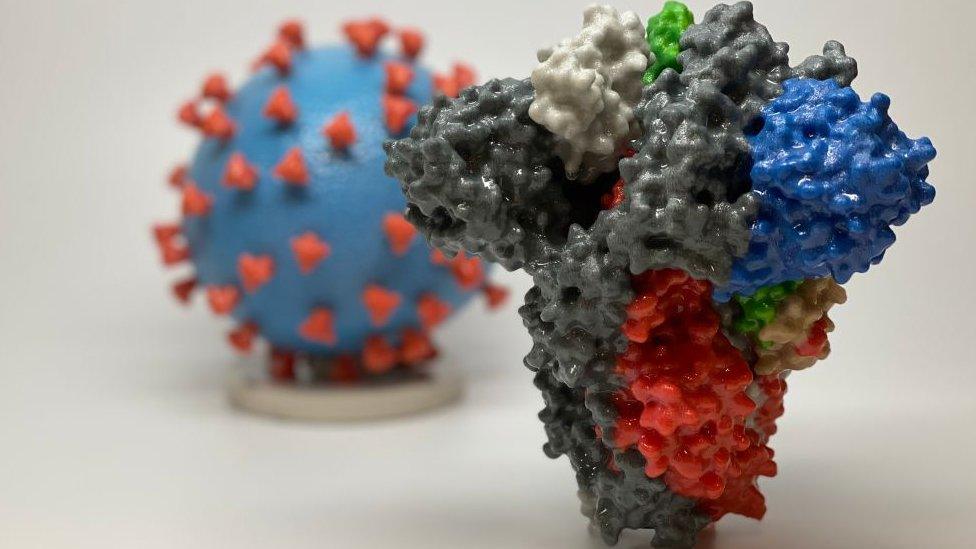

The spike protein (foreground) enables the virus to enter and infect human cells

With vaccine roll-out underway, scientists are racing to understand the repercussions for vaccines, which are based on the spike protein sequence.

There is particular concern about the South Africa variant, which has several changes in the spike (S) protein.

Most experts think vaccines will still be effective, at least in the short term.

Dr Julian W Tang, a virologist at the University of Leicester, says vaccines can be modified to be "more close-fitting and effective against this variant in a few months".

"Meanwhile, most of us believe that the existing vaccines are likely to work to some extent to reduce infection/ transmission rates and severe disease against both the UK and South African variants - as the various mutations have not altered the S protein shape that the current vaccine-induced antibodies will not bind at all."

Mink outbreaks are a "spillover" from the human pandemic

Scientists are carrying out laboratory studies to find out more about the variants. And they are tracking every move of the virus as it hopscotches around the world.

By taking a swab from an infected patient, the genetic code of the virus can be extracted and amplified before being "read" using a sequencer.

The string of letters, or nucleotides, allows genomes and mutations to be compared.

"It is thanks to these efforts, and UK testing laboratories, that the UK variant has been flagged so quickly as a potential cause of concern," Dr van Dorp says.

Prof Julian Hiscox, chair in infection and global health at the University of Liverpool, says that, through the efforts of scientists to sequence the virus, "we've got a really good handle on variants that emerge".

In the short-term, only the harshest of lockdowns will reduce case numbers, he says.

"What lockdown does is reduce the number of people with the virus and reduce the amount of virus out there and that's a good thing."

But in the long term, Prof Hiscox suspects, we may face a scenario like flu, where new vaccines are developed and administered every year.

"The problem is, the more variants we get, the greater the chance the virus will be able to escape part of the vaccine - and this may reduce [its] efficacy," he says.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.

Related topics

- Published20 December 2020