Climate change: Weakened 'ice arches' speed loss of Arctic floes

- Published

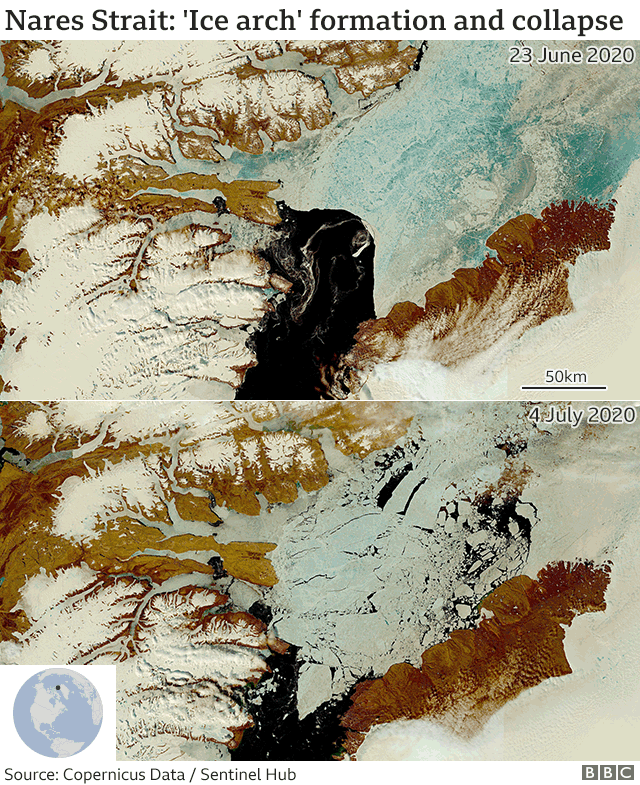

Look down on the Arctic from space and you can see some beautiful arch-like structures sculpted out of sea-ice.

They form in a narrow channel called Nares Strait, which divides the Canadian archipelago from Greenland.

As floes funnel southward down this restricted conduit, they ram up against the coastline to form a dam, and then everything comes to a standstill.

"They look just like the arches in a gothic cathedral," observes Kent Moore from the University of Toronto.

"And it's the same physics, even though it's ice. The stress is being distributed all along the arch and that's what makes it very stable," he told BBC News.

But the UoT Mississauga professor is concerned that these "incredible" ice forms are actually being weakened in the warming Arctic climate. They're thinning and losing their strength, and this bodes ill, he believes, for the long-term retention of all sea-ice in the region.

Directly to the north of Nares Strait is the Lincoln Sea. It's where you'll find some of the oldest, thickest floes in the Arctic Ocean.

It's this ice that will be the "last to go" when, as the computer models predict, the Arctic becomes ice-free during summer months sometime this century.

There are essentially two ways this old ice can be lost.

It can be melted in place in the rising temperatures or it can be exported. And it's this second mode that's in play in Nares Strait.

The 40km-wide channel's arches act as a kind of valve on the amount of sea-ice that can be pushed out of the Arctic by currents and winds.

When stuck solidly in place, typically from January onwards - the arches shut off all transport (sea-ice can still be exported from the Arctic via the Fram Strait, which is the passage between eastern Greenland and Svalbard).

But what Prof Moore's and colleagues' satellite research has shown is that these structures are becoming less reliable barriers.

They are forming for shorter periods of time, and the amount of frozen material allowed to pass through the strait is therefore increasing as a consequence.

"We have about 20 years of data, and over that time the duration of these arches is definitely getting shorter," Prof Moore explained.

"We show that the average duration of these arches is decreasing by about a week every year. They used to last for 250-200 days and now they last for 150-100 days. And then as far as the transport goes - in the late 1990s to early 2000s, we were losing about 42,000 sq km of ice every year through Nares Strait; and now it's doubled: we're losing 86,000 sq km."

Prof Moore says we need to hang on to the oldest ice in the Arctic for as long as possible.

If the world manages to implement the ambition of the Paris climate accord and global warming can be curtailed and reversed, then it's the thickest ice retained along the top of Canada and Greenland that will "seed" the rebound in the frozen floes.

The area of oldest, thickest ice, he adds, is also going to be an important refuge for those species that depend on the floating floes for their way of life - the polar bears, walruses and seals.

"My concern is that this last ice area may not last for as long as we think it will. This is ice that is five, six, even 10 years old; so if we lose it, it will take a long time to replenish even if we do eventually manage to cool the planet."

Prof Moore and colleagues have published their latest research in the journal Nature Communications, external.