SLS: Nasa finds cause of 'megarocket' test shutdown

- Published

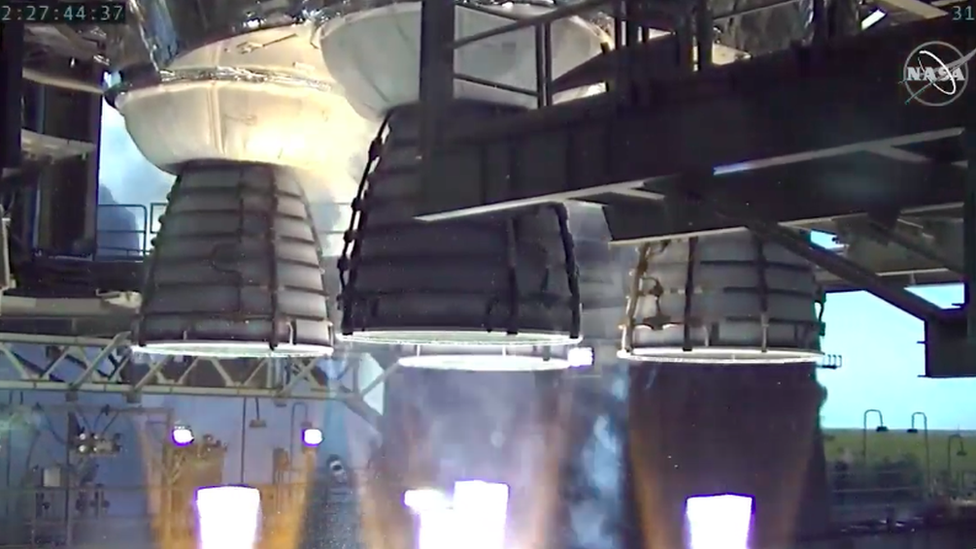

The four main engines were fired in unison for the first time, but had to be shut down early

An issue with hydraulic systems led to the premature shutdown of a key test for Nasa's new "megarocket".

Officials said the way components had been set up to respond in the test was "a little conservative" and that this led to the early stop.

Contrary to earlier concerns, there was no sign of damage to the huge core stage of the Space Launch System (SLS).

More powerful even than the Apollo-era Saturn V, the SLS will return astronauts to the Moon this decade.

Hydraulics are used to apply force using pressurised fluids.

The rocket consists of a core stage, with four RS-25 engines at its base, and two smaller solid rocket boosters (SRBs) attached to its sides.

Later this year, it had been due to launch Nasa's next-generation crew vehicle - Orion - on a loop around the Moon. No astronauts will be aboard for that mission, which is primarily intended to test the hardware.

Nasa is still undecided about whether it will try to re-run the test, or ship the 65m-long vehicle section to Florida's Kennedy Space Center (KSC), where it will be prepared for its maiden flight.

Despite speculation that the November 2021 launch date will slip, officials said the SLS could still make that date.

On Saturday, engineers from Nasa and Boeing - the rocket's prime contractor - conducted a "hotfire" test of the rocket's four powerful RS-25 engines at Stennis Space Center, near Bay St Louis in Mississippi.

All four of the core stage engines thunder to life during Saturday's test

The core stage was anchored to a massive steel structure called the B-2 test stand on the grounds of the Stennis facility.

After filling the rocket segment with more than 700,000 gallons of liquid hydrogen and oxygen propellant, they had hoped the RS-25 units would fire for eight minutes - roughly the amount of time it takes for the SLS to get to space.

However, teams would have obtained all the engineering data they needed to certify the rocket for flight after 250 seconds.

In the event, the engines thundered to life on Saturday evening (GMT), generating a massive plume of exhaust that dwarfed the trees surrounding the test site. However, they shut off after just over a minute of firing.

During a news conference, John Honeycutt, SLS programme manager at Nasa's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, said the core stage and the RS-25 engines had "performed perfectly".

He added: "We've learned from the data that the shutdown did occur as the result of a couple of test parameters we had set on the hydraulic system that's powered by the core stage auxiliary power units.

"What we've done for this test programme, in order to protect the flight hardware, is intentionally be a little conservative with our test parameters."

Nine lives

There are four of these auxiliary power units in the core stage. The hydraulic system that they power is responsible for "gimballing", or pivoting, the four engines so that the rocket can be steered during flight.

"On auxiliary power unit 2, we saw a low indication on the hydraulic reservoir level, and the hydraulic pressure. Those two 'low cuts' went through their checks over a series of milliseconds," said Honeycutt.

"And on the three checks that it took, it stayed low and it sent the command to the flight computer to advance the shutdown."

He said that this issue would not have caused any interruption on a real flight of the rocket.

Honeycutt also explained that teams were currently crunching data from Saturday's test, and that the results of this review would determine whether Nasa and Boeing set up another test at Stennis or sent the stage to Florida.

One consideration is that the core stage propellant tanks can only be filled with hydrogen and oxygen a total of nine times. Engineers have already filled them three times.

Saturday's test was the eighth and final test of the Green Run programme of evaluation for the core stage, designed to iron out any problems before it is used to launch Orion.

This mission is known as Artemis-1, and is the first launch in Nasa's planned programme of lunar exploration. By 2024, the agency wants to land humans on the Moon for the first time since 1972.

Discussing the potential knock-on effects of the test issue on the launch schedule for Artemis-1, Nasa administrator Jim Bridenstine said: "Is it within the realm of possibility to launch [Artemis-1] by 2021? Yes, it is still within the realm of possibility."

Artwork: Nasa wants to return to the Moon, but this time it wants to stay

He also said that Nasa was hitting the milestones needed to meet the 2024 date for astronauts returning to the Moon.

The Artemis plan also aims to establish a long-term human presence on the Moon as part of what Nasa calls a "sustainable" programme of exploration.

Mr Bridenstine, a Trump appointee who is stepping down following the 2020 presidential election, expressed his hope that the priorities of human exploration could remain above party politics, something that he said had not always been the case in the past.

The Democratic party platform for the election was broadly supportive of the Moon plan. But there is little detail on President-elect Joe Biden's attitude to the space programme.

"It must be said, and this is so important, that we have strong, bipartisan, apolitical support for the Artemis programme," Mr Bridenstine explained, adding that he believed Nasa could come up with a range of options for human exploration that the incoming administration could buy into.

"These are not programmes for one term, these are programmes that need to withstand multiple administrations."

Follow Paul on Twitter., external