US rejoins Paris accord: Biden's first act sets tone for ambitious approach

- Published

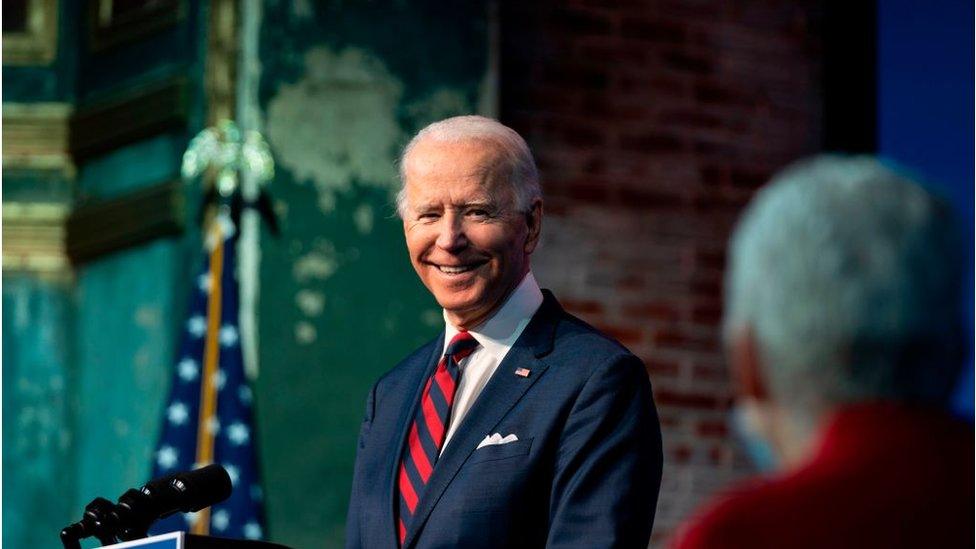

President Biden introducing members of his climate and energy team

Make no mistake, returning to the Paris climate agreement is not mere symbolism - it is an act cloaked in powerful, political significance.

While re-joining the pact was actually quite simple - the signing of a letter on Biden's first day in office and then a 30-day wait which ends on Friday - there could be no more profound signal of intention from this incoming administration.

Coming back to Paris means the US will once again have to follow the rules.

Those rules mean that sometime this year the US will need to improve on their previous commitment, made in the French capital in 2015, to cut carbon emissions.

This new target, possibly for 2030, and President Biden's commitment to reaching net zero emissions by 2050, will be the guide rails for the US economy and society for decades to come.

Coming back to Paris really means it is no longer "America First".

It signals that the spirit of that awkward word, "multilateralism", is alive and well and living once again in the White House.

But the US also needs to tread carefully and remember that the world's perspective on climate change has moved on since the Obama days.

"I think the United States needs to recognise that the world is very different than it was four years ago and enter in, in partnership and humility, not coming back in telling everybody what they should be doing, because the world's gone on," said Jennifer Morgan, executive director of Greenpeace International.

Wildfires in California have been associated with climate change

"I think the expectation's there, if you look at global climate politics, that climate will now play a role in security policy.

"Fossil fuels are like weapons of mass destruction - they need to be kept in the ground."

That sentiment found an echo in President Biden's other executive action on his first day.

His cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline permit is a carefully calculated message to the oil industry.

"This new executive order on the Keystone pipeline is a very tangible, visible decision," said Rémy Rioux, the head of the French development agency and a negotiator for the French government during the Paris climate talks.

"The US is saying 'we're back' - and 'not only are we back on track, but we're back with a fuller commitment and momentum'."

Rolling back the rollbacks

During his time in office, President Trump did his utmost to remove what he perceived as unnecessary barriers and red tape to the freedoms of industry and commerce.

President Trump announcing a review of the National Environmental Policy Act: Experts believe President Biden will rescind the rollback

This drive seemed especially powerful when it came to anything related to climate change.

At the Columbia University Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, external in New York, researchers have tracked around 175 rollback actions taken by the Trump administration to eliminate federal climate mitigation and adaptation measures.

With President Biden vowing to overturn the rollbacks, Prof Michael Gerrard, who runs the Sabin Center, explained what his top three targets should be and why.

Motor vehicle emissions: "These are the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the US. President Obama greatly strengthened the emissions and fuel economy standards, reducing air pollution and saving consumers a great deal of money at the gas pump. Donald Trump weakened these standards, benefiting no-one but the oil companies. I expect President Biden will restore the standards and make them even stronger going forward."

Methane: "This is a powerful greenhouse gas and it's the chief component of natural gas. A great deal escapes during the production, transport and processing (of natural gas). President Trump revoked the Obama rules controlling this leakage. It's likely that President Biden will put them back and make them apply more broadly."

Coal-fired power plants: "These are the second largest source of greenhouse gases. Obama created the Clean Power Plan to reduce these emissions. Trump revoked that plan and replaced it with the toothless Affordable Clean Energy Rule. The US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia has thrown out the Trump rule, clearing the path for Biden to craft a new rule on coal plants."

The new president has highlighted the existential threat posed by climate change. It is, along with the pandemic, the economy and racial justice, one of the four cornerstone crises facing the new administration.

But climate change is also threaded through each of the others, and tackling the root causes of rising temperatures can benefit these other pressing problems as well.

There's a slightly more elegant word for it derived from the natural world - symbiosis.

In the way that bees spread the pollen of flowers while gathering nectar for themselves, it refers to the interaction between different organisms to the advantage of both.

"People in the US are seeing the hurricane, they're seeing the fires, they're seeing the droughts, and they know that something needs to be done," said David Waskow from the World Resources Institute.

US protestors demonstrate against a new oil pipeline: Some hope that such infrastructure projects will be cancelled by the incoming administration

"The good news is that so many of the climate solutions can boost the economy, can generate jobs.

"It's not a trade-off between tackling the economic situation and tackling the climate crisis; in fact, they have to go hand in hand."

In the days ahead, we'll get a clearer view of how the new president will aim to tackle these challenges.

While campaigning, external, he highlighted electric vehicles and charging infrastructure, building high-speed railways, and improving energy efficiency in homes and offices.

Tackling the energy sector remains key though, with President Biden committed to 100% clean electricity by 2035.

To get there, the Biden team may push Congress to pass a clean electricity standard that would set a target for green energy but leave it up to utilities to find the best way to meet the goal.

There may also be a significant effort to rollback what environmentalists would see as the Trump administration's watering down of the National Environmental Policy Act, known as Nepa, external.

This 50-year-old law allowed federal agencies to examine big infrastructure projects, such as pipelines and power plants, for their environmental impacts. Crucially, it could evaluate the cumulative climate change impact of these ventures.

Former Secretary of State John Kerry will be President Biden's special envoy on climate change

This element was removed by the Trump administration.

"I think it will be a really important rollback if the US wants to reach net zero by 2050," said Prof Pam McElwee from Rutgers University in New Jersey.

"Nepa would be able to help with that long-term strategy, to help the US move away from building fossil fuel infrastructure. It could be a pretty strong tool in that arsenal."

While political opposition in Congress may see some compromises in the spirit of unity that President Biden underlined in his inaugural address, some experts don't see that as the biggest obstacle in Biden's path.

"I would say if anything that the biggest barrier is the physics of climate change," said Prof McElwee.

"The fact that we have to catch up makes things really, really challenging. And the scale of the challenge is really pretty overwhelming."

Follow Matt on Twitter., external

This article was first published on 20 January when Biden signed the act announcing the US would rejoin the Paris accord