Nasa's Perseverance rover is bearing down on Mars

- Published

Allen Chen: "When I look at Jezero Crater, I see danger"

The US space agency's Perseverance rover is now just three weeks from arriving at Mars.

The robot and the Red Planet are still separated by some 4.5 million km, external (3 million miles), but this gap is closing at a rapid rate.

The biggest, most sophisticated vehicle ever sent to land on another planet, the Nasa robot is being targeted at a near-equatorial crater called Jezero.

Touchdown is expected shortly before 2100 GMT on Thursday 18 February.

To get down, the Nasa rover, external will have to survive what engineers call the "seven minutes of terror" - the time it takes to get from the top of the atmosphere to the surface.

The "terror" is a reference to the daunting challenge that is inherent in trying to reduce an entry speed of 20,000km/h to something like walking pace at the moment of "wheels down".

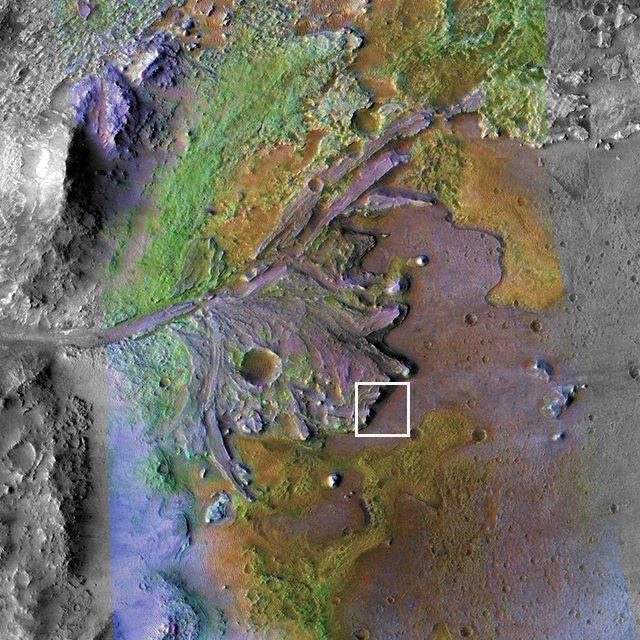

"When the scientists look at our landing site, Jezero Crater, they see the scientific promise of everything: the remains of an ancient river flowing in and flowing out of this crater and think that's the place to go to look for signs of past life. But when I look at Jezero, I see danger," says Allen Chen, the engineer who leads the Entry, Descent and Landing (EDL) effort for Perseverance.

"There's danger everywhere. There's this 60-80m-tall cliff that cuts right through the middle of our landing site. If you look to the west, there are craters that the rover can't get out of even if we were to land successfully in one of them. And if you look to the east, there are large rocks that our rover would be very unhappy about if we put down on them," he told BBC News.

"Dare mighty things": Watch how Perseverance's landing should proceed

Fortunately, Perseverance has some tried and tested technologies that should ensure it reaches a safe point on the surface. Among them is the famous "Skycrane" jet pack that successfully landed Nasa's previous rover, Curiosity, eight years ago.

There are even some additions designed to improve reliability. The parachute system that slows the atmospheric descent from super- to sub-sonic speeds now has something called "range trigger". This more precisely times the opening of the parachute to bring the rover closer to its notional bulls-eye.

Unlike Curiosity which just opened the chute when it reached a pre-determined velocity, Perseverance will check its surroundings first before issuing the command.

Allied to this is Terrain Relative Navigation. Perseverance will be examining the ground below and checking it against satellite imagery of the crater to better gauge its position.

It's like you or I looking out the window of our car and then looking back at a map to see where we are, says Chen.

"That's what we're asking Perseverance to do on her own, to figure out where she is, and then fly to known safe spots that are nearby."

Ken Farley: "How ubiquitous might life be beyond Earth?"

Curiosity managed to touch down about a mile from the notional bulls-eye. It overshot slightly. Perseverance, with its enhanced landing technologies, should do much better.

Scientists have already named the area that includes the bulls-eye. It's called Timanfaya, named after the Spanish national park in Lanzarote, one of the Canary Islands.

The Lanzarote Timanfaya is a volcanic terrain; the Martian version, which encompasses a 1.2km by 1.2km square likely also includes some volcanic rock. It's the floor of Jezero Crater.

Although this is the landing spot, it's not the major interest for the mission. That's the remnant delta just to the north, along with some more distant carbonate rocks which the researchers think may trace the edge of a once huge lake in Jezero.

"Carbonate rock is extremely abundant on Earth, but is quite rare on Mars and we're not really sure why that is," says Ken Farley, the Nasa project scientist on Perseverance.

"There's a region on the edge of the crater that would have been the shore with a high concentration of carbonate. This is very attractive to us, because on Earth carbonate often is precipitated [by living organisms]: people will be familiar with things like coral reefs. And it is a good way to record bio-signatures," he told BBC News.

Under the right conditions, stromatolites will form in shallow waters

The dream is Perseverance will stumble across fossil evidence of stromatolites. These are sedimentary deposits that have been built by layers, or mats, of micro-organisms.

The structures, and the chemistry within them, is recognisable to geologists. That said, we are talking about rocks in Jezero that are almost four billion years old.

Discoveries are unlikely to be of the slam-dunk variety, which is why Perseverance will package up its most interesting finds for later missions to retrieve and bring back to Earth for more detailed study.

Farley says Perseverance will be asking the most fundamental of questions and whatever answers its produces will be instructive.

"Is it a case of if you build a habitable environment then life will come? Or is it like a magic spark that also has to happen? And the answer to that question is really important, because we now know that there are billions, literally billions, of planets out there beyond Earth.

"What is the likelihood that life doesn't exist out there? It seems small to me, but it all hinges on how ubiquitous that spark is that gets life going," he explained.

The bulls-eye is in a square called Timanfaya. Carbonate rocks are coloured green