Square Kilometre Array: 'Lift-off' for world's biggest telescope

- Published

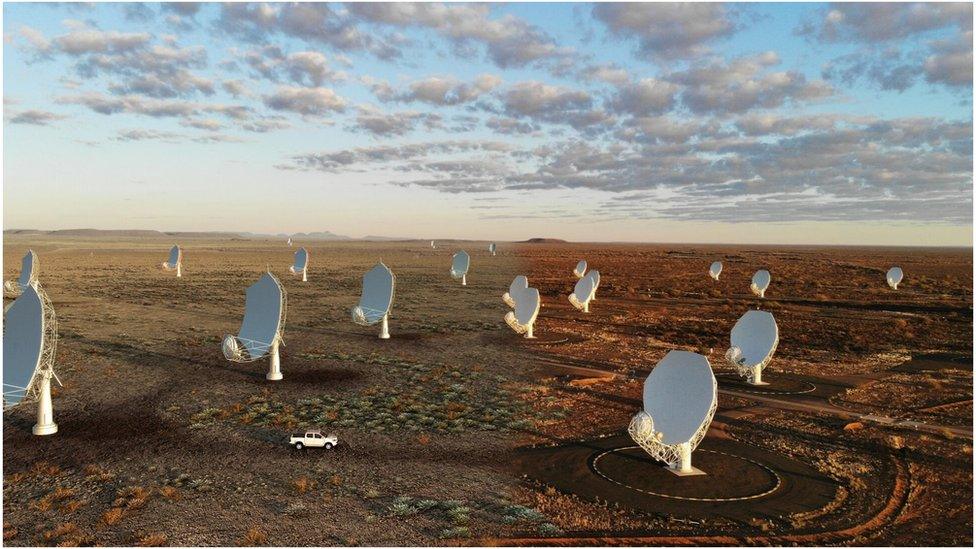

Artwork: The parabolic antennas will be sited in South Africa

One of the grand scientific projects of the 21st Century is 'Go!'.

The first council meeting of the Square Kilometre Array Observatory has actioned plans that will lead to the biggest telescope on Earth being assembled over the coming decade.

Member states approved a thousand pages of documents covering everything from the power to open a bank account to engaging with industrial contractors.

The SKA telescope will comprise a vast formation of radio receivers.

These will be positioned across South Africa and Australia.

The array's resolution and sensitivity, allied to prodigious computing support, will enable astronomers to address some of the most fundamental questions in astrophysics today.

How did the first stars come to shine in the Universe? What exactly is "dark energy" - the mysterious form of energy that appears to be driving the cosmos apart at an accelerating rate? And even the most basic question of all - are we alone? The SKA's unprecedented sensitivity would pick up any extra-terrestrial transmissions.

It has taken more than 30 years of planning to reach this point

The international treaty that underpins the new observatory came into force just last month, which enabled this first council meeting - conducted online because of Covid - to finally move forward on a project that has been more than 30 years in the formulation.

"I think of this council meeting really as marking the birth of the observatory," said Prof Phil Diamond, the SKAO's inaugural director general.

"We became a legal entity on the 15th of January following the UK's ratification of our convention. But at that stage, we were an empty vessel. And it's this first council meeting that is triggering everything that enables us to start filling that empty vessel," he told BBC News.

The council has approved a whole series of policies, regulations and procedures that will make the observatory real.

A key next step, of course, is to build the telescope. The expectation is that invitations to tender will go out to industry from July, with ground-breaking ceremonies anticipated towards the end of the year.

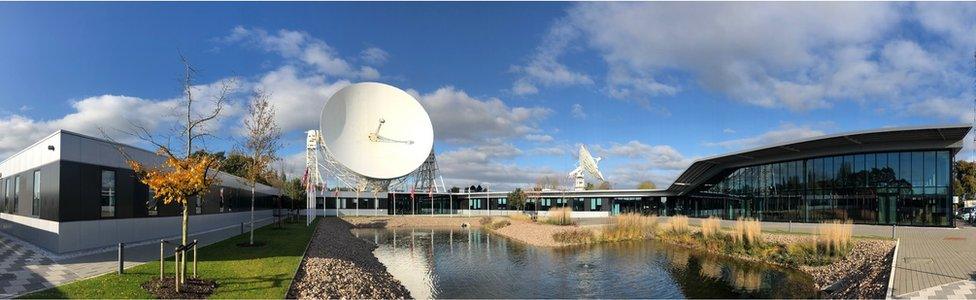

Jodrell Bank in the UK is the HQ, but Covid meant the council meeting was held online

The observatory is centred on remote, uninhabited locations in the Karoo in South Africa's Northern Cape, and in the Murchison in Western Australia.

The telescope will incorporate a mix of parabolic antennas, or “dishes”, as well as dipole antennas, which look a little like traditional TV aerials.

The aim is to construct an effective collecting area measuring hundreds of thousands of square metres.

The system will operate across a frequency range from roughly 50 megahertz to, ultimately, 25 gigahertz. In wavelength terms, this is in the centimetres to metres range.

With the engineered sensitivity, this should enable the telescope to detect very faint radio signals coming from cosmic sources billions of light-years from Earth, including those signals emitted in the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang when the first galaxies and stars started forming.

"We're entering an era when giant telescope will work together in the coming decades to try to understand the mysteries of the Universe," said SKAO council chair, Dr Catherine Cesarsky.

"Behind it all are many years of work by many people all over the world."

And Dr Leah Morabito, member of the UK SKA science committee, from Durham University, commented: "This is an historic step in the process of getting the SKA up and running, and especially after such a year of global uncertainty it is inspiring to shift our attention to the exciting future of the SKA."

The council meeting, held over Wednesday and Thursday, was led by the those countries that have ratified the SKA treaty: Australia and South Africa, as the telescope's host nations; Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal; and the United Kingdom, which functions as the organisation's HQ with offices at the famous Jodrell Bank radio observatory.

In attendance also were representatives from Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. They sat as observers at this stage because they haven't quite completed their parliamentary approvals that would enable them to ratify. All are expected to do so in due course.

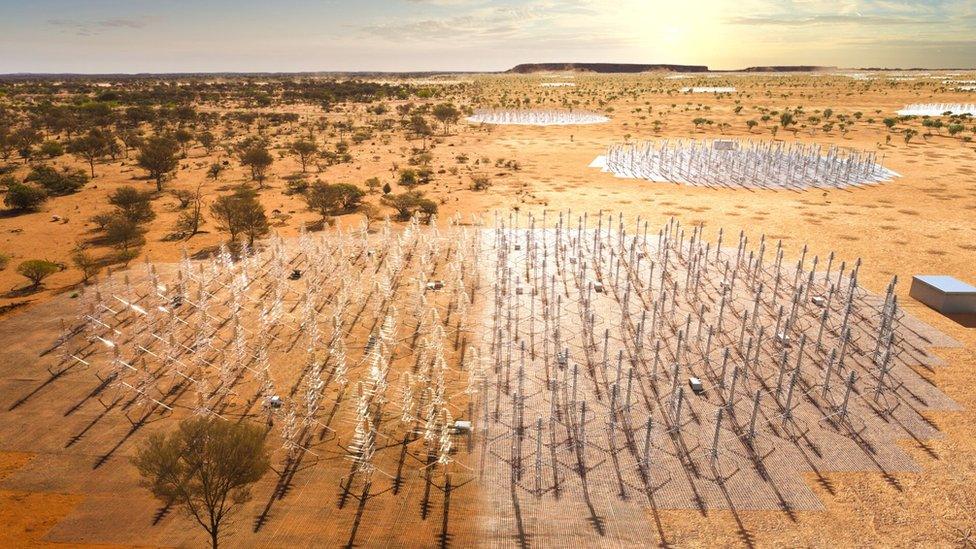

Artwork of Western Australia: It will take seven or eight years to fully build the SKA

Construction and operation of the SKA over this decade is likely to consume about €2bn (£1.8bn; $2.4bn).

"We reckon construction will take seven to eight years; we've put about 18 months of schedule contingency in there. That's until the full thing is built," explained Prof Diamond.

"But, as you know, because this is interferometer - an array of dishes - once we've got a significant fraction of them out there, we hope to be able to begin some early science because the science community is chomping at the bit to use this facility.

"Realistically, I'd say it'll be four or five years before we can start to let them play with the antennas."

Like many large astronomy facilities, the SKA has recently voiced its concern about the huge deployment of communications satellites currently under way.

For optical telescopes, spacecraft moving across the field of view can leave streaks in their imagery. For radio telescopes like the SKA, it is the downlink transmissions from the satellites that has the potential to create interference.

Prof Diamond said he was pleased to see the satellite companies engage in a constructive way with astronomers' concerns.

Among these companies are SpaceX, which now has well over a thousand spacecraft in orbit, and OneWeb, which hopes to have about half that number up there within a year and a half.

"It was a bit difficult to find anyone to talk to at OneWeb when they were in administration but since they've emerged from bankruptcy we've been able to re-engage with them. We've been working closely with industry under non-disclosure agreements that allow us to see their technical plans and specifications, and we're coming up with ideas about how to minimise the impacts," Prof Diamond said.