Ancient hunter-gatherer seashell resonates after 17,000 years

- Published

Listen to the sound of the conch shell horn

Archaeologists have managed to get near-perfect notes out of a musical instrument that's more than 17,000 years old.

It's a conch shell that was found in a hunter-gatherer cave in southern France.

The artefact is the oldest known wind instrument of its type. To date, only bone flutes can claim a deeper heritage.

The discovery is reported in the journal Science Advances, external.

Its significance lies in the dot-like markings inside the shell.

These match the artwork on the walls of the Marsoulas cave in the Pyrenees where the artefact was unearthed in 1931.

"This establishes a strong link between the music played with the conch and the images, the representations, on the walls," explained Gilles Tosello from the University of Toulouse. "To our knowledge this is the first time we can put in evidence a relationship between music and cave art in European pre-history."

The shell once belonged to a large sea snail of the species Charonia lampas

The shell measures 31cm in its longest dimension, and 18cm at its widest.

It was once home to a living organism, of course; most likely a species of cold-water Atlantic sea snail called Charonia lampas.

The shell must have been a prized object because the coastline where it was presumably picked up or traded is more than 200km away.

When the 1930s excavators at Marsoulas first looked at the shell, they thought it nothing more than a ceremonial drinking cup.

But the analysis by a team led from the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) has turned that interpretation on its head.

The scientists have identified the deliberate modifications that would have enhanced the shell's ability to make sound.

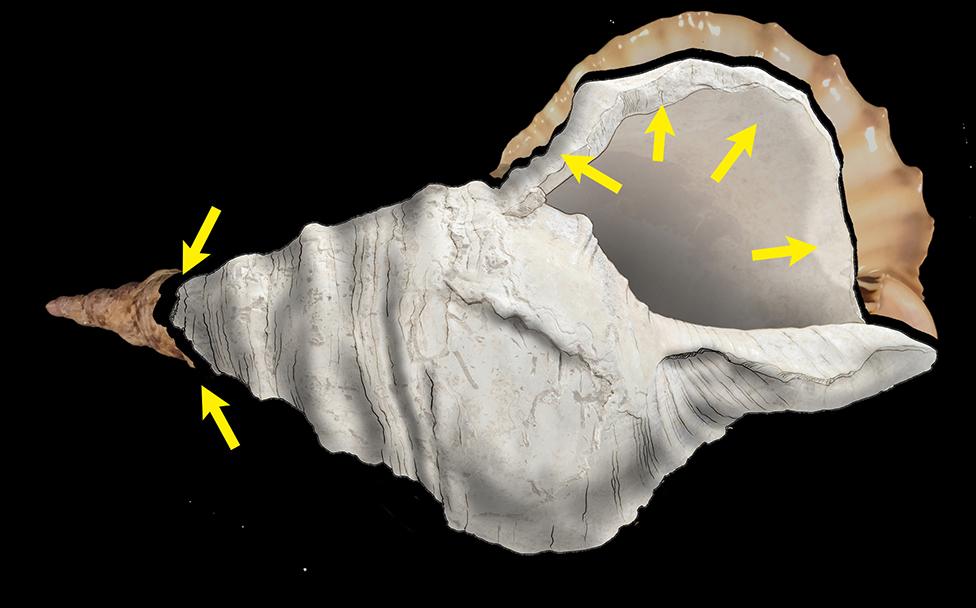

These include the hole excised at one end that would have permitted the insertion of some kind of mouthpiece, and cuts at the other end that would have made it easier to insert a hand to modulate the sound - in the same way a French horn player might insert their hand into the bell of the instrument to alter the pitch.

The team asked a professional musician to blow into the conch, and to their delight he was able to generate notes close to C, C-sharp and D.

"The intensity produced is amazing, approximately 100 decibels at one metre. And the sound is very directed in the axis of the aperture of the shell," said Philippe Walter from Sorbonne University.

Both ends of the conch were modified

Image processing enhancements were used to study the patterns painted on the inner-surface of the shell's opening.

These patterns, made with an iron oxide pigment (red ochre), take the form of fingerprints. The walls of Marsoulas cave share this style. There is a bison picture, for example, traced out by 300 finger dots.

The researchers have produced a 3D printed replica of the shell so they can further explore the musical possibilities of the conch without the risk of damaging the original artefact.

The Upper Palaeolithic people who owned the shell were part of what archaeologists call the Magdalenian tradition, which was notable for its particular approach to tool-making and use of bone, antler and ivory.

It's also known that the communities of the Pyrenees would interact with similar communities in the Cantabria region of coastal northern Spain. The conch therefore reinforces this relationship.

"The sound of this conch is a direct link with Magdalenian people," said Carole Fritz, the lead CNRS scientist on the project team.

An example of a New Zealand conch with its mouthpiece made of a decorated bone tube