Robots deployed at A68A mega-iceberg remnants

- Published

A robotic glider goes over the side of the James Cook

UK scientists have arrived at the remains of what was once the biggest iceberg in the world to investigate their impacts on the environment.

A68A, which for a long time had an area equal to a small country, gradually fragmented after drifting away from Antarctica into the South Atlantic.

The RRS James Cook approached the biggest remaining segment on Sunday.

It deployed a robotic glider that will measure seawater salinity, temperature and chlorophyll close to the ice.

This is information that will tell the scientists how the still significant blocks could be affecting local marine life.

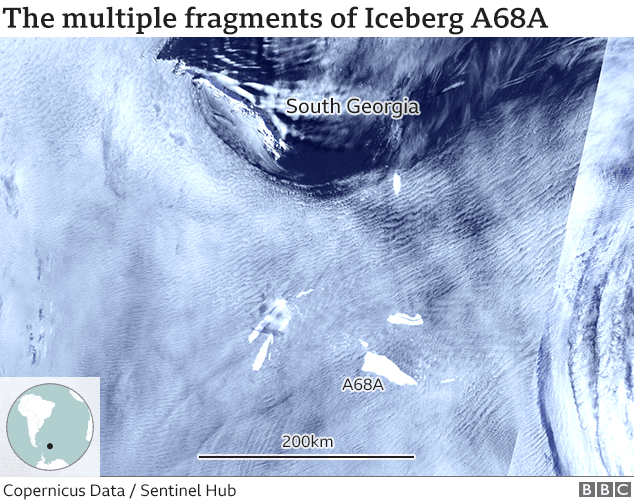

Originally some 5,800 sq km in size, A68a has now broken into many smaller pieces

The research ship doesn't need to stay in the vicinity because the technology built into the underwater robots means they can be piloted remotely back in the UK.

"We have developed a world leading web application to pilot and manage the data from long-range ocean robots," said Maaten Furlong, from the National Oceanography Centre (NOC).

"It uses satellite data to assist in piloting the gliders which can be deployed from anywhere in the world. We use a variety of different glider types that can be fitted with a bespoke combination of sensors as required by different science campaigns."

NOC is working with the British Antarctic Survey on the glider investigation.

The joint team aimed to put a second glider in the water on Monday. The James Cook has to be cautious, however. It is not an ice-breaker and the waters around the berg remnants are infested with smaller ice chunks that could do damage to its hull.

The gliders will gather measurements under and around the iceberg fragments

A68A has spent several months now drifting around the South Atlantic island of South Georgia, a haven to countless penguins, seals and an increasing number of great whales.

Researchers want to understand how large ice masses could affect the productivity of the waters off the British Overseas Territory.

One the one hand, icebergs can be a positive because they disperse rocky debris picked up in the Antarctic which then fertilises the ocean.

On the other hand, their great bulk can also be a negative by blocking predators' access to prey, or by dumping so much fresh meltwater they disrupt some of the normal processes in the marine food web.

A view from the bridge: The largest remnant is visible in the distance

A68A is now a shadow of its former self.

When it first calved from an Antarctic ice shelf in mid-2017, it covered an area of about 5,800 sq km - roughly a quarter of the size of Wales.

Even by the time it arrived in the warmer climes of South Georgia in early December, it had managed to hold on to a substantial portion of this original mass. Something in the region of 4,000 sq km.

But recent weeks have witnessed a rapid disintegration.

Iceberg fragments are named in a sequence. The original block carries the "A" suffix, with each subsequent segment given a letter further up the alphabet. As of Monday, the US National Ice Center, which curates this nomenclature, had recognised "daughter" bergs up to A68P.

A68A is still the single largest segment, but now measures less than 800 sq km.

The gliders can be piloted from a distance - from the UK, even