Oceans' extreme depths measured in precise detail

- Published

There is a surprising amount of life in the darkness of the Mariana Trench

Scientists say we now have the most precise information yet on the deepest points in each of Earth's five oceans.

The key locations where the seafloor bottoms out in the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic and Southern oceans were mapped by the Five Deeps Expedition, external.

Some of these places, such as the 10,924m-deep (6.8 miles) Mariana Trench in the western Pacific, had already been surveyed several times.

But the Five Deeps project removed a number of remaining uncertainties.

For example, in the Indian Ocean, there were two competing claims for the deepest point - a section of the Java Trench just off the coast of Indonesia; and a fracture zone to the southwest of Australia.

The rigorous measurement techniques employed by the Five Deeps team confirmed Java to be the winner, but this lowest section in the trench - at a depth of 7,187m - is actually 387km from where previous data had suggested the deepest point might be.

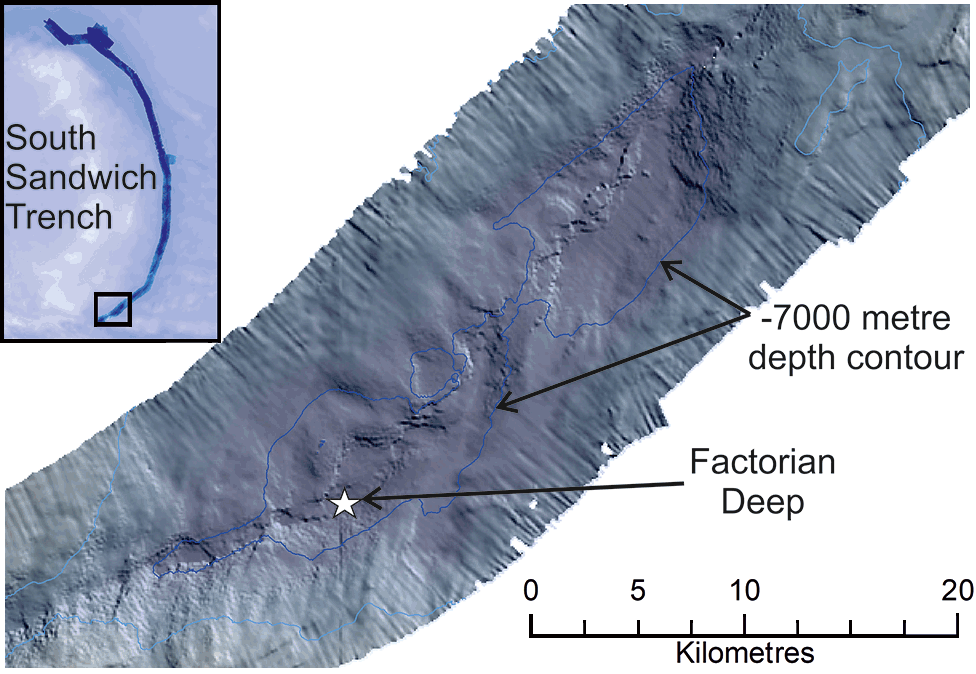

Likewise, in the Southern Ocean, there is now a new place we must consider that region's deepest point. It's a depression called Factorian Deep at the far southern end of the South Sandwich Trench. It lies 7,432m down.

There is a location in the same trench, just to the north, that's deeper still (Meteor Deep at 8,265m) but it's technically in the Atlantic Ocean. The dividing line with the Southern Ocean starts at 60 degrees South latitude.

Mariana Trench: Deep ocean trenches occur where Earth's tectonic plates meet

All of the new bathymetry (depth data) is contained in a paper published in the Geoscience Data Journal, external.

Its lead author is Cassie Bongiovanni from Caladan Oceanic LLC, external, the company that helped organise the Five Deeps Expedition, which had as its figurehead the Texan financier and adventurer Victor Vescovo.

Dr Heather Stewart: "We found over 100 new seamounts in the South Sandwich Trench"

The former US Navy reservist wanted to become the first person in history to dive to the lowest points in all five oceans and achieved this goal when he reached a spot known as the Molloy Hole (5,551m) in the Arctic on 24 August, 2019.

But in parallel to Mr Vescovo setting dive records in his submarine, the Limiting Factor, his science team were taking an unprecedented number of measurements of the temperature and salinity (saltiness) of the seawater at all levels down to the ocean floor.

This information was crucial in correcting the echo-sounder depth readings made from the hull of the sub's support ship, the Pressure Drop. The reported depths therefore have high confidence, even if they come with uncertainties of plus or minus 15m.

In this context, refining the observations any further will be extremely hard.

The wider context here is the quest to get better mapping data of the seabed in general. Current knowledge is woeful. Roughly 80% of the global ocean floor remains to be surveyed to the modern standard delivered by the likes of the Five Deeps Expedition.

"Over the course of 10 months, as we visited these five locations, we mapped an area the size of continental France. But within that was an area the size of Finland that was totally new, where the seafloor had never been seen before," explained team-member Dr Heather Stewart from the British Geological Survey.

"It just shows what can be done, what still needs to be done. And the Pressure Drop continues to work, so we are gathering more and more data," she told BBC News.

Factorian Deep is at 60.4 degrees South, and therefore just in the Southern Ocean

All of this information is being handed over to the Nippon Foundation-GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project, external, which aims to compile, from various data sources, a full-ocean depth map by the end of the decade.

It would be a critical resource. Better seafloor maps are needed for a host of reasons.

They are essential for navigation, of course, and for laying underwater cables and pipelines.

They are also important for fisheries management and conservation, because it is around the underwater mountains that wildlife tends to congregate. Each seamount is a biodiversity hotspot.

In addition, the rugged seafloor influences the behaviour of ocean currents and the vertical mixing of water. This is information required to improve the models that forecast future climate change - because it is the oceans that play a pivotal role in moving heat around the planet.

Victor Vescovo spoke to the BBC on completion of his historic five dives

And if you want to understand precisely how sea-levels will rise in different parts of the world, good ocean-floor maps are a must.

The BBC made contact at the weekend with the Pressure Drop, which is currently sailing west of Australia in the Indian Ocean.

Team-member and co-author on the new paper, Prof Alan Jamieson, is still aboard. He said the research ship was making discoveries every time it sent instrumentation into the deep.

"For example, there are some major animal groups in the world for which we just don't know how deep they go. Just last month, we recorded a jellyfish 1,000m deeper than 9,000m, which was the previous record by us. So we've now got jellyfish down to 10,000m.

"Three weeks ago, we saw a squid at 6,500m. A squid at that depth! How did we not know this? And during the Five Deeps Expedition, we added 2,000m on the depth range for an octopus.

"These are not obscure animals; it's not like they're some sort of rare species. These are big animal groups that are clearly occupying much larger parts of the world than we thought," Prof Jamieson said.

Prof Jamieson's team profiled water temperature and salinity at all depths

The deepest place in the Atlantic is in the Puerto Rico Trench, a place called Brownson Deep at 8,378m. The expedition also confirmed the second deepest location in the Pacific, behind the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. This runner-up is the Horizon Deep in the Tonga Trench with a depth of 10,816m.