Wastewater is 'polluting rivers with microplastic'

- Published

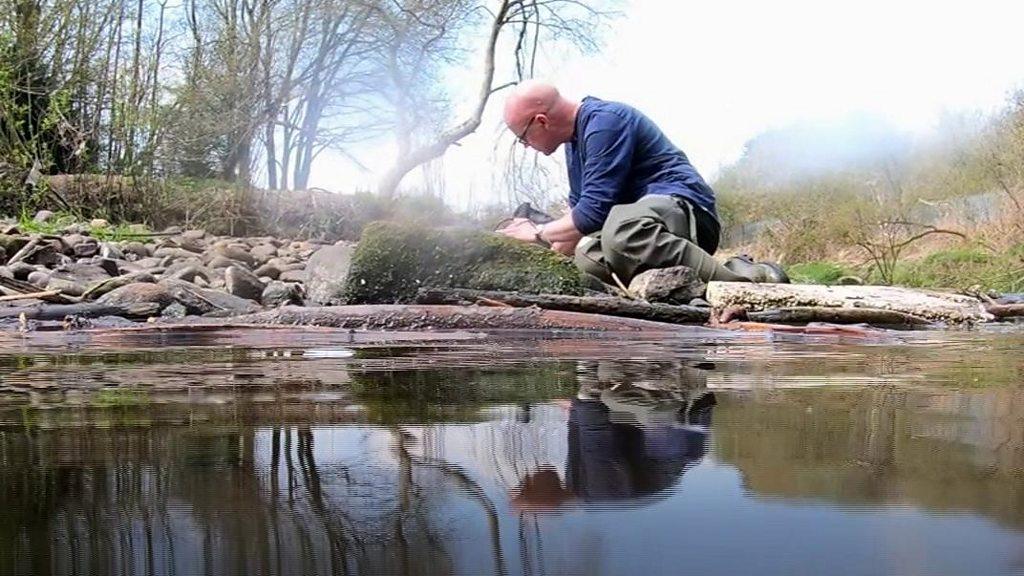

Lead researcher Professor Woodward examines the most contaminated site in the River Tame

Untreated wastewater "routinely released into UK rivers" is creating microplastic hotspots on riverbeds.

That is the conclusion of a study in Greater Manchester, which revealed high concentrations of plastic immediately downstream of treatment works.

The team behind the research concluded: untreated wastewater was the "key source" of plastic pollution.

The water company that operates along the river the scientists studied said it didn't "fully accept" the findings.

But the scientists, who published their research in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Sustainability, external, say sewer overflow pipes and outflows from treatment plants can release millions of plastic particles in a day.

Microplastic fibres, fragments and beads build up in the riverbed until a flood flushes them downstream

Lead researcher Prof Jamie Woodward from the University of Manchester told BBC News that, at the most contaminated site in the River Tame, where the team carried out their study, there were "concentrations over 130,000 microplastic particles per kilogram of sediment on the riverbed".

"So for every single gram of sediment, there were 130 particles - extraordinarily high levels of contamination.

"It's clear that wastewater is the key source of microplastics in our rivers."

Researchers compared their sediment samples to water they collected from sewer overflows

While the water company, United Utilities, declined to be interviewed, Jo Harrison, the company's director of environment said in a statement: "We understand that wastewater will be a contributing factor to microplastics pollution. We are involved in a wider two-year study, beginning this summer... to understand the sources and consequences of microplastics in the environment."

A spokesperson for the Environment Agency, which regulates the activities of the water industry added that the agency was "aiding water industry research in this area".

Water companies are permitted to release untreated wastewater when the pipes in their plants are overwhelmed by excess rainwater. But the researchers say that they measured build-ups of plastic during a dry summer period.

"To produce such high levels of contamination, [they] must be releasing wastewater into low flows - so when there isn't heavy rain," said Prof Woodward.

"It's almost become routine for many water companies to do this."

An Environment Agency report published earlier this year seemed to confirm that conclusion, revealing that water companies discharged raw sewage into UK rivers 400,000 times in 2020. And a recent study using artificial intelligence to detect sewage spills showed that hundreds more releases were simply going unrecorded and unreported.

Prof Jamie Woodward at work on the banks of the River Tame

Commenting on the recent study, Prof Andrew Johnson, from the UK's Centre for Ecology and Hydrology (CEH) in Wallingford, said that wastewater from sewer overflows was "likely to be a source of microplastic flushes to rivers". But, he added, "we should not ignore all sorts of run-off from roads and fields adjacent to rivers".

And water industry body Water UK said that "prevention was better than cure". "The public can play their part as well by not flushing wet wipes, and other single-use plastic items down the toilet," a spokesperson said.

Microplastics settle in the riverbed, which is the foundation of the river ecosystem, so researchers are concerned that this pollution accumulates exactly where it could do the most harm. Dr Rachel Hurley, at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research, said that the impact of microplastic pollution on rivers was a concern around the world.

"A lot of wastewater goes untreated globally," she said. "And we know this wastewater concentrates many different types of microplastic in one place."

"We need to find out what the real reasons for these wastewater discharges are."

Follow Victoria on Twitter, external

Hear more about this story on Inside Science on BBC Sounds

Related topics

- Published14 May 2021

- Published12 April 2021

- Published11 March 2021