Green light for 'net zero' equivalent for nature

- Published

A quarter of native mammals are at risk of extinction in the UK

The government has promised to "halt the decline of nature" as part of a new drive to improve the environment.

More trees are to be planted, the sale of peat will be banned and new targets will be set to return species such as wildcats and beavers to the countryside.

The measures include a legally binding 2030 target to address wildlife loss.

Environment Secretary George Eustice described the move as "a huge step forward".

In a speech from Delamere Forest, in Cheshire, he said: "We hope that this will be the net zero equivalent for nature, spurring action of the scale required to address the biodiversity crisis."

The RSPB says the UK provides crucial habitat for many birds, including the curlew

The legally binding target will apply to England only, with devolved administrations able to set their own policy.

Wildlife groups have welcomed the proposals as "an important milestone".

Richard Benwell, CEO of Wildlife and Countryside Link, a coalition of 57 nature groups, said: "If the legal detail is right, and the targets are comprehensive and science-based, then this could inspire the investment and action needed to protect and restore wildlife, after a century of decline."

Black Lake peat bog in Delamere Forest has been restored - a project that has taken 20 years

The government has also set out new proposals to protect England's peatlands as part of a drive to achieve its goal of bringing greenhouse gas emissions to zero overall - known as net zero - by 2050.

It plans to ban sales of peat compost to gardeners in England by 2024 and provide funding to restore 35,000 hectares (86,000 acres) of degraded peatlands in the next four years, about 1% of the UK's total.

Healthy peatlands play an important role in storing carbon - three times as much as forests. However, peatlands damaged by draining, planting with trees, or farming, start to leak carbon, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

Only a fifth of the UK's 2.6 million hectares (6.4 million acres) of peat are in good condition. Estimates suggest the habitat - which ranges from upland moors to rich agricultural lowland - could give off as much as 23 million tonnes of carbon emissions a year.

The Wildlife Trusts' chief executive Craig Bennett said the government's initial target to restore 35,000 hectares of peatland was disappointing and called for a commitment to restore all upland peatland and at least a quarter of lowland peat.

He said: "It's essential that we stop nature's decline and restore 30% of land and sea by 2030 - doing so will help wildlife fight back and enable repaired habitats to store carbon once more."

The Wildlife Trusts said it could be "embarrassing" for the UK - as hosts of the key climate summit in Glasgow in November - to allow carbon-rich peat to be "dug up and sold".

"Peatland is so important for carbon sequestration and for wildlife. And, currently, we're wrapping it in plastic and selling it in garden centres," said Elliot Chapman-Jones.

The government also plans to treble tree planting rates in England to 7,000 hectares of new woodland a year by 2024.

There will also be funding to provide incentives for landowners and farmers to plant and manage trees, and at least three community forests will be created.

How ambitious is the tree-planting plan?

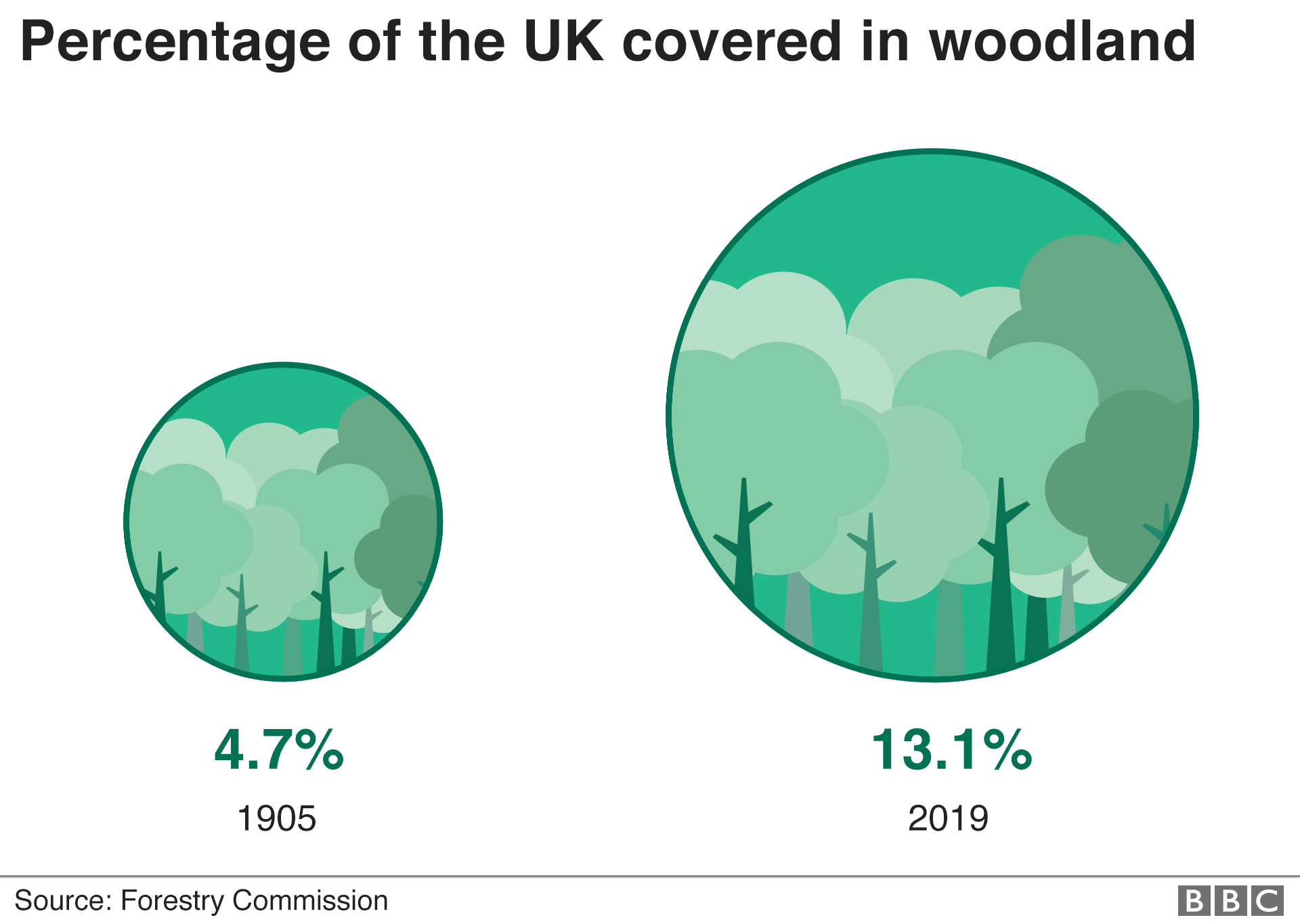

The plan to treble tree-planting rates in England by 2024 sounds like an awful lot, but it is starting from a very low level.

We've looked at previous tree planting pledges made by the various parties at the last general election. Tree planting is a devolved issue, so there are different policies across the UK.

At least three community forests will be created as part of the new England Trees Action Plan, but the government's UK-wide goal is for 30,000 hectares of trees to be planted annually by 2024.

That means most of the planting will still be of non-native trees on commercial conifer plantations in Scotland, which deliver fewer benefits for wildlife and biodiversity.

The government hopes to increase tree cover from 10% to 12% of total land area in England, and the aim is to increase the UK-wide figure to 17% by 2050 to help the country reach net zero carbon emissions.

The average tree cover across the rest of Europe is about 35% of land area. So, the UK target - and England's in particular - is actually quite modest.

Groups including the Wildlife Trusts and RSPB have campaigned to halt the ongoing decline in nature

Abi Bunker, director of conservation and external affairs at the Woodland Trust, said the UK's woodland cover had nearly tripled since 1900, but much of the increase has been low diversity forestry plantations.

"Native woods and trees are fragmented, at risk from development, and too many are in poor condition, with half of UK wildlife and plant species that depend on woodland in decline," she said.

"Government's targets for new woodland should be met by integrating UK sourced and grown native trees into our landscapes, helping to deliver for nature and people."

Related topics

- Published30 September 2020