Appeal to identify 'La Botaniste' who slipped from history

- Published

The handwritten inscription reads "Mrs Allen, La Botaniste"

When sorting through books gathering dust in the attic, it's common to find mementos of the past such as a poem, a pressed-flower, or a letter.

But when staff at the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) went through hundreds of old plant books, they stumbled on a collection of botanical treasures the likes of which they'd never seen before.

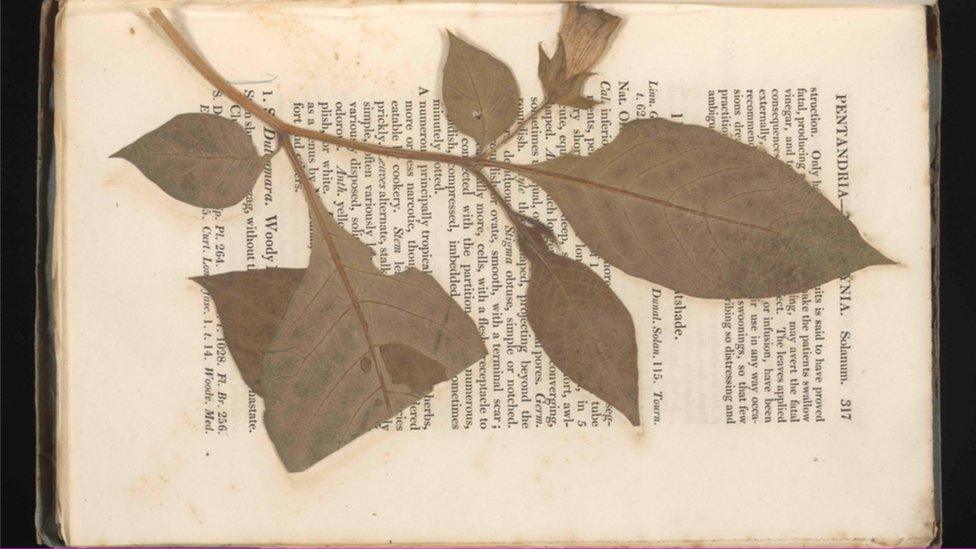

Tucked inside a copy of The English Flora from 1830 were poems, doodles, plant specimens and a cartoon.

Judging by the contents, the owner was a keen plants woman. But her name, Isabella A Allen, appears to have slipped from history.

She may be the early 19th Century botanical illustrator about which little is known. Or she could be among the legions of uncelebrated 19th Century women with a passionate interest in plants.

Either way, the RHS is hoping to track her down to find out more about her life.

"All we've got is a reasonably common name and lots of contextual stuff that she's interested in botany," says head of libraries and exhibitions, Fiona Davison.

"What I'm hoping is that somebody is aware in their family tree of an Isabella A Allen, that they've got any information about being a botanical artist or involved in botany."

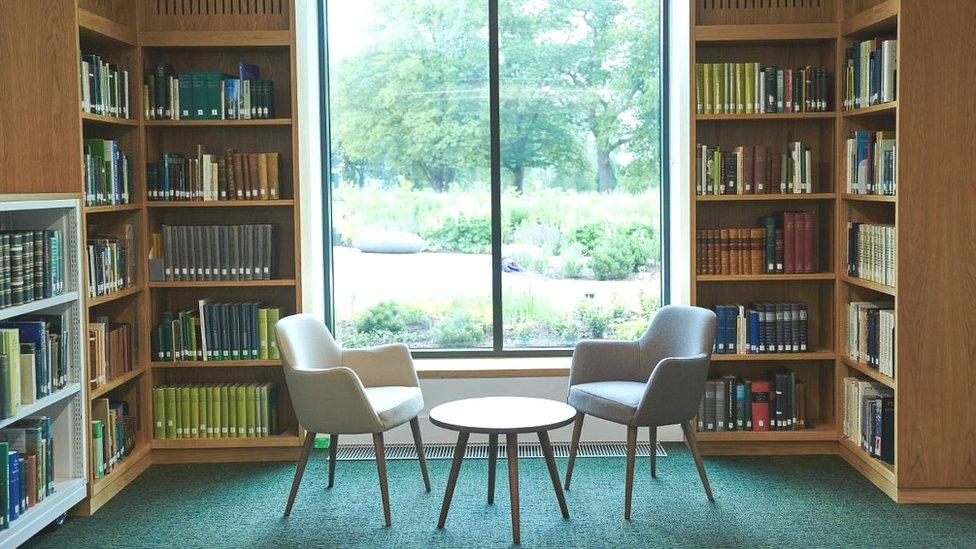

The new science centre will house botanical books and specimens

The book the unknown botanist scribbled in was by a weighty scientific author, Sir James Edward Smith, from a time when botany was a popular scientific subject for women in the higher social classes.

Botany was an area where they could make discoveries and be part of a broader scientific community. Many contributed to herbaria, the collections of preserved plants that form the cornerstone of botanical study, while others were skilled botanical artists.

"I think she clearly is a keen botanist because pressed in a number of the pages are wild flowers," says Fiona, listing kidney vetch, cranesbill, louse wort and sow thistle, among others. "They're wild flowers when you're out on a botanising trip you would have picked up, identified with the help of the book and pressed."

The woman who draws plants

It's not a rare book; the RHS alone holds many copies of the four volumes. But this was an unusual edition because it contained annotations, bookmarks and a cartoon. It came to light when staff were going through boxes of books ahead of combining their two collections within the newly built science laboratories at RHS Wisley.

"I don't think that this volume had been opened in decades. It's just been sat in an attic in Wisley," Fiona explains. "We opened this little one and we were really amazed to find all of this additional material left by its original owner."

It's not known how the book came into the hands of the RHS, meaning some detective work is required. It's safe to assume Isabella lived in the UK, but there are no hints of any geographical location such as an address.

The book has numerous wild plant specimens inserted in the pages

As well as an annotation ("this is the book of Isabella A Allen"), a print known as a personification is stuck inside. Printed and sold as sheets, they depicted people constructed of artefacts embodying their character or tools of their trade. For instance, a woman working in the potteries was fashioned from bowls, jugs and plates; while an apothecary had pill tins for feet.

The one inside Isabella's book was composed of flowers and vegetables. It was produced by a male midwife and surgeon called George Spratt, who was known for his caricatures and botanical works.

The book was a gift to Isabella Allen in 1830 from "my good friend Mrs Green". There is also a handwritten poem that appears to be an adaptation of a common work, with a reference to botanists filling a garden with Greek- and Latin-named plants. "Lovely women all unschooled and wild," Isabella writes, possibly referring to women's involvement in botany.

The RHS has made an attempt to find Isabella A Allen or Mrs Green, but there are endless women of this name on genealogy websites.

They are keen to track her down to find out more about women's contributions to botany. At the time, Linnean classification was in vogue. This system, developed by the Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus in the 1700s, was based on the similarities of the reproductive parts of a plant rather than their appearance as a whole. Plants and animals were each given two names based on their genus and species name.

"Those are very straight forward, legible, easy-to-understand ways of classifying plants and that made it very accessible to amateurs and therefore to women," says Fiona. "And it becomes a fashionable and respectable accomplishment to be botanically interested and well-educated. "

The library at RHS Hilltop contains 50,000 books and pamphlets

Botany was seen as an activity for self-improvement and a "feminine" pursuit that gave women opportunities to publish their work. Unlike other areas of natural history, plants could be collected and studied at home.

However, later in the 19th Century botany became regarded as a professional activity for specialists and experts rather than amateurs, and women's contributions to the field were belittled.

John Lindley, a botanist who served as secretary to the RHS and gave his name to their London library, was determined to make distinctions between "ladies botany" and botanical science, which he said was "an occupation for the serious thoughts of man".

Despite such efforts, women continued to participate in botany, especially by writing for other women, children, and general readers.

As for Isabella A Allen, it's hoped someone can solve the mystery of the book. "We hope that we'll be able to share it with people and show it in the new library as part of the wider effort we're making to encourage people to take an interest in the plants that are growing around them in the same way that Ms Allen did," says Fiona.

Follow Helen on Twitter., external