Then and now: Arctic sea-ice feeling the heat

- Published

In our monthly feature, Then and Now, we reveal some of the ways that planet Earth has been changing against the backdrop of a warming world. The shrinking sea-ice in the Arctic is not only a sign of climate change, it is causing the planet to warm more quickly. This is because more sunlight is being absorbed by the darker ocean, rather than being reflected back into space.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Arctic sea-ice plays an important role in controlling the planet's temperature, and any problem with this natural thermostat is a cause for concern.

Figures from the US space agency (Nasa) suggest the loss of the minimum Arctic sea-ice extent is in the region of 13.1% per decade, based on the 1981 to 2010 average.

A major report on climate change in 2007, external linked the growing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, caused by human activity, with declining sea-ice extent in the region.

The disappearance of the sea-ice in a warming world also contributes to rising average surface temperatures. The sea-ice is estimated to reflect 80% of sunlight back into space, meaning it does not warm the surface.

But when the sea-ice has melted, the darker ocean surface is exposed, which absorbs about 90% of the sunlight hitting it. This results in warming of the region.

This phenomenon is known as the Albedo effect, and it occurs because light surfaces reflect more heat than dark surfaces.

Vanishing point

The freezing and thawing of the ocean in the Arctic is a seasonal occurrence, with the freezing peaking in March and the melting reaching its maximum in September.

Data suggests that the extent of Arctic sea-ice is shrinking by 13% each decade as the world warms

However, data from on-the-ground observations and from satellites tell us that the extent of sea-ice in the Arctic polar region is declining as the planet warms.

As this occurs, the albedo (or reflectivity) is reduced, because the dark ocean waters absorb more heat than the lighter sea-ice. This in turn causes the land and oceans to warm even more.

Ultimately, scientists fear, the increasing amount of ground being exposed in regions traditionally covered with snow will trigger a "tipping point". This is where the warming of the atmosphere reaches a point where human interventions will no longer be able to halt it.

Smaller and warmer world

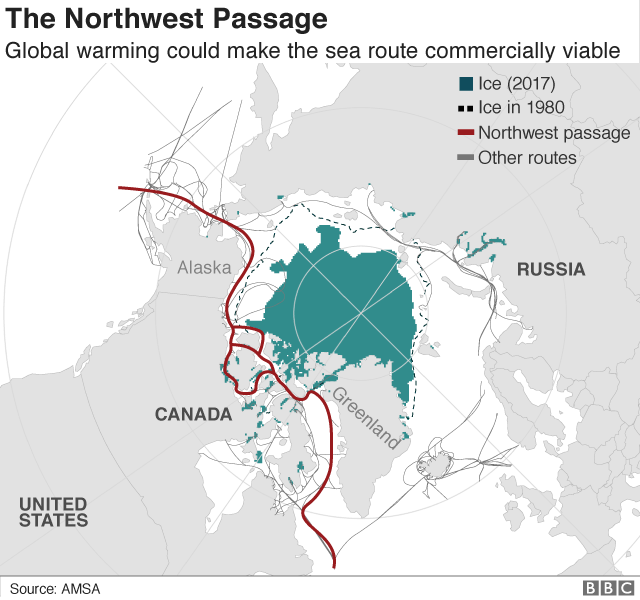

Another impact of the decreasing density of ice in the northern polar region is the opening of the Northwest Passage. This trading route links the North Atlantic Ocean with the North Pacific Ocean.

Since the 19th Century, there has been clamour to find a navigable route through frozen Arctic waters between Greenland and Canada's Arctic islands.

It has long been a deadly pursuit for mariners who braved the frozen seascape. However, some experts estimate that the route will become commercially viable in the near future as the sea-ice retreats in the summer months.

For some, it is going to revolutionise the global shipping sector. For others, it is a disaster waiting to happen.

Environmental groups fear a growing volume of shipping traffic through the pristine Arctic waters will damage slow-growing, long-lived marine ecosystems.

They particularly fear a ship encountering a mishap in the remote polar waters, resulting in a potentially devastating pollution incident.

Lack of food

Evidence suggests that the thinning sea-ice is affecting wildlife, including top-of-the-food-chain predators such as polar bears. The ice is not strong enough to support the animals' weight, forcing them to embark on energy-sapping swims and making it more difficult to catch prey.

Studies show that polar bears are struggling to hunt on the melting sea-ice during summer months

As well as causing starvation, it is also reportedly resulting in bears coming into human settlements looking for food.

Another concern among scientists is that melting sea-ice is affecting a major ocean current in the Arctic - the Beaufort Gyre.

Freshwater is less dense than salty seawater. The researchers said a sudden influx of freshwater from the Arctic Ocean into the northern Atlantic Ocean could alter the strength of the current.

This is because the force pushing water down the eastern coast of continental North America will be reduced, resulting in a smaller volume of warmer tropic waters from equatorial regions being displaced towards western Europe.

Models suggest the reduction in warmer waters heading towards western Europe will result in lower temperatures in the region. This, in turn, would also affect weather patterns in the global climate system.

Our Planet Then and Now will continue each month up to the UN climate summit in Glasgow, which is scheduled to start in November 2021