Canterbury Cathedral stained glass is among world's oldest

- Published

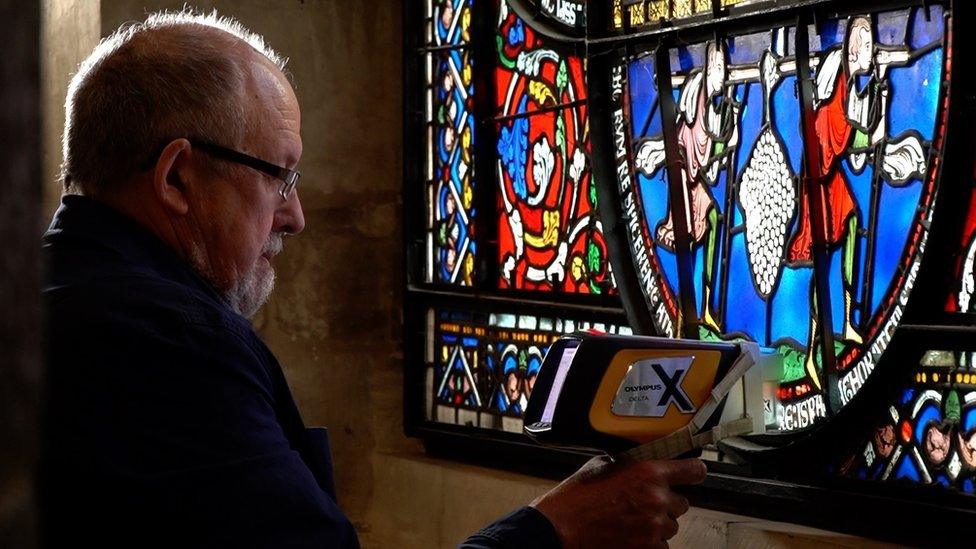

The windolyser is a hand-held device that can discover the age of the glass without damaging it

New research indicates that some stained glass windows from Canterbury Cathedral may be among the oldest in the world.

The panels, depicting the Ancestors of Christ, have been re-dated using a new, non-destructive technique.

The analysis indicates that some of them may date back to the mid-1100s.

The windows would therefore have been in place when the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, was killed at the cathedral in 1170.

Léonie Seliger, the head of stained glass conservation at the cathedral, and part of the research team, told BBC News that the discovery was historically "hugely significant".

"We have hardly anything left of the artistic legacy of that early building [apart from] a few bits of stone carving. But until now, we didn't think we had any stained glass. And it turns out that we do," she said.

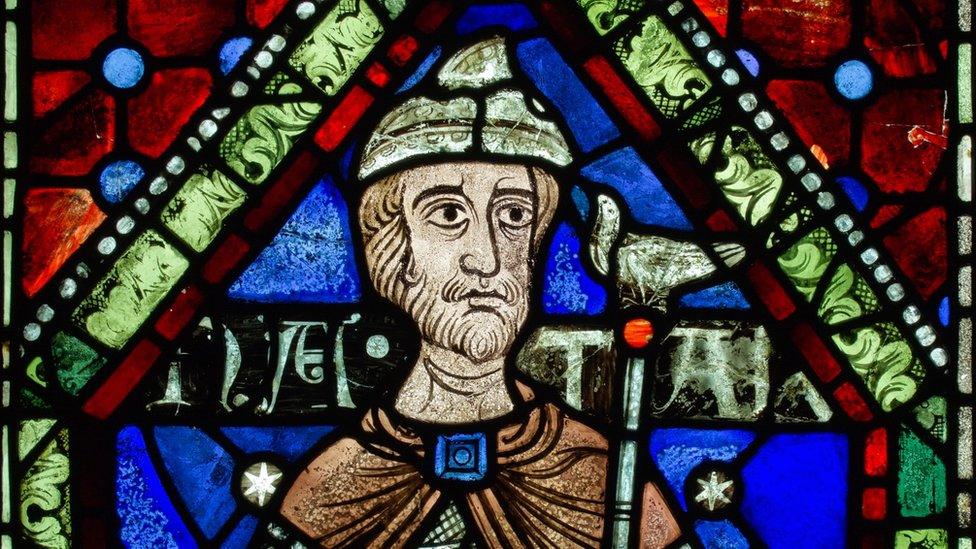

The prophet Nathan appeared stylistically different to many of the others in the Ancestors series

She said she had been so happy at hearing the news, she had been "ready to dance."

Ms Seliger added: "[The stained glass] would have witnessed the murder of Thomas Becket, they would have witnessed Henry II come on his knees begging for forgiveness, they would have witnessed the conflagration of the fire that devoured the cathedral in 1174. And then they would have witnessed all of British history."

Thomas Becket was murdered in the cathedral by four knights who believed they were acting on the orders of Henry II, with whom the archbishop had clashed. However, some historians doubt that Henry issued the command to assassinate Becket, and that his words may have been misinterpreted.

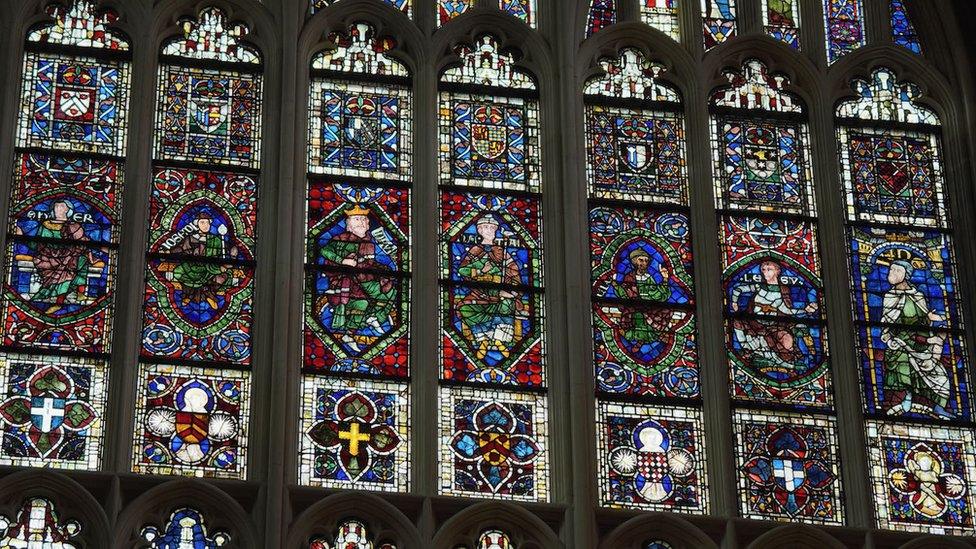

The re-dated panels are part of the Ancestors of Christ series depicted over one of the cathedral's entrances. It was thought for centuries that they were made by master craftsmen in the 13th century.

The art historian Prof Madeline Caviness suggested in the 1980s that some of the panels were earlier than previously believed because they were stylistically different. That suspicion has now been confirmed by a team of researchers from University College London (UCL), who built a device called a "windolyser" to solve the mystery.

It can be used on location and doesn't damage the glass. It shines a beam on to the surface - which causes the material in the glass to radiate. This radiation contains the glass's chemical fingerprint - from which the researchers were able to work out its age. Astronomers use the same technique, called spectrometry, to discover the chemical composition of distant stars.

Dr Laura Ware Adlington, who led the research, said that the windolyser's results were "very exciting".

"These findings will make us all, from art historians and scientists, to members of the public visiting the cathedral, look at the Canterbury stained glass in a whole new light."

Prof Caviness said she was ''delighted'' to hear that her assessment had been confirmed by Dr Ware Adlington.

''The scientific findings, the observations and the chronology of the cathedral itself all fit together very nicely now,'' she told BBC News. Prof Caviness, who is now 83, told me that the finding had jolted her out of a ''Covid numbness'' that she had been feeling.

''I wish I was younger and could throw myself more into helping Laura with her future work. But I've certainly got a few more projects to feed her.''

Dr Ware Adlington's study suggests that some of the Canterbury Ancestors may date back to the back to the period between 1130-1160, at least 10 years before Thomas Becket's infamous killing at the site in 1170.

Canterbury Cathedral is a symbol of England's history, artistry and religious thinking. Now, a scientific discovery has given us a new perspective on the nation's past.

And it is also thought that three other stylistically distinct windows in the cathedral may also be from an earlier time than originally thought.

The "Ancestors Series" was created for the cathedral beginning in the late 12th century, as part of a rebuilding programme which took place after a devastating fire in 1174. And the installation of the windows continued from the late 1170s through until 1220.

The new dating suggests that the panels had been present in the choir of the earlier building and survived the fire. It is now thought that they were stored for future use and later adapted for the new building.

Prof Ian Freestone, from the UCL Institute of Archaeology, described the research as a "detective story".

"We've been working on it for some time, putting all the pieces in place. And then we finally get an answer something new, that brings together science and art into one story," he said.

Follow Pallab on Twitter, external.