Covid origins: Scientists weigh up evidence over virus's origins

- Published

There is a "strong association" between the early outbreak and the sale of live animals in a market, scientists say

Amid the misery of a pandemic that has claimed at least four million lives, the scientific search for its origins has itself become toxic.

While it is now hideously ubiquitous, Covid-19 is still only an 18-month-old disease. And the search for its start was officially set in motion in 2020 by a World Health Organization investigative team.

Questions over its conclusions have escalated into a heavily politicised feud. Some research scientists, who have tried to unpick the pandemic's origins, have been accused of conspiracy and cover-up - based on no evidence.

Now, 21 researchers - all seeking to understand how a virus that originated in bats transferred into humans - aim to "set the record straight" by publishing their summary of the scientific evidence about the pandemic's beginning., external

"It's not true that we don't know where it came from - we just don't know how it got into humans," says Glasgow University virologist Prof David Robertson.

It is widely accepted that an ancestor of the virus originally circulated harmlessly in wild bats. But it is vital to discover how, where and exactly when that first made its way into a person to prevent a similar future outbreak.

There is no definitive piece of evidence - no Covid-positive bat or a confirmed first human case - to show conclusively how it started. That may never be known, but the scientists who wrote this latest report want to clarify the available evidence and what it means.

Similar to the Ebola outbreak, the coronavirus's 'ancestor' is believed to have been a disease carried by wild bats

They have published what is called a pre-print, meaning it has not yet been reviewed and edited by other experts. And its key conclusion, says Prof Robertson, is that this virus's biological properties closely match viruses that have been found in nature - in bats.

This outbreak, he adds, looks very much like the emergence of the first Sars back in 2003.

In that case, the virus was isolated in a widely-traded animal called a palm civet. Over the next few years researchers discovered very closely related viruses in bats, and in 2017, the ancestor of the Sars virus was found in a population of horseshoe bats in southern China., external

The outbreak was essentially tracked and traced back to the wild animal it came from - deadly mystery solved.

"The only difference [with Covid] is that we've not found the intermediate species this time," Prof Robertson says.

"But the bat virus link and the strong association to markets selling live animals are both there."

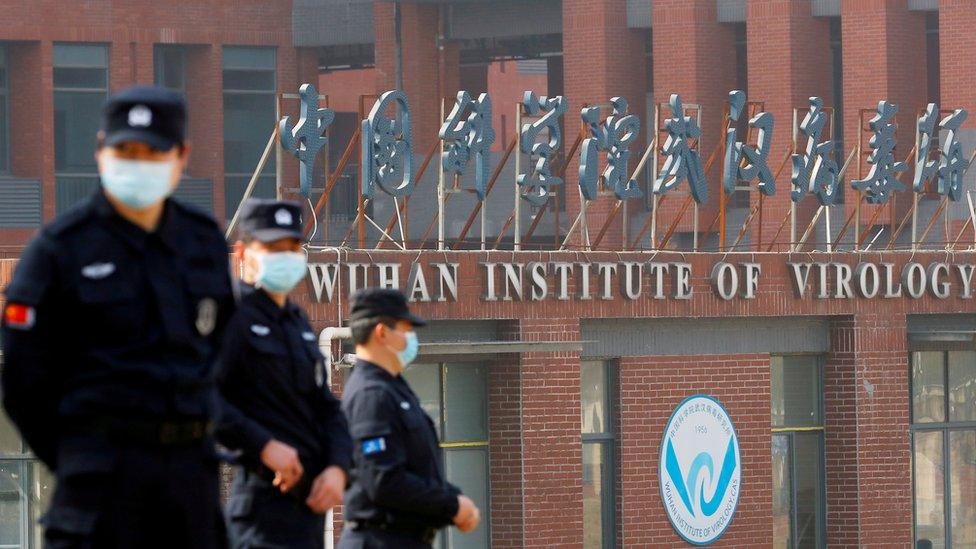

Lab-leak theories centre on the Wuhan Institute of Virology

Crowded, unhygienic live animal markets, many scientists agree, provide an ideal transmission hotspot for new diseases to "spill over" from animals. And in the 18 months up to the beginning of the pandemic, a study showed that nearly 50,000 animals - of 38 different species - were sold at markets in Wuhan.

The researchers say that a natural spillover - probably linked to that animal trade - is by far the most likely Covid origin scenario.

The WHO team that visited Wuhan drew similar conclusions, external. But its apparent dismissal of the possibility the virus might have leaked accidentally from a laboratory stirred dissent among some scientists.

The laboratory under scrutiny is the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which has studied coronaviruses in bats for more than a decade.

The authors of this new report point out that none of those were, or could have been, manipulated to become Sars-Cov-2. But some scientists do not entirely accept that conclusion, including Prof David Relman, of the US's Stanford University.

"I see this [new report] as a deliberate effort to marshal all the possible information in support of what is a perfectly good hypothesis - natural spillover - but [it's] not balanced and objective," he told BBC News.

Prof Relman was one of the authors of a letter to the high-profile scientific journal, Science,, external in which senior scientists questioned the WHO report's conclusions and asked for a more thorough investigation into the so-called lab leak hypothesis.

Scientists often disagree with each other - that is part of the scientific process. And publishing evidence-based opinions in scientific journals is the platform for that evidence-based disagreement.

But the "lab leak v natural spillover" debate has moved beyond robust scientific disagreement.

In February 2020, Peter Daszak, who led the WHO investigation, was accused of silencing any debate over the possibility of a lab leak when he and 26 co-authors issued a statement in the Lancet, external medical journal stating: "We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that Covid-19 does not have a natural origin."

And many simply did not trust the information that Chinese authorities provided to the WHO investigative team.

President Biden asked intelligence agencies to report back to him within 90 days on the virus's origin

More than a year later, US President Joe Biden ordered his own intelligence agency to "redouble" efforts to investigate Sars-Cov-2's origins, including the theory that it came from a laboratory.

Around that time, some scientists who had publicly dismissed the lab leak scenario came under attack, particularly on social media.

One who has worked on Sars-Cov-2's evolutionary origins since the pandemic's early days says the evidence points to a natural spillover. He told me he considered leaving his field of research because the abuse had become so bad.

The researcher, who did not want to be identified because they feared further harassment, said: "I've had email hacks, emails that attempt to entrap me, and claims that I've faked data and am part of some sort of a systemic cover-up. And others have had it far, far worse.

"All of this takes a toll and makes you question your worth."

While the arguments have escalated over the past year, there has been no new scientific evidence pointing to a laboratory leak. And significantly, scientists almost all agree that a robust search for evidence of Sars-Cov-2's origins is the only positive way forward.

Scientists believe another pandemic will happen during our lifetime

"What we don't need right now is for scientists to insist on their favourite explanation in the absence of new, solid data," says Prof Relman.

"Sars-Cov-2 has not been found in any natural animal host. Let's just cool it and demand a proper investigation."

Prof Stuart Neil, from King's College London, a co-author of the new report, points out that demands will not necessarily lead to the conclusion for which everyone is searching.

"We're going to need co-operation from the Chinese authorities," he said. "And they need to be far more forthcoming about what they know about the early epidemic in Wuhan at the tail end of 2019.

"Only that will shed light on how the virus arrived in Wuhan, and where it was before that. This is the second major bat coronavirus zoonosis in China in 20 years, and if we don't get this straight it will happen again."

Follow Victoria on Twitter, external

Related topics

- Published6 June 2020

- Published16 February 2021