Climate change: Five things we have learned from the IPCC report

- Published

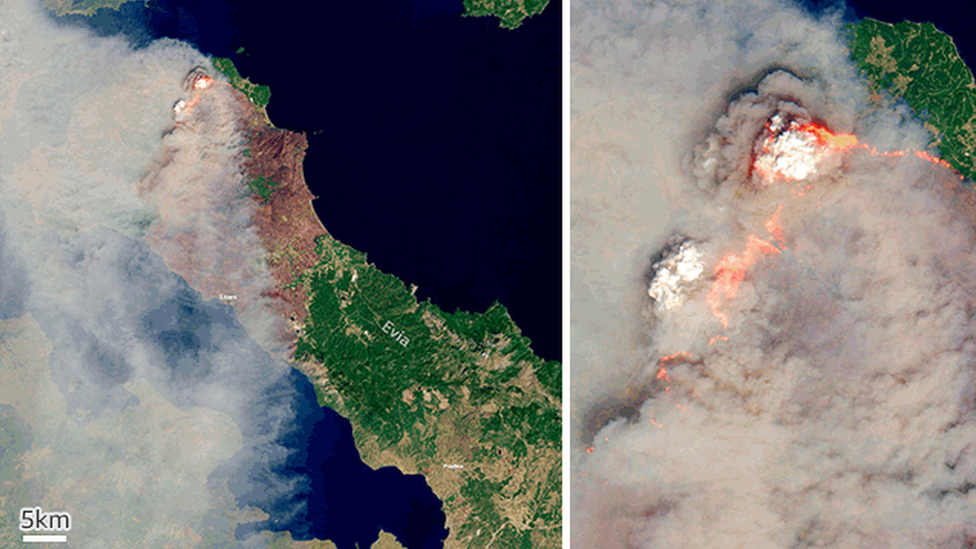

Satellite images of wildfires in Evia, Greece

The UN report on the science of climate change is set to make a huge impact. Our environment correspondent Matt McGrath considers some of the key lessons from it.

Climate change is widespread, rapid and intensifying - and it's down to us

For those who live in the West, the dangers of warming our planet are no longer something distant, impacting people in faraway places.

"Climate change is not a problem of the future, it's here and now and affecting every region in the world," said Dr Friederike Otto from the University of Oxford, and one of the many authors on the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

It is the confidence of the assertions that the scientists are now making that is the real strength of this new publication.

The phrase "very likely" appears 42 times in the 40-odd pages of the Summary for Policymakers. In scientific terms, that's 90-100% certain that something is real.

"I think there's not one single kind of new surprise that comes out, it's the over-arching solidness that makes this the strongest IPCC report ever made," Prof Arthur Petersen, from University College London (UCL), told BBC News.

Prof Petersen is a former Dutch government representative at the IPCC, and was an observer at the approval session that produced this report.

"It's understated, it's cool, it's not accusing, it's just bang, bang, bang, one clear point after the other."

The clearest of these points is about the responsibility of humanity for climate change.

There's no longer any equivocating - it's us.

More than 100 people were killed in floods that ravaged parts of Europe in July 2021

The 1.5C temperature limit is on life support

When the last IPCC report on the science of climate change was published in 2013, the idea of 1.5C being the safe global limit for warming was barely considered.

But in the political negotiations leading up to the Paris climate agreement in 2015, many developing countries and island states pushed for this lower temperature limit, arguing that it was a matter of survival for them.

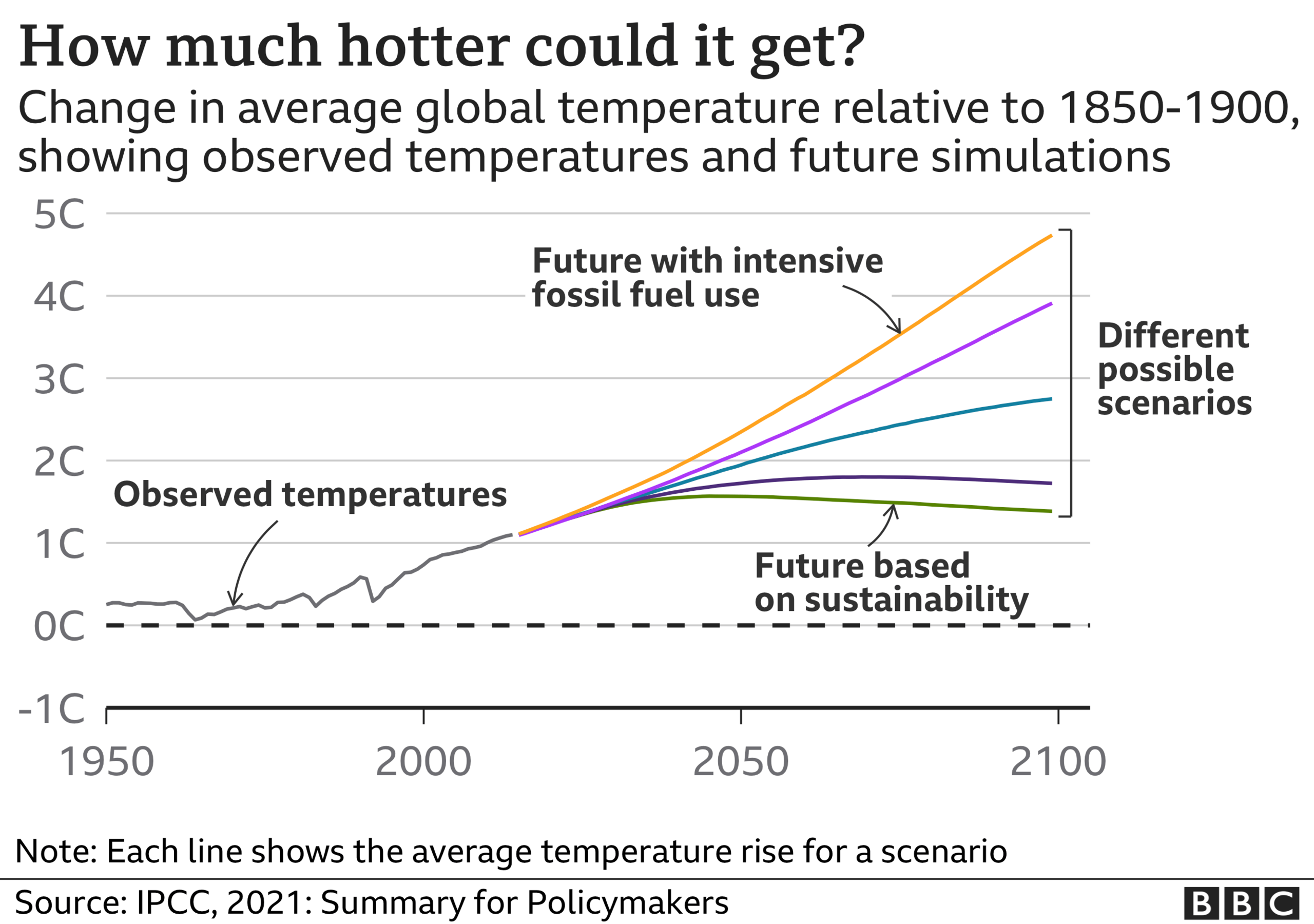

A special report on 1.5C in 2018 showed the advantages of staying under the limit were massive compared to a 2C world. Getting there would require carbon emissions to be cut in half, essentially, by 2030 and net zero emissions reached by 2050. Otherwise, the limit would be reached between 2030 and 2052.

This new report re-affirms this finding. Under all scenarios, the threshold is reached by 2040. If emissions aren't reined in, 1.5C could be gone in around a decade.

Abandoned canoes on the cracked, dried up shores of Lake Chilwa, Malawi

Reaching net zero involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible using clean technology, then absorbing any remaining ones by, for example, planting trees.

While the situation is very serious, it is not a sudden drop into calamity.

"The 1.5C threshold is an important threshold politically, of course, but from a climatic point of view, it is not a cliff edge - that once we go over 1.5C, suddenly everything will become very catastrophic," explained Dr Amanda Maycock, from the University of Leeds, and one of the authors of the new report.

"The very lowest emissions scenario that we assess in this report shows that the warming level does stabilise around or below 1.5C later on in the century. If that were the pathway that we would follow, then the the impacts would be significantly avoided."

The bad news: No matter what we do, the seas will continue to rise

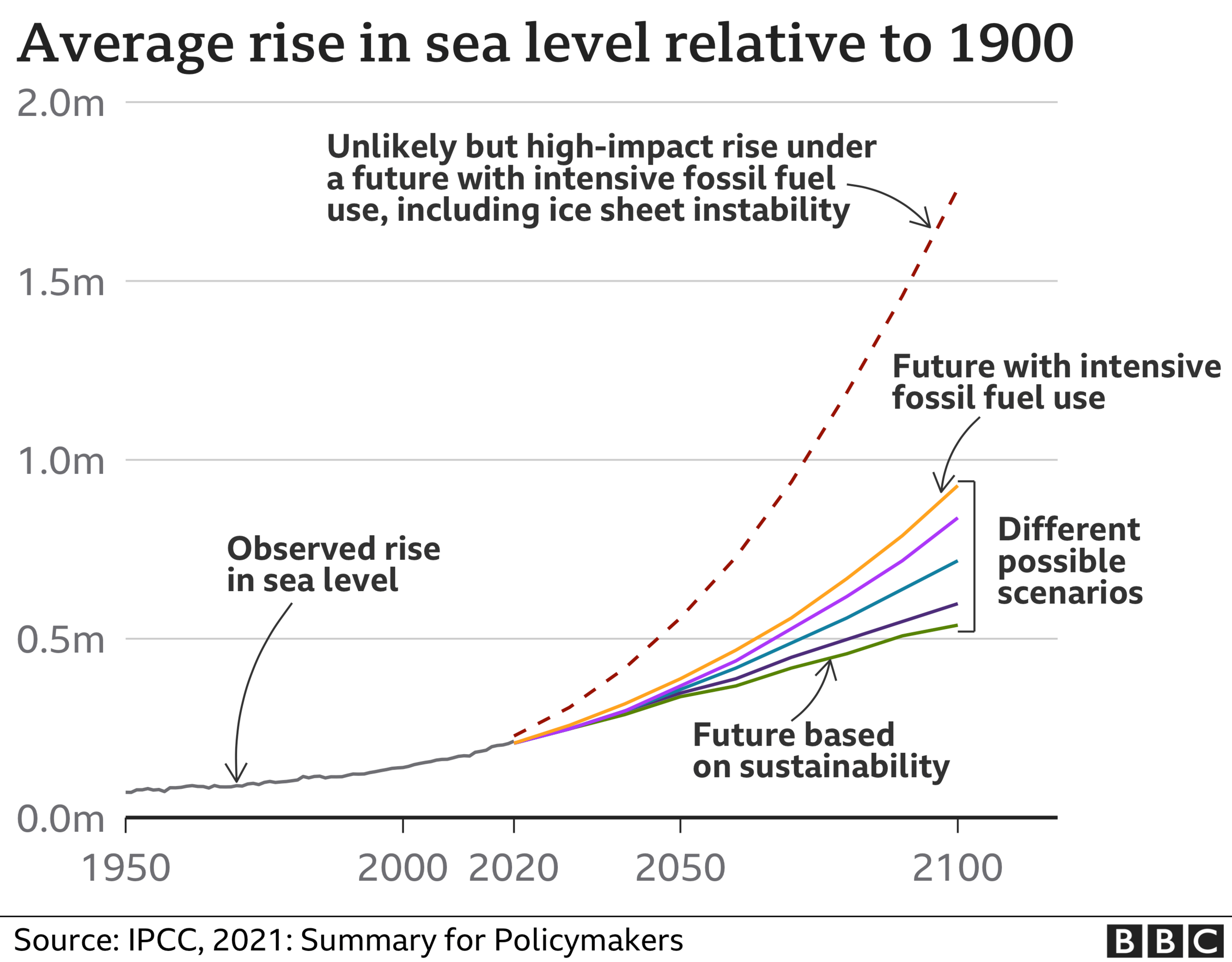

In the past, the IPCC has been criticised for being way too conservative when it came to assessing the risk of sea-level rise. A lack of clear research saw previous reports exclude the potential impacts of the melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

Not this time.

The report shows that under current scenarios, the seas could rise above the likely range, going up to 2m by the end of this century and up to 5m by 2150. While these are unlikely figures, they can't be ruled out under a very high greenhouse gas emissions scenario.

That's bad enough - but even if we get a handle on emissions and keep temperatures around 1.5C by 2100, the waters will continue to rise long into the future.

"The gorilla that looms large in the background is these very scary sea-level rise numbers in the long term," said Prof Malte Meinshausen from the University of Melbourne and an IPCC author.

"In the paper it shows that even with 1.5C warming we're looking at the long-term of two to three metres. And under the highest scenarios, we could be looking at multi-metre sea-level rise by 2150. That is just scary, because it's maybe not at the end of our lifetime, but it is around the corner and it will be committing this planet to a big legacy."

Even if the sea-level rise is relatively mild, it will have knock-on effects that we cannot avoid.

"With gradual sea-level rise, those extreme sea-level events that have occurred in the past, just once per century, will occur more and more frequently in the future," said Valérie Masson-Delmotte, co-chair of the IPCC working group that prepared the new report.

"Those that occurred only once per century in the past are expected to occur once or twice per decade by mid-century. The information we provide in this report is extremely important to take into account and prepare for these events."

The good news: Scientists are more certain about what will work

The warnings are clearer and more dire - but there is an important thread of hope running through this report.

Scientists have long been worried that the climate could be more sensitive to carbon dioxide than they thought.

They use a phrase - equilibrium climate sensitivity - to capture the range of warming that could occur if CO2 levels were doubled.

An infrared camera captures what appears to be methane escaping from a natural gas facility

In the last report, in 2013, this ranged from 1.5C to 4.5C, with no best estimate.

This time round, the range has narrowed and the authors opt for 3C as their most likely figure.

Why is this important?

"We are now able to constrain that with a good degree of certainty and then we employ that to really make far more accurate predictions," said Prof Piers Forster from the University of Leeds, and an author on the report.

"So, that way, we know that net zero will really deliver."

Another big surprise in the report is the role of methane, another warming gas.

According to the IPCC, around 0.3C of the 1.1C that the world has already warmed by comes from methane.

Tackling those emissions, from the oil and gas industry, agriculture and rice cultivation, could be a big win in the short-term.

"The report quashes any remaining debate about the urgent need to slash methane pollution, especially from sectors such as oil and gas, where the available reductions are fastest and cheapest," said Fred Krupp, from the US Environmental Defense Fund.

"When it comes to our overheating planet, every fraction of a degree matters - and there is no faster, more achievable way to slow the rate of warming than by cutting human-caused methane emissions."

Politicians will be nervous, the courts will be busy

The timing of this report, coming just a couple of months before the critical COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, means that it will likely be the bedrock of the negotiations. The IPCC has some form here: their previous assessment in 2013 and 2014 paved the way for the Paris climate agreement.

This new study is far stronger, clearer and more confident about what will happen if politicians don't act.

If they don't act quickly enough and COP26 ends in an unsatisfactory fudge, then the courts might become more involved.

In recent years, in Ireland and the Netherlands, environmental campaigners have successfully gone to court to force governments and companies to act on the science of climate change.

"We're not going to let this report be shelved by further inaction. Instead, we'll be taking it with us to the courts," said Kaisa Kosonen, senior political adviser at Greenpeace Nordic.

"By strengthening the scientific evidence between human emissions and extreme weather, the IPCC has provided new, powerful means for everyone everywhere to hold the fossil fuel industry and governments directly responsible for the climate emergency.

"One only needs to look at the recent court victory secured by NGOs against Shell to realise how powerful IPCC science can be."

Follow Matt on Twitter., external