COP26: What do the poorest countries want from climate summit?

- Published

Developing countries are the most vulnerable to the damage caused by climate change, such as floods, droughts and wildfires.

Addressing the needs of less wealthy and smaller countries is vital for the COP26 climate negotiations in Glasgow, where leaders are being asked to agree on new commitments to tackle climate change.

What do developing countries want?

The least developed countries have set out their priorities, external for negotiations. They want richer and developed countries to:

fulfil a pledge to provide $100bn (roughly equivalent to £73bn at current exchange rates) each year in finance to help reduce emissions and adapt to climate change

agree to net-zero targets on greenhouse gases well before 2050, with specific targets for major emitters such as the US, Australia and countries in the EU

acknowledge the loss and damage they have experienced, such as the effects of rising sea levels or frequent flooding

finalise rules on how countries will implement previous agreements

There is deep frustration among the leaders of developing nations that the richest in the world have not met their previous commitments.

Kenya's president Uhuru Kenyatta said: "Before making new pledges, start by fulfilling the existing ones."

What is Climate Justice?

Which countries are most at risk from the effects of climate change?

Developing countries have historically contributed a very small proportion of the damaging emissions that drive climate change - and currently the richest 1% of the global population account for more than twice the combined emissions of the poorest 50%., external

These poorer countries are also more vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather because they are generally more dependent on the natural environment for food and jobs, and have less money to spend on mitigation.

Over the last 50 years, more than two out of three deaths caused by extreme weather — including droughts, wildfire and floods — occurred in the 47 least developed countries., external

Countries such as Bangladesh have been on the front line of the effects of global warming

What are the richer countries doing to address the situation?

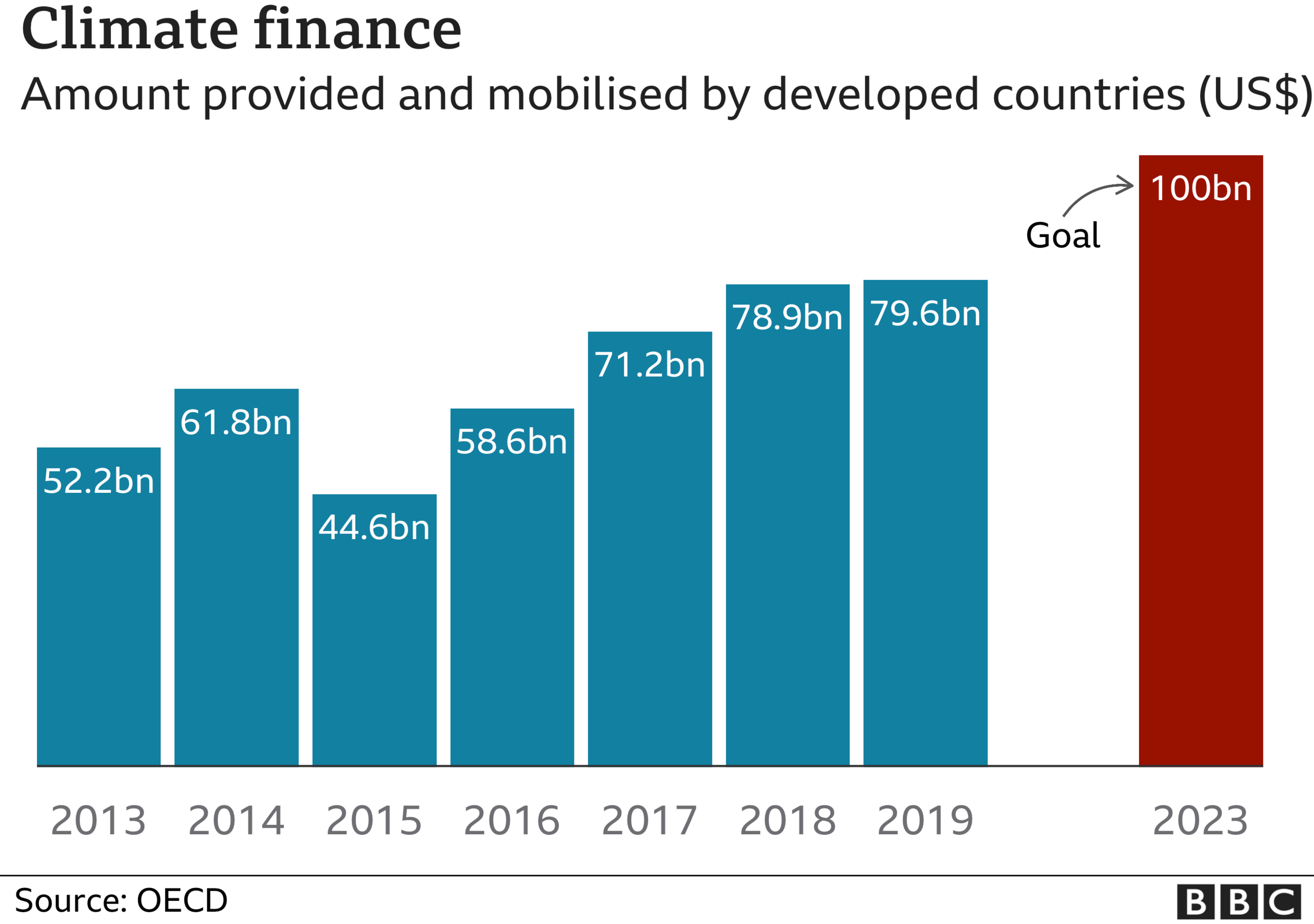

In 2009, richer countries committed to finding $100bn a year by 2020 from public and private sources, to address the needs of developing countries.

The money is to help pay for measures to reduce dangerous emissions and protect from the effects of extreme weather, such as better flood defence systems and investment in renewable energy sources.

However, total commitments had only reached $80bn by 2019, and the $100bn target is now unlikely to be met before 2023.

Securing an agreement on how to meet the commitments to developing countries - and potentially go further - is crucial if the world is going to achieve its aim to keep global temperature rises below 1.5C.

Arriving in Glasgow for the summit, Malawi's president Lazarus Chakwera said: "It's not a charity act. So pay up or perish with us."

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has put reaching $100bn as one of his four priorities for the negotiations in Glasgow.

He said that richer nations had "reaped the benefits of untrammelled pollution for generations, often at the expense of developing countries", and that they have a "duty" to support developing nations with technology, expertise and money., external

What are the obstacles for smaller countries attending the summit?

"We are negotiating for our survival," says Tagaloa Cooper, of the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme - an organisation made of up members from Pacific island countries and territories.

Rising sea levels make some of these island nations the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, but Ms Cooper says a lack of resources means they don't have the "luxury" of sending large delegations.

"Some of our most vulnerable will struggle to have a voice, and be heard, in these negotiations."

More than 120 world leaders are expected to descend on Glasgow for climate negotiations

Navigating Covid-safe travel to the Glasgow conference has been an obstacle for many delegations, particularly the Pacific islands, where infection rates have remained low during the pandemic.

Only four Pacific island heads of state are reported to be travelling to the summit,, external with others being represented by smaller teams and ambassadors.

Negotiators staying behind and participating remotely may be disadvantaged by unreliable internet access and time differences. Samoa, for instance, is 13 hours ahead of the UK.

How do developing countries negotiate at climate conferences?

Developing countries usually have less of a voice on the international stage, so it helps to form groups or blocks to amplify their cause.

The Least Developed Countries group, external is a 46-nation bloc that includes Senegal, Bangladesh and Yemen and represents one billion people.

These countries can create stronger negotiating positions when "priorities and interests are aligned", says Sonam Wangdi, the current chairman, from Bhutan.

"This crisis isn't being treated like a crisis. That has to change here in Glasgow," he says.

Bhutan has committed to keeping at least 60% of the country under forest cover

If there is to be a final agreement, all 197 UN member states that are signed up to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change have to sign.

That means the final agreement must be acceptable to both richer and developing countries.

World leaders failed to secure a legally binding agreement in Copenhagen in 2009,, external partly because a handful of developing countries including Sudan and Tuvalu opposed the final agreement.

Additional research by Esme Stallard.

Top image from Getty Images. Climate stripes visualisation courtesy of Prof Ed Hawkins and University of Reading.