James Webb: Hubble telescope successor faces 'two weeks of terror'

- Published

So much could go wrong, but the engineering teams believe they have all eventualities covered

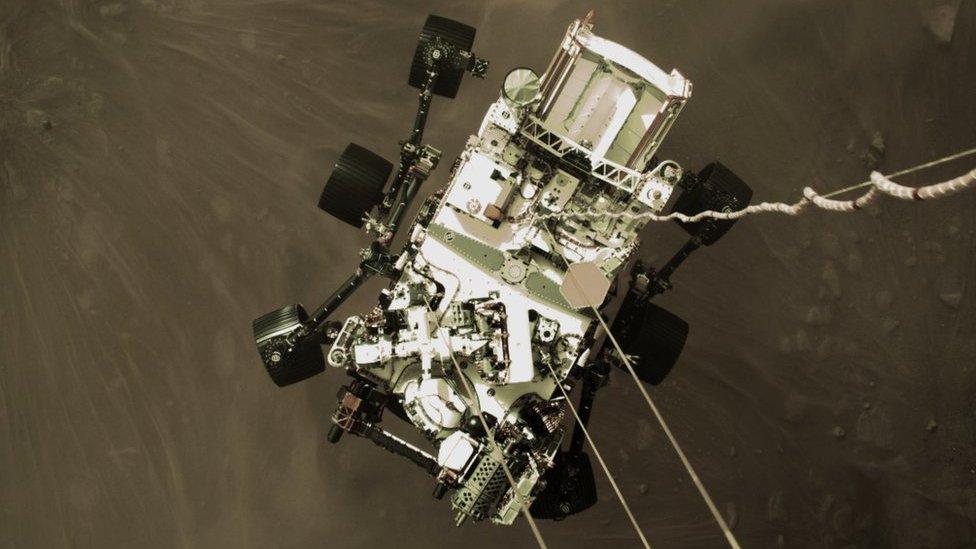

Engineers like to describe the process of landing a rover on Mars as the "seven minutes of terror".

That's how long it takes for a robot to come to a standing-stop at the surface of the Red Planet after entering the atmosphere faster than a rifle bullet; and so much has to go right in-between to avoid smashing into the ground.

But when it comes to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), it's more like "two weeks of terror".

The successor observatory to the mighty Hubble telescope has been built to see the very first stars to shine in the Universe.

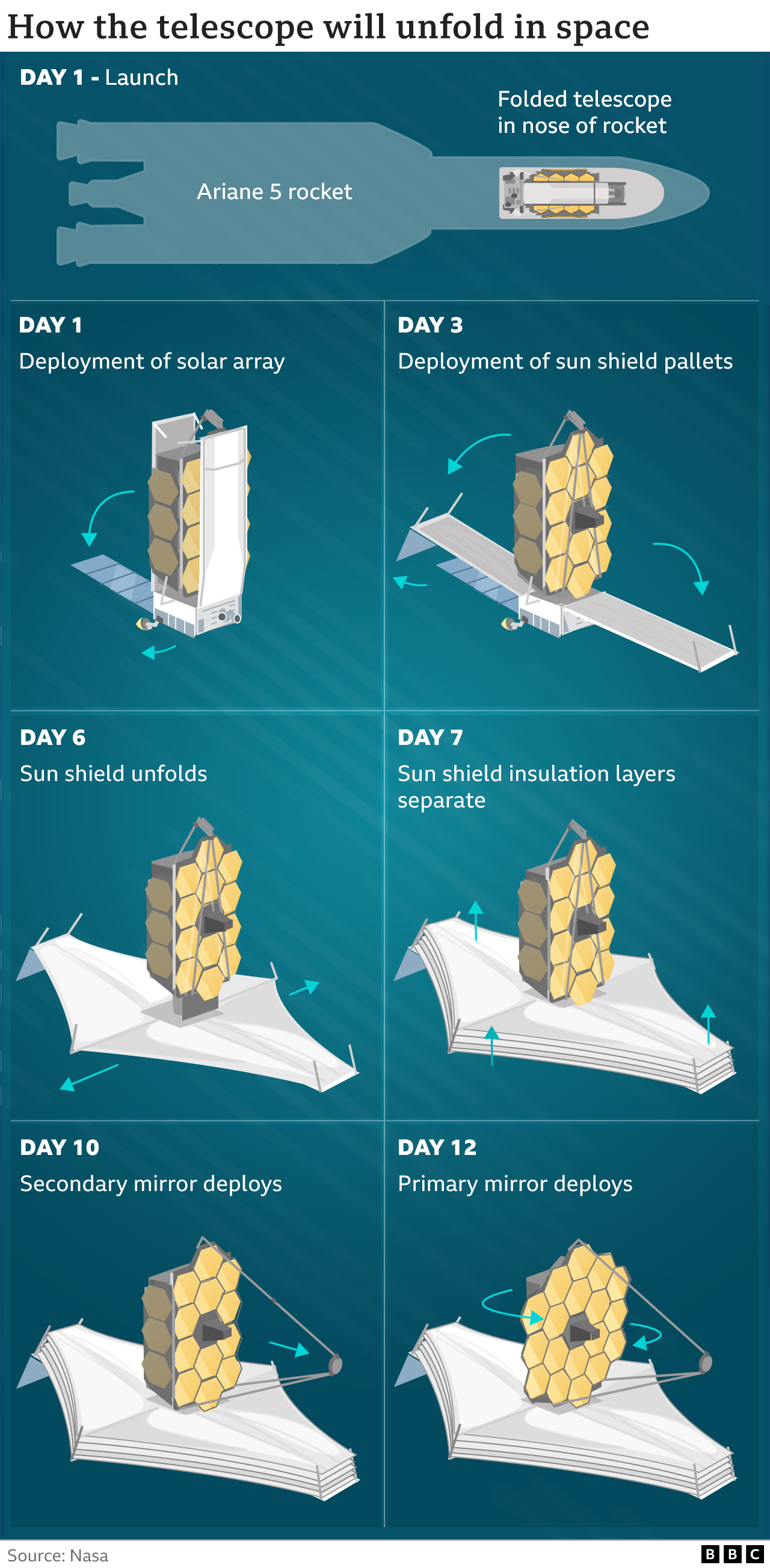

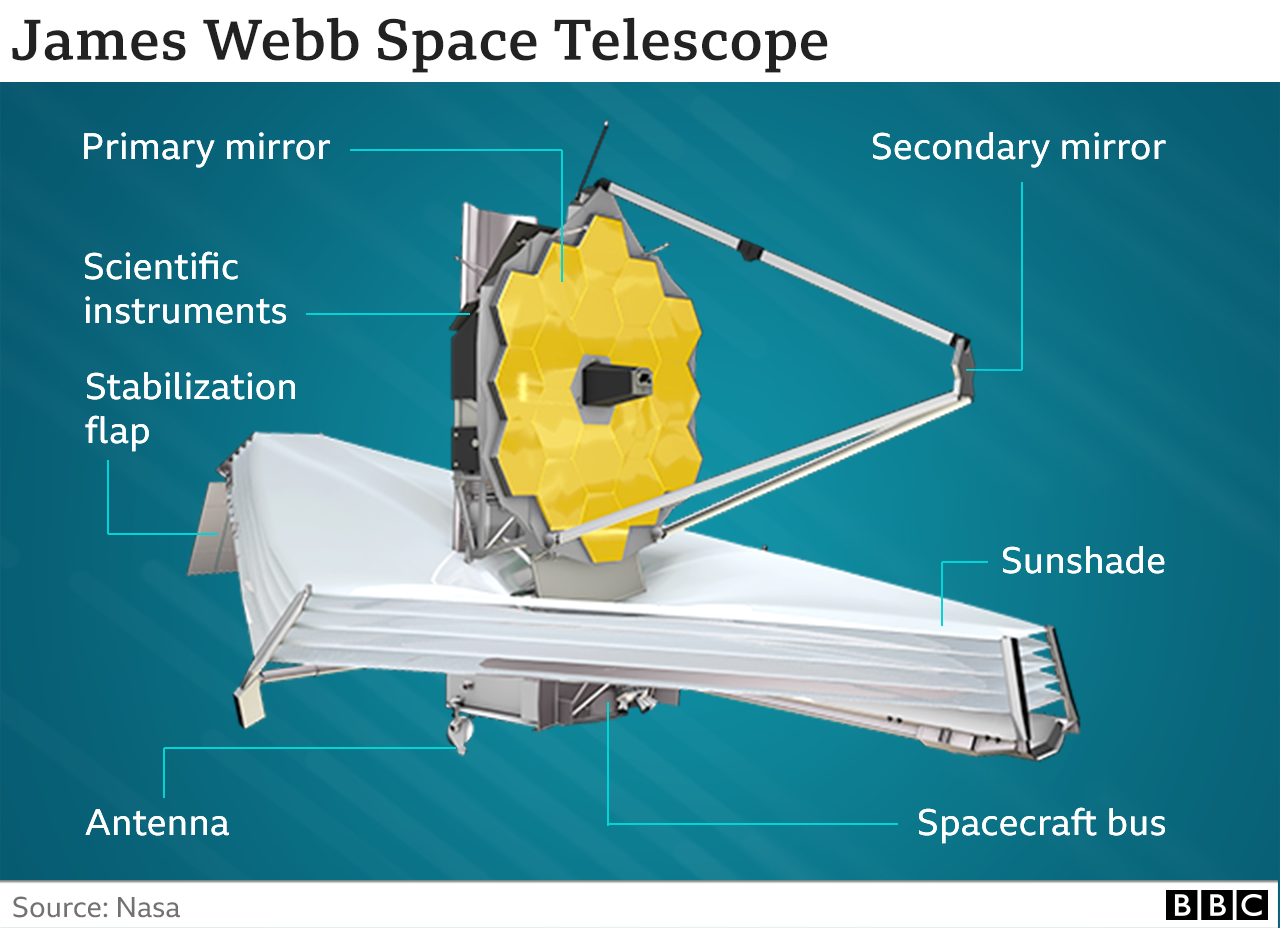

These very faint, very distant targets require a huge telescope design, one that is so big it has to be folded to fit inside its launch rocket, and then, once in orbit, unfolded again to begin taking pictures of the cosmos.

This unfurling has been called an origami exercise in reverse, where the delicate figure is the size of a tennis court.

The heart-stopper will be the five layers of super-thin membrane that make up the sunshield

It all takes place over a period of about 14 days, immediately after the launch in mid-December.

It will involve an astonishing symphony of hinges, motors, gears, springs, pulleys and cables - all of which must work on command and to perfection.

There are no fewer than 344 "single point failures" - critical moments in the timeline where, if the action doesn't occur on cue, the six-tonne telescope cannot achieve the desired configuration, fatally undermining its $10bn mission.

The expansion of the five super-thin membranes that will shield Webb's vision from interfering sunlight look particularly tricky. Heart-stopping, to be honest. But there is a quiet confidence in the engineering teams, led by the US space agency (Nasa) and aerospace manufacturer Northrop Grumman (NG). And that's because they've tested and rehearsed everything, over and over and over again.

"The sunshield is like a skydiver's parachute; it needs to be folded perfectly so that it unfolds and deploys perfectly without snags, without any tangles," said Northrop Grumman systems engineer Krystal Puga.

"To perfect the sequence, we performed multiple deployment testing over several years on both small and full-size models. We practised not only the deployment but also the stowing process. This gives us the confidence that Webb is going to deploy successfully."

Nasa's Perseverance rover touches down: Landing a robot on Mars is hard enough

Webb's drama begins almost as soon as the telescope comes off the top of its European Ariane rocket.

First, the solar array must come out. No power, no mission. Then, the high-gain antenna makes its move, enabling two-way communications with the ground. No comms, no commands.

But all that's kind of easy compared with what comes next.

Day 1 - Soon after launch, Webb puts out its solar array and its communications antenna

Day 3 - Two pallets holding the sunshield membranes open outwards. The long axis is 21m in length

Day 6 - The sunshield system is stretched out to make a diamond shape that's just over 14m wide

Day 7 - The shield's five layers separate. They will help cool the telescope as well as shade it

Day 10 - Webb is a reflecting telescope with a secondary mirror whose booms must lock into place

Day 12 - The primary mirror, built to be 6.5m across, begins the process of extending its wings

"When I started in this business about 40 years ago, I remember one of the first lessons I got taught was to avoid deployments on orbit," said Mike Menzel, Nasa's lead mission systems engineer on the project.

"James Webb cannot avoid the deployments. In fact, James Webb has to perform some of the most complex deployment sequences ever attempted, and these come with many challenges."

What if something goes awry?

There are no cameras to show what's occurring when the mechanisms are doing their thing. Part of the reasoning for omitting them is that they wouldn't be much use anyway in the dark shadow that's supposed to be cast by the sunshield.

So the teams will be relying on sensor feedback, and if a problem arises, they'll work through their "fault trees" until a solution is found.

In extremis, it's possible even to give the telescope a bit of a shake to free a mechanism that might have become stuck.

"When I say, for instance, shimmy, you're rocking the observatory back and forth," explained Alphonso Stewart, Nasa's Webb deployment systems lead.

"In terms of a twirl, we basically can spin the observatory about any given axis. And for fire and ice, we can orient the observatory in such a way to put the sun on certain areas to heat them up, if we deem that that's necessary for the deployment," he told BBC News.

Webb is currently in its stowed configuration awaiting launch on a European Ariane-5 rocket

Webb is due to enter service about 180 days after launch, a time period that includes tuning the performance of the telescope's mirrors and instruments. But the engineers will not rush their tasks, especially if they come up against a snag.

"I've been the Webb project manager for almost 11 years, and this team does not give up," said Bill Ochs.

"So, we don't talk about what do we do if we fail? We talk about how we correct problems that we see on orbit, and how we move forward from there."