Russian anti-satellite missile test draws condemnation

- Published

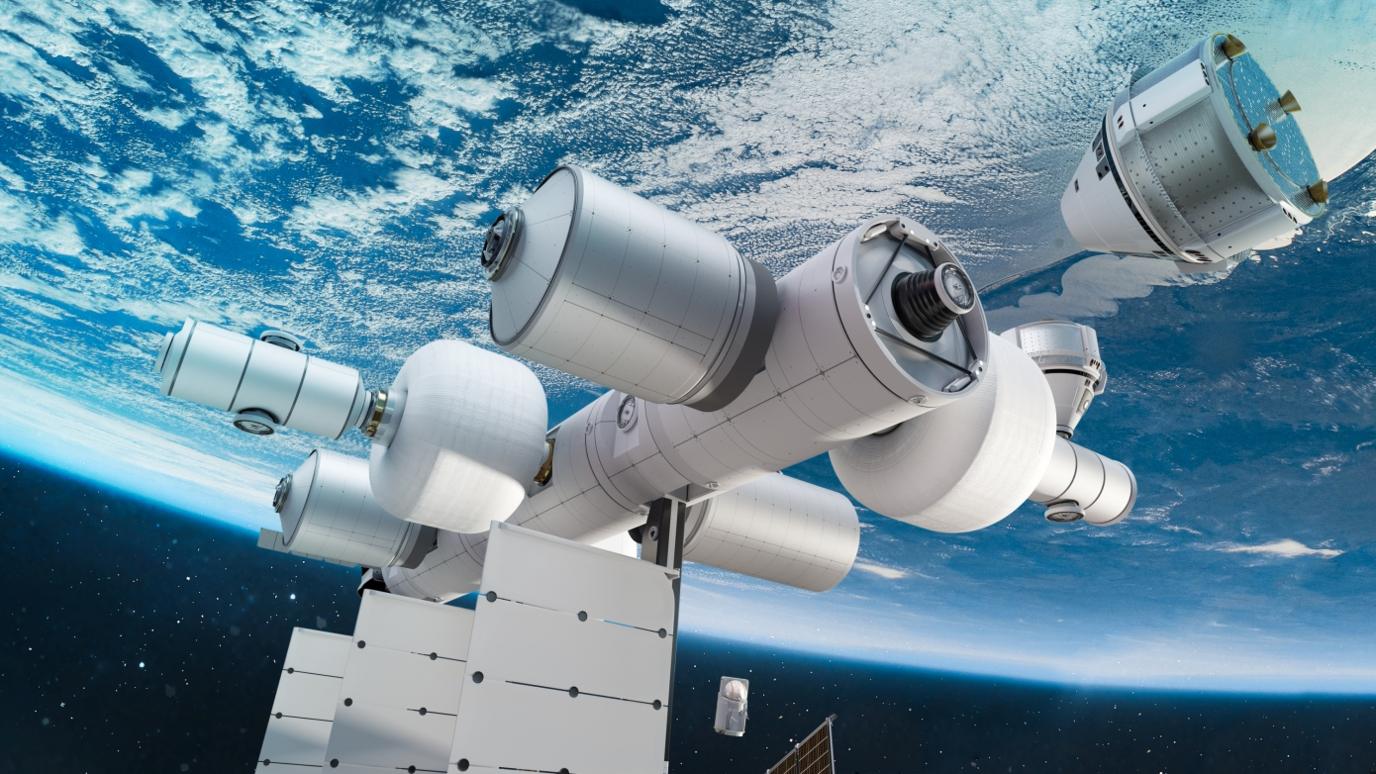

Astronauts on the ISS are increasingly having to take precautionary measures when fragments from old satellites and rockets come close

The US has condemned Russia for conducting a "dangerous and irresponsible" missile test that it says endangered the crew aboard the International Space Station (ISS).

The test blew up one of Russia's own satellites, creating debris that forced the ISS crew to shelter in capsules.

The station currently has seven crew members on board - four Americans, a German and two Russians.

The space station orbits at an altitude of about 420km (260 miles).

"Earlier today, the Russian Federation recklessly conducted a destructive satellite test of a direct ascent anti-satellite missile against one of its own satellites," US state department spokesman Ned Price said at a briefing.

"The test has so far generated over 1,500 pieces of trackable orbital debris and hundreds of thousands of pieces of smaller orbital debris that now threaten the interests of all nations."

Nasa administrator Bill Nelson said he was outraged at the incident.

"With its long and storied history in human spaceflight, it is unthinkable that Russia would endanger not only the American and international partner astronauts on the ISS, but also their own cosmonauts" as well as Chinese "taikonauts" aboard China's space station, he said in a statement.

Russian space agency Roscosmos downplayed the incident.

"The orbit of the object, which forced the crew today to move into spacecraft according to standard procedures, has moved away from the ISS orbit. The station is in the green zone," the agency tweeted, external.

Space debris is becoming a major problem

The wayward material passed by without incident, but its origin is now under the spotlight.

It appears to have come from a broken-up Russian satellite, Kosmos-1408. A spy satellite launched in 1982, it weighed over a tonne and had ceased working many years ago.

LeoLabs, a space debris-tracking company, said its radar facility in New Zealand had picked up multiple objects where the long-defunct spacecraft should have been.

Mr Price described the Russian action as "dangerous and irresponsible" and said it demonstrated the country's "claims of opposing weaponisation of space are disingenuous and hypocritical.

"The US will work with our partners and allies to respond to their irresponsible act," he said.

And UK Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said the test "shows a complete disregard for the security, safety and sustainability of space".

"The debris resulting from this test will remain in orbit putting satellites and human spaceflight at risk for years to come," he added.

It's difficult not to view anti-satellite missile tests as a form of madness.

It's impossible to control the debris field that results from a high-velocity impact. Thousands of fragments are produced. Some will be propelled downwards towards Earth and out of harm's way, but many will also head to higher altitudes where they will harass operational missions for years into the future - including those of the nation state that carried out the test.

What must the Russian cosmonauts on the space station have been thinking when they took shelter in their Soyuz capsule early on Monday because of the risk debris from this test might intersect with their orbital home?

Space junk is a rapidly worsening situation. Sixty-four years of activity above our heads means there are now roughly a million objects running around up there uncontrolled in the size range of 1cm (0.4in) to 10cm.

An impact from any one of these could be mission-ending for a vital weather or telecommunications satellite. Nations need to be clearing up the space environment, not polluting it still further.

A number of countries have the ability to take out satellites from the ground, including the US, Russia, China and India.

Testing of such missiles is rare, but always draws widespread condemnation whenever it occurs, because it pollutes the space environment for everyone.

When China destroyed one of its retired weather satellites in 2007, it created more than 2,000 pieces of trackable debris. This material posed an ongoing hazard to operational space missions, not least those of China itself.

Brian Weeden, an expert in space situational awareness, earlier said that if it was confirmed Russia had conducted a test that endangered the ISS, the conduct would have been "beyond irresponsible".

Watch: Astronauts return to Earth on SpaceX capsule (10 November 2021 report)

The space station occupies an orbital shell that other operators try to keep clear of hardware, either working or retired.

However, the astronauts are increasingly having to take precautionary measures when fragments from old satellites and rockets come uncomfortably close.

The velocities at which this material moves means it could easily puncture the walls of the station's modules.

Precautionary measures usually involve closing hatches between the modules, and, as happened on Monday, climbing into the capsules that took the astronauts up to the station. These vehicles stay attached to the ISS throughout the crews' tours of duty in case there is a need for a rapid "lifeboat" escape.

- Published26 October 2021

- Published17 October 2021

- Published19 September 2021

- Published9 September 2021