Scientists claim big advance in using DNA to store data

- Published

If stored as DNA, every film ever made could be stored in a space smaller than a sugar cube

Scientists say they have made a major step forward in efforts to store information as molecules of DNA, which are more compact and long-lasting than other options.

The magnetic hard drives we currently use to store computer data can take up lots of space.

And they have to be replaced over time.

Using life's preferred storage medium to back up our precious data would allow vast amounts of information to be archived in tiny molecules.

The data would also last thousands of years, according to scientists.

A team in Atlanta, US, has now developed a chip that they say could improve on existing forms of DNA storage by a factor of 100.

"The density of features on our new chip is [approximately] 100x higher than current commercial devices," Nicholas Guise, senior research scientist at Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), told BBC News.

"So once we add all the control electronics - which is what we're doing over the next year of the program - we expect something like a 100x improvement over existing technology for DNA data storage."

The technology works by growing unique strands of DNA one building block at a time. These building blocks are known as bases - four distinct chemical units that make up the DNA molecule. They are: adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine.

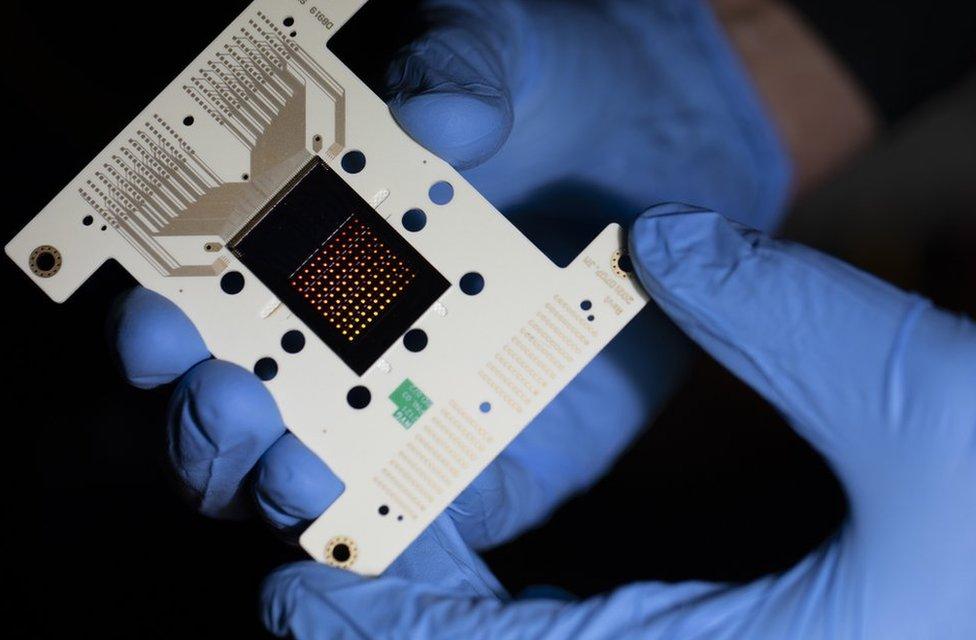

The microchip will be used for growing multiple strands of DNA in parallel

The bases can then be used to encode information, in a way that's analogous to the strings of ones and zeroes (binary code) that carry data in traditional computing.

There are different potential ways to store this information in DNA - for example, a zero in binary code could be represented by the bases adenine or cytosine and a one might be represented by guanine or thymine. Alternatively, a one and zero could be mapped to just two of the four bases.

Scientists have said that, if formatted in DNA, every movie ever made could fit inside a volume smaller than a sugar cube.

Given how compact and reliable it is, it's not surprising there is now broad interest in DNA as the next medium for archiving data that needs to be kept indefinitely.

The structures on the chip used to grow the DNA are called microwells and are a few hundred nanometres deep - less than the thickness of a sheet of paper.

The current prototype microchip is about 2.5cm (one-inch) square and includes multiple microwells, allowing several DNA strands to be synthesised in parallel. This will allow larger amounts of DNA to be grown in a shorter space of time.

How DNA can be used to store computer data

Because it's a prototype, not all the microwells are wired up yet. This means the total amount of DNA data that can be written with this particular chip is currently less than what leading synthesis companies can produce on commercial chips.

However, Dr Guise explained, when everything's up and running, that will change. The current record for DNA digital data storage is around 200MB, with single synthesis runs lasting about 24 hours. But the new technology could write 100 times more DNA data in the same amount of time.

The high cost of DNA storage has so far restricted the technology to "boutique customers", such as those seeking to archive information in time capsules.

The team at GTRI believes their work could help reshape the cost curve. It has partnered with two California biotech companies to make a commercially-viable demonstration of the technology: Twist Bioscience and Roswell Biotechnologies.

GTRI's Nicholas Guise tests electronics on the microchip

DNA data storage won't initially replace server farms for information that must be accessed quickly and often. Because of the time required for reading the sequence, the technique would be most useful for information that must be kept available for a long time, but accessed infrequently.

This type of data is currently stored on magnetic tapes which should be replaced around every 10 years.

With DNA, however, "as long as you keep the temperature low enough, the data will survive for thousands of years, so the cost of ownership drops to almost zero", Dr Guise explained.

"It only costs much money to write the DNA once at the beginning and then to read the DNA at the end. If we can get the cost of this technology competitive with the cost of writing data magnetically, the cost of storing and maintaining information in DNA over many years should be lower."

DNA storage has a higher error rate than conventional hard drive storage. In collaboration with the University of Washington, GTRI researchers have come up with a way of identifying and correcting those errors.

The work has been backed by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA), which supports science geared towards overcoming challenges relevant to the US intelligence community.

Follow Paul on Twitter., external