The world's first octopus farm - should it go ahead?

- Published

News that the world's first commercial octopus farm is closer to becoming reality has been met with dismay by scientists and conservationists. They argue such intelligent "sentient" creatures - considered able to feel pain and emotions - should never be commercially reared for food.

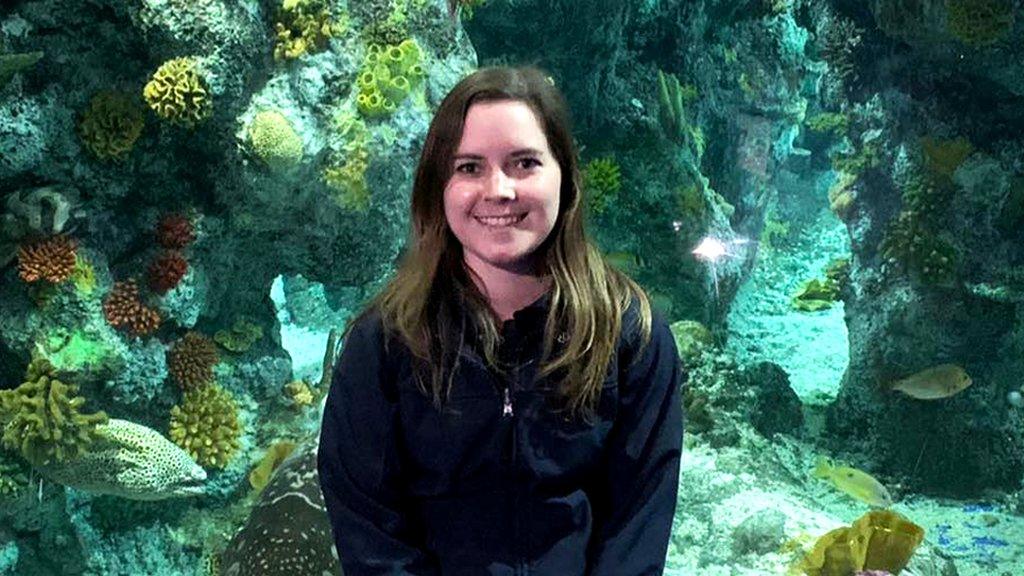

Playing with a Giant Pacific Octopus is part of Stacey Tonkin's job. When she lifts the lid on the tank to feed the creature known as DJ - short for Davy Jones - he often scoots out from his cave to see her and stick his arms on the glass. That's if he's in a good mood. Octopuses live to be about four - so, at one year old, she says that he's the equivalent of a teenager.

"He definitely exhibits what you'd expect a teenager to be like - some days he's really grumpy and sleeps all day. Then other days he's really playful and active and wants to charge around his tank and show off."

DJ at Bristol Aquarium

Stacey is one of a team of five aquarists at Bristol Aquarium, and she sees DJ reacting differently to each of them. She says he will happily stay still, and hold her hand with his tentacles.

The keepers feed the octopus with mussels and prawns and bits of fish and crab. Sometimes they put the food in a dog toy for him to tease out with his tentacles, so he can practise his hunting skills.

She says his colour changes with his moods. "When he's an orangey brown, it's more like an active or playful kind of feeling. Speckly is more curious and interested. So he'll be swimming around orange and brown, then he'll come over and sit beside you and go all speckly and just look at you, which is quite amazing.

Stacey says the octopus shows his intelligence through his eyes. "When you look at him, and he looks at you, you can sense there's something there."

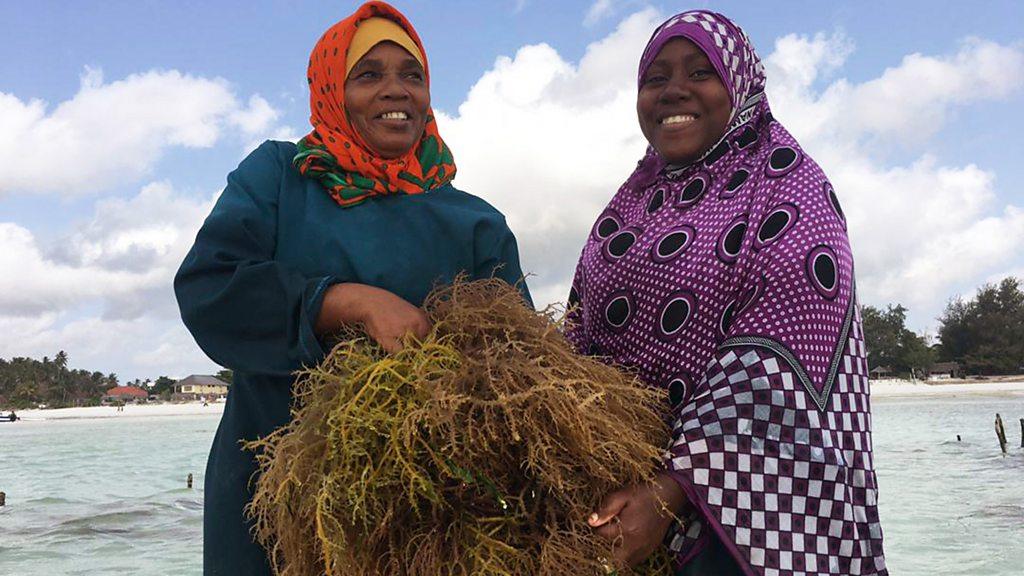

Stacey Tonkin, Bristol Aquarium

The level of awareness that Stacey witnesses first-hand is to be recognised in UK law through an amendment to the Animal Welfare (Sentience) Bill, external.

The change has come after a team of experts sifted through more than 300 scientific studies, external and concluded that octopuses were "sentient beings" and there was "strong scientific evidence" that they could experience pleasure, excitement and joy - but also pain, distress and harm.

The authors said they were "convinced that high-welfare octopus farming was impossible" and the government "could consider a ban on imported farmed octopus" in future.

But octopus tentacles sizzle in pans, coil on plates and float in soups around the world - from Asia to the Mediterranean, and increasingly the USA. In South Korea, the creatures are sometimes eaten alive. The number of octopuses in the wild are decreasing and prices are going up. An estimated 350,000 tonnes are caught each year - more than 10 times the number caught in 1950.

Against that background, the race to discover the secret to breeding the octopus in captivity has been going on for decades. It's difficult - the larvae only eat live food and need a carefully controlled environment.

The Spanish multinational, Nueva Pescanova (NP) appears to have beaten companies in Mexico, Japan and Australia, to win the race, external. It has announced that it will start marketing farmed octopus next summer, to sell it in 2023.

The company built on research done by the Spanish Oceanographic Institute (Instituto Español de Oceanografía), looking at the breeding habits of the Common Octopus - Octopus vulgaris. NP's commercial farm will be based inland, close to the port of Las Palmas in the Canary Islands according to PortSEurope, external.

It's reported the farm will produce 3,000 tonnes of octopus per year. The company has been quoted as saying it will help to stop so many octopus being taken from the wild.

Octopuses drying on a line

Nueva Pescanova has refused to reveal any details of what conditions the octopuses will be kept in, despite numerous approaches by the BBC. The size of the tanks, the food they will eat and how they will be killed are all secret.

The plans have been denounced by an international group of researchers as "ethically and ecologically unjustified", external. The campaign group Compassion in World Farming (CIWF) has written to the governments of several countries, external - including Spain - urging them to ban it.

Dr Elena Lara, CIWF's research manager, is angry. "These animals are amazing animals. They are solitary, and very smart. So to put them in barren tanks with no cognitive stimulation, it's wrong for them."

She says anyone who has watched the 2021 Oscar-winning documentary - My Octopus Teacher - will appreciate that.

An octopus hiding in a shell

Octopuses have large, complex brains. Their intelligence has been proven in numerous scientific experiments. They've been observed, external using coconut and sea shells to hide and defend themselves and have shown they can learn set tasks quickly. They've also managed to escape from aquariums and steal from traps set by people fishing.

What's more, they have no skeletons to protect them and are highly territorial. So they could be easily damaged in captivity and - if there was more than one octopus in a tank - experts say they could start to eat each other.

If the octopus farm does open in Spain, it seems the creatures bred there would receive little protection under European law. Octopuses - and other invertebrate cephalopods - are considered as sentient beings, but EU law covering farm animal welfare is only applied to vertebrates - creatures that have backbones. Also, according to CIWF, there is currently no scientifically validated method for their humane slaughter.

Farming in the sea

Aquaculture is the term given to the rearing of aquatic animals for food

It is the fastest-growing food-producing sector, external in the world

The global aquaculture market is growing at around 5% a year and is projected to be worth almost $245bn (£184bn) by 2027

Some 580 aquatic species are farmed around the world

As the human population grows, global aquaculture could provide a vital source of food

Fish kept in captivity tend to be more aggressive and contract more diseases, external

The EU recently published guidelines, external acknowledging the "lack of good husbandry practises" and "research gaps" in aquaculture's impact on animal and public health

Humans and octopuses had a common ancestor 560 million years ago, and evolutionary biologist Dr Jakob Vinther, from the University of Bristol, also has concerns.

"We have an example of an organism that has evolved to have an intelligence that is extremely comparable to ours." Their problem-solving abilities, playfulness and curiosity are very similar to those of humans, says Dr Vinther - and yet they're otherworldly.

"This is potentially how it would look if we were ever going to meet an intelligent alien from a different planet."

Nueva Pescanova says on its website that it is "firmly committed to aquaculture [farming seafood] as a method to reduce pressure on fishing grounds and ensure sustainable, safe, healthy, and controlled resources, complementing fishing".

But CIWF's Dr Lara argues that NP's actions are purely commercial and the company's environmental argument is illogical. "It doesn't mean that fishermen will stop fishing [octopuses]."

She argues that farming octopuses could add to the growing pressure on wild fish stocks. Octopuses are carnivores and need to eat two-to-three times their own weight in food to live. Currently around one-third of the fish caught around the planet is turned into feed for other animals - and roughly half of that amount goes into aquaculture. So farmed octopus could be fed on fish products from stocks already overfished.

Dr Lara is concerned consumers who want to do the right thing may think eating farmed octopus is better than octopus caught in the wild. "It's not more ethical at all - the animal is going to be suffering its entire life," she says. And a 2019 report, external - led by associate professor of environmental studies at NYU, Jennifer Jacquet - argues that banning octopus farming wouldn't leave humans without enough to eat. It will mean "only that affluent consumers will pay more for increasingly scarce, wild octopus," it states.

Pulpo a la Gallega is a common Spanish dish

The whole debate is fraught with cultural complexities.

Factory farming on land has evolved differently around the world. Pigs, for example, have been shown to be intelligent, external - so what's the difference between a factory-farmed pig producing a bacon sandwich, and a factory-farmed octopus being put in the common Spanish dish Pulpo a la Gallega?

The conservationists argue the sentience of many farmed animals wasn't known when the intensive systems were set up, and the mistakes of the past shouldn't be repeated.

Because pigs have been domesticated for many years, we have enough knowledge about their needs and know how to improve their lives, says Dr Lara. "The problem with octopus is that they are completely wild, so we don't know exactly what they need, or how we can provide a better life for them."

Given all we know about the intelligence of octopuses, and the fact they are not essential for food security, should an intelligent, complex creature start to be mass-produced for food?

"They are extremely complex beings," says Dr Vinther. "I think as humans we need to respect that if we want to farm them or eat them."

Follow Claire on Twitter @BBCMarshall, external

Related topics

- Published23 July 2021

- Published4 November 2021

- Published4 November 2021

- Published19 September 2021