Interstellar probe: A mission for the generations

- Published

The aim would be for the interstellar probe still to be working 100 years after launch

Imagine working on a project you know you have no hope of seeing through to completion. Would you have the motivation to even get it going?

Absolutely, says Ralph McNutt from Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU-APL) in the US.

McNutt, with colleagues, has just published a detailed report, external that envisions a long-lived interstellar probe - a mission to the space between the stars.

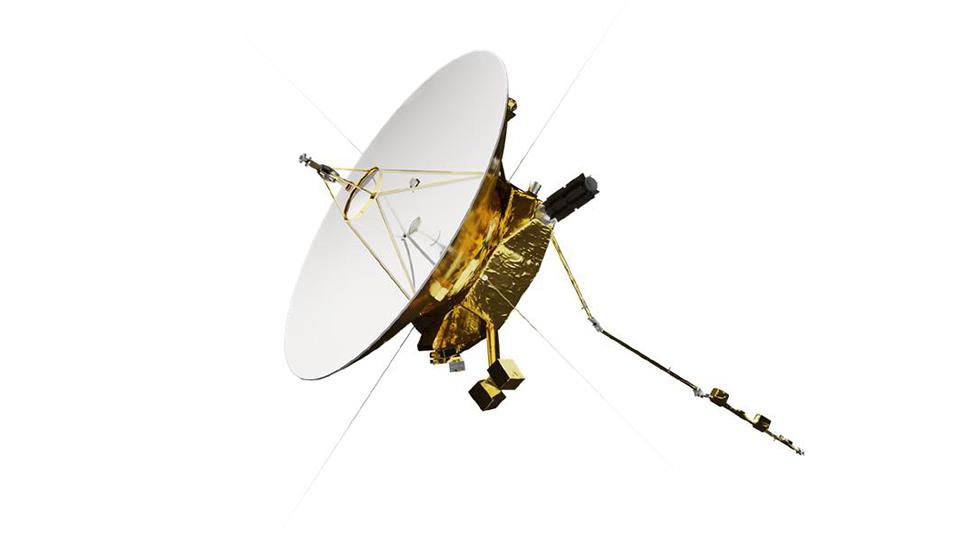

Nasa's legendary Voyagers, external are travelling through this domain right now, but McNutt's probe would go further and faster and would expect still to be working 50-100 years after leaving Earth.

"Suppose this thing launched in 2036, and it got to the end of the nominal mission in 2086," he pondered. "That puts me at about 130 years old. I'm not going to worry about it. You have to hand these things off. I say to people, 'if you're into instant gratification, do not get involved with space exploration'."

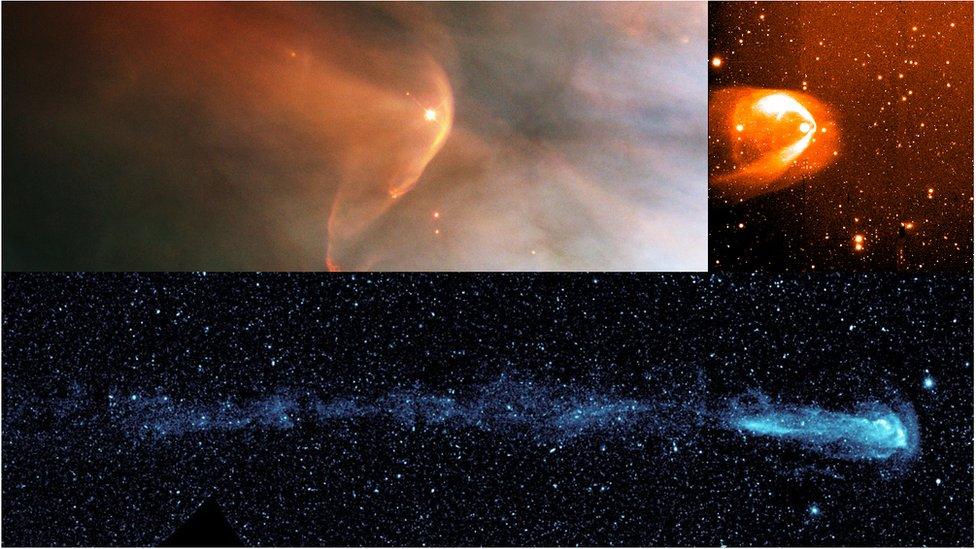

Telescope views of the heliospheric bubbles around other stars

Voyagers 1 and 2 made history in the 2010s when they left the bubble of hot gas that surrounds our Sun, its so-called heliosphere, and entered the interstellar medium - the region of space dominated by the particles, dust and magnetic fields generated by other stars.

Today, more than 40 years after setting out on their grand adventure, these sentinels have traversed, in the case of Voyager 1, some 23 billion km; or 155 times the Sun-Earth distance, a separation scientists refer to as the Astronomical Unit to keep the numbers manageable.

The Voyagers have told us new things about the galactic environment in which our Sun lives, but that wasn't their primary goal. They were originally conceived to survey the outer planets - Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus - which they completed in spectacular fashion. Their late career move was just a bonus.

McNutt's team wants to reverse the priorities.

The Voyagers: Scientists 'amazed' 1970s space probes still work

"The Voyagers had instruments on board that were tailored to the exploration of planets. They did not have the dedicated instrumentation to really understand processes at the edge of the heliosphere," said JHU-APL's Elena Provornikova. The proposed interstellar probe would be built from the bottom up to deliver the desired science, she added.

To be clear, this is not a mission to another star. The nearest star systems are too far away for an operational probe to reach with current technology. But the spacecraft would be an enduring traveller in the gap between the stars.

The new study, initiated at the behest of Nasa's heliophysics division, is described as a deep dive on the engineering required and runs to almost 500 pages.

The working concept is an 850kg spacecraft, equipped with sensors to measure parameters such as charged and neutral particles, magnetic fields and dust.

The probe would be launched around 2036 on a super-heavy-lift rocket with additional stages to give it a thumping escape velocity.

The spacecraft would take a mere 6.5 hours to pass the orbit of the Moon and reach Jupiter in seven months for a sling-shot manoeuvre that pumped it up to a peak speed of six-to-seven astronomical units per year. That's over a billion km every 12 months.

To be funded, the probe concept will need wide support in the space and solar physics community

But it's also longevity that matters. The Voyagers are now prioritising instruments because their radioisotope thermoelectric generators have become so weak. But with two next-generation nuclear batteries now under development with Nasa, it's expected the interstellar probe could still be sending data back to Earth a century into an extended mission when it would be hundreds of AU away.

"What our study has done is take these dreams that the scientists have and put the engineering behind them," explained payload systems lead for the study team, Alice Cocoros.

"And we've come to the conclusion that with near-term technologies, technologies that won't need a whole lot of infusement or development, we can accomplish all the science we want to do with this mission concept, which is pretty exciting."

And when it came to it, if the funding agencies were so minded the probe could still include a flyby of an interesting object on its way out of the Solar System. Perhaps another pass of Pluto which we saw for the first time with the New Horizons mission in 2015, or maybe a rendezvous with one of those icy cousins that share the same far-flung orbit around the Sun.

But there's more than enough investigation to be done beyond the heliosphere. The Voyagers' data has piqued many new questions about the nature of our Sun's bubble, says project scientist Pontus Brandt.

"Four-point-six billion years ago, our Solar System started to take form, and with it this magnetic bubble which shields us from all the dust and plasma that we plough through on our journey through the galaxy.

"Having this interstellar probe will allow us to not only understand the current state but also understand where we come from, and how this has affected evolution; and where we're going next. Not many people know but we are about to exit our local interstellar cloud that this heliosphere has been ploughing through for the last 60,000 years. We're entering a completely new region."

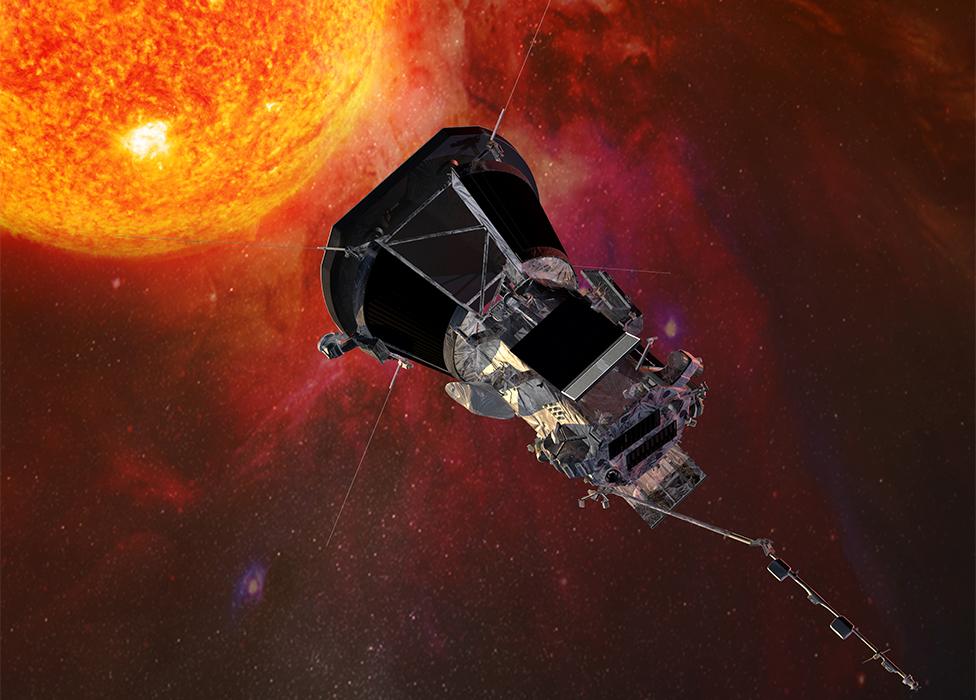

Artwork: Parker Solar Probe is currently investigating the region where the bubble is generated

Whether the interstellar probe gets the funding it needs to get off the ground (about $1.6bn; £1.2bn) will depend on the wider support of the solar and space physics community in the US and what they consider to be the most pressing research topics in their field.

They may think the money would be better spent on projects investigating the Sun's influence closer to home. Right now, with the Parker Solar Probe, they're enjoying the delights of flying through the Sun's outer atmosphere, a mere 8 million km from the star's surface, or photosphere - the very place from where everything that fills the heliosphere originates.

And it should be said, there are other concepts out there. China has a proposition it's working on called Interstellar Express. And the Russian-Israeli entrepreneur Yuri Milner has proposed Breakthrough Starshot, a private venture to send a fleet of tiny "StarChips" in the direction of the nearest star system.

"There are two things that really inspire people," said Pontus Brandt.

"One is obviously 'to boldly go where no-one has gone before', but the other aspect is the beauty of a long mission, where you do it for your future generations because inevitably that is where space exploration is going to take us. We do this for the future generations."

The JHU-APL team discussed its report at the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting in New Orleans.