James Webb Space Telescope: Everything is 'hunky dory'

- Published

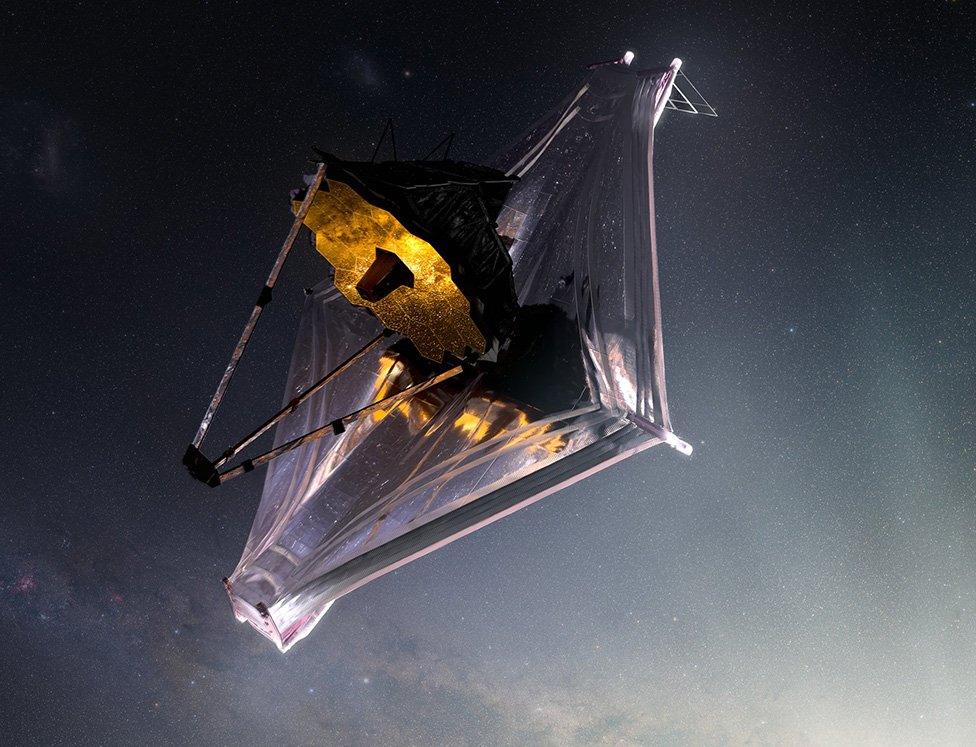

Artwork: The fully deployed Webb telescope will have a kite-like shield the size of a tennis court

So far, so good. The US space agency says the post-launch set-up of the new James Webb telescope has gone very well.

"As smoothly as we could have hoped for."

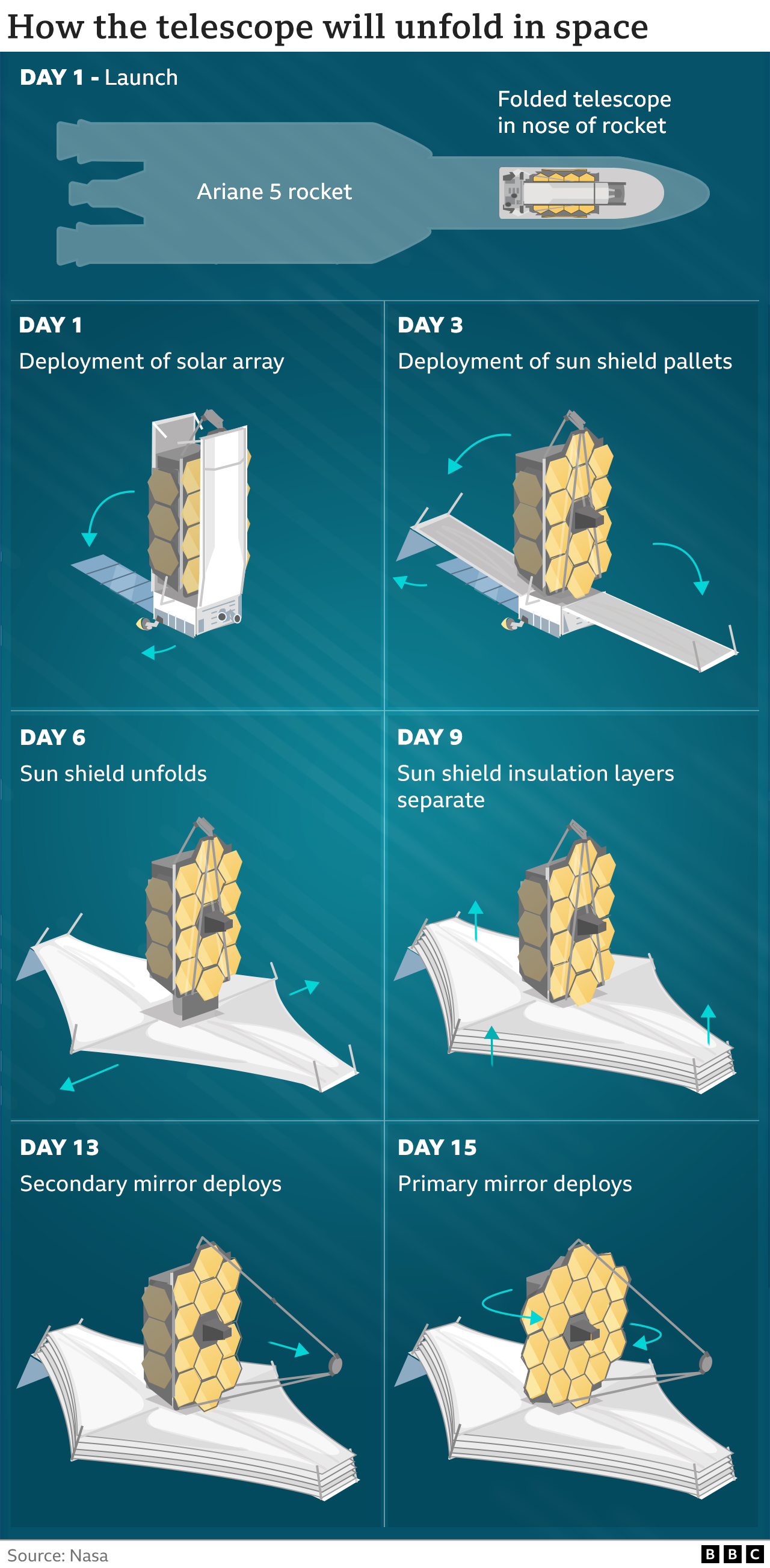

Engineering teams are in the middle of unpacking the observatory from its folded launch configuration to the layout needed for operations.

This involves the deployment of several structures, the most critical of which are Webb's mirrors and sun shield.

Monday saw the start of what is probably the most complex set of activities - the separation and tensioning of the five individual layers that make up the shield.

Watch the moment Webb moves away from its launch rocket to begin its mission

Each membrane in the shield is as thin as a human hair and must be gently pulled tight to form a rigid, kite-like barrier the size of a tennis court.

The task was practised multiple times on the ground with full-scale and sub-scale models, which Nasa's Bill Ochs says gives him confidence that all will go well.

"I don't expect any drama," the project manager told reporters on Monday. "The best thing for operations is 'boring'. And that's what we anticipate over the next three days - to be boring."

Engineers refer to "single point failures" to describe the actions, which, if they don't occur on cue and in the right order, are likely to scupper the whole undertaking. Webb must get past 344 of these hurdles to achieve its operational layout.

If the sun shield opens perfectly - which may even be accomplished as early as Tuesday - then 75% of those failure modes will have been overcome.

Mission controllers at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, would then move on to deploying Webb's mirrors

The telescope has a secondary reflector that must be extended on long booms in front of the primary mirror. Friday is the current target for this.

The main mirror has "wings" that were tucked back for launch but which must now be rotated through 90 degrees to make a full, 6.5m-wide surface. Again, assuming things continue to run like clockwork, this should happen over the weekend.

The unfolding schedule has slipped somewhat from the prelaunch plan, but not because of any particular problems, said Bill Ochs. The engineering teams were simply taking a steady, methodical approach to their work, he stressed.

"We are still in the 'getting to know you' phase with the telescope. All satellites will be a little bit different on orbit than they are on the ground," he explained.

"It takes time to get to understand their characteristics, and that's a lot of what we've been doing over the last week, as well as still making excellent progress on the commissioning timeline."

Practice makes perfect: Engineers have rehearsed the sun shield deployment over and over again

One of these learning moments involved the teams getting a better handle on how to manage the temperatures inside the motors that are used to drive the sun shield's deployment. A second involved the fine-tuning of Webb's solar array so that it can output the necessary power for the separation and tensioning of the membranes - as well as the mirror unpacking.

"Everything is hunky dory and doing well," said Amy Lo from Northrop Grumman, the American aerospace company that assembled Webb.

"The rebalancing of the array gives us quite a lot of margin for the expected increase in power that we will be needing as we proceed on commissioning."

James Webb was launched on 25 December on an Ariane rocket from French Guiana.

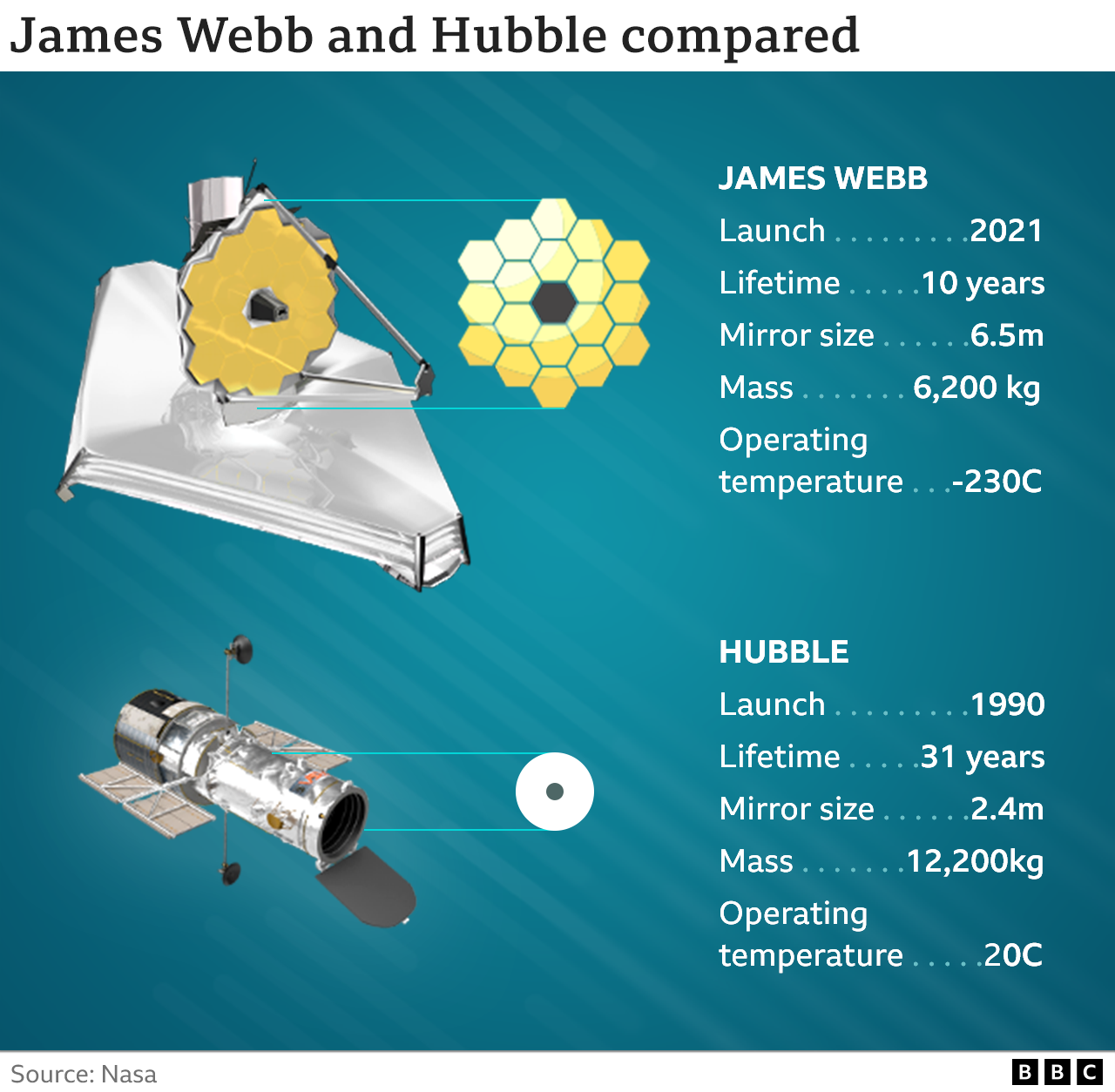

The telescope is regarded as the successor to the Hubble space observatory which is now 31 years old and nearing the end of its operational life.

Webb will do similar science to Hubble but with the next-generation technologies that allow it to see deeper into cosmos and, therefore, further back in time. Indeed, scientists expect the new facility to detect the very first stars to ignite after the Big Bang more than 13.5 billion years ago.

But, unlike Hubble, Webb cannot be serviced by astronauts and so cannot achieve the same longevity as its predecessor.

That said, officials now think Webb will work for "a lot more" than the 10 years originally envisaged because its Ariane rocket was so accurate.

The European booster put Webb on a near-perfect trajectory with just the right amount of velocity. This performance meant the telescope didn't have to use so much of its own fuel when making later course refinements. The saved fuel will now be available for the everyday manoeuvres required to keep Webb sitting tidily at its observing position 1.5 million km from Earth.

James Webb is a joint venture between the American, European and Canadian space agencies.