How a colossal block of ice became an obsession

- Published

Did you develop an obsession during lockdown? Did those long weeks and months take you down surprising avenues? Where did your mind wander?

The Swiss-based British artist Kevin Eason, external found himself thinking about Antarctica and one particularly large chunk of ice. He'd read an article, by me as it happens, about a 300-billion-tonne iceberg that had recently calved from the east of the continent. D28, it's called; although that's not its only name as I'll explain.

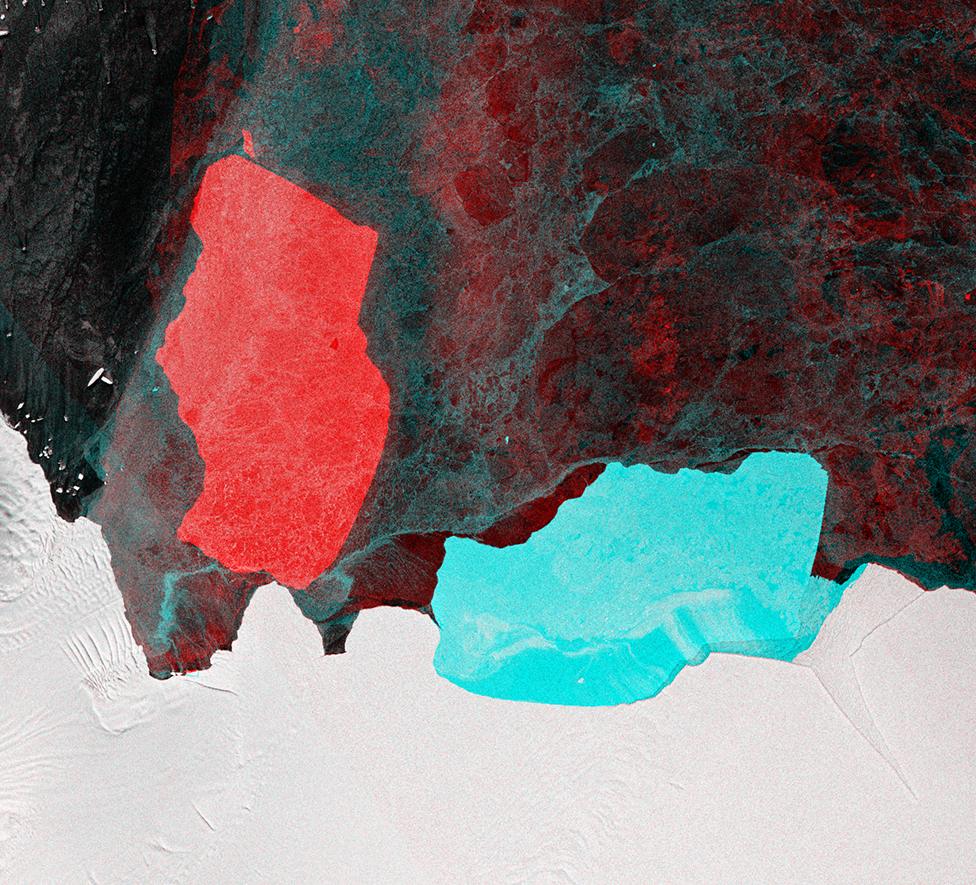

Kevin's interest was piqued by the satellite images that scientists began publishing of this berg, along with the sometimes surprising colours they would choose to render scenes and emphasise contrast.

"It started out quite small. Just little studies," the artist recalls.

"I found myself taking images that I'd see of D28, dropping them into Photoshop, and making colour samples. I was basically making pantones from Antarctica based on images that were being circulated around the internet.

"I spent weeks mixing the paint to match these colours. I guess it was a form of meditation. And then I was bound to the studio, and so it just started developing into something."

The series marks the years 2019, 2021, 2023, and 2025

That something is a series of four oil paintings depicting the life of D28. The first picture captures the definitive and distinctive outline of the berg in the days immediately after it broke from the edge of Antarctica's Amery Ice Shelf. The ones that follow are from Kevin's imagination.

The series marks the years 2019, 2021, 2023, and 2025. We don't know when that final, speculative view will occur, but it will happen eventually. Icebergs are born to wither and melt away.

Those people who've seen the series have had various reactions, but some of the themes are common. You won't be surprised to learn that when asked to describe an emotion or feeling, the words that viewers used included "transformation", "scale", "time", "isolation", "drifting", "silence", "change", "awareness", and "loss".

Scientists will often colour satellite imagery to emphasise features

And, quite naturally, Kevin's D28 journey has brought environmental issues - and the loss of ice - to the forefront of his mind. Being in Switzerland, this is a very topical concern. Alpine glaciers are retreating rapidly in our warming climate, prompting local people to blanket the ice streams in Summer to try to protect them.

"If I can produce a work of art that might have some sort of impact, or assist in some way; that might help slow down consumption or make people consider things a little bit more by taking fewer flights, or driving their cars less - that's got to be a good way to go," says Kevin.

D28 2023: Icebergs are born to wither and melt away

My own interest in D28 goes back to the mid-2000s, long before it calved. At that time I was reporting research on the Amery Ice Shelf, external that sought to predict which part of this vast, floating wedge of ice might break first, and when.

Attention had focused on an area that became nicknamed "Loose Tooth", external because it looked in satellite images like a child's wobbly front tooth.

The team studying the cracks developing in the ice shelf thought a calving might be imminent. It wasn't. Loose Tooth is still there, still wobbling, still hanging on to the Amery. It was the adjacent, 1,636-sq-km section that came away - the big berg now formally designated D28 (the largest Antarctic bergs are given an official listing by the US National Ice Center, external).

D28/Molar Berg viewed in the foreground at an oblique angle from the International Space Station

I joked with the Amery research team, led by Prof Helen Fricker from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, that perhaps another dental analogy was needed. "It is the molar compared to a baby tooth," Helen laughed. And the nickname stuck.

People regularly now post satellite pictures of "Molar Berg", aka D28, as it bumps and grinds its way around the Antarctic coast. Even astronauts on the space station can see it, albeit from an oblique angle.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

A keen observer is Dr Catherine Walker from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. As a graduate student in the 2000s, she was tasked with studying those cracks in the Amery Ice Shelf.

"It was actually sort of sad to see it go, because it was something that I'd had all this time, and then it was gone," Catherine tells me.

"I really appreciate Kevin's paintings. I feel like that's my entire career right there."

There's a growing appreciation of these city-sized bergs (Molar Berg was bigger than Greater London when it broke away).

They dump huge quantities of fresh water into the wider ocean, along with iron and other minerals scraped off the Antarctic landmass. This influences the behaviour of local currents and food webs.

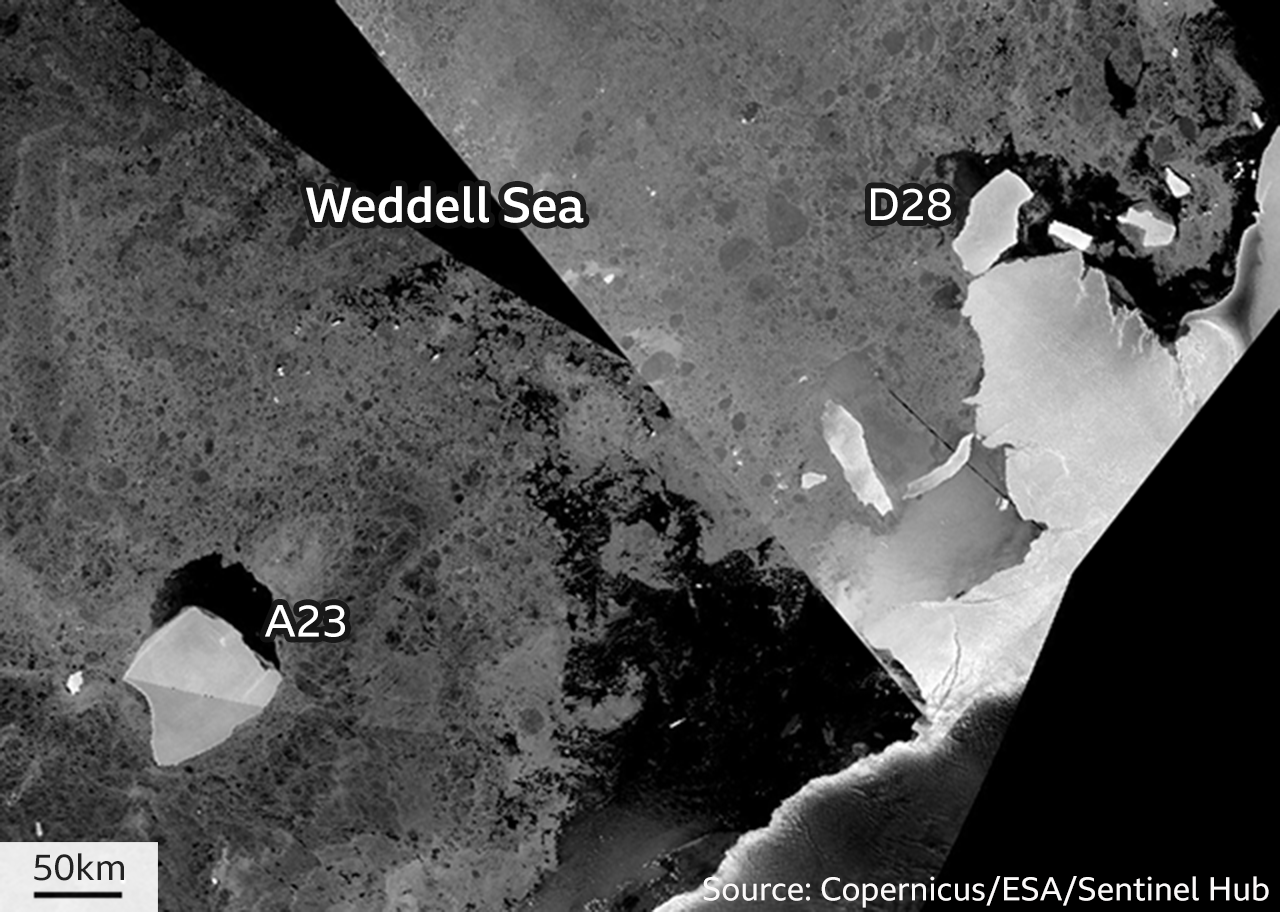

D28/Molar Berg's travels have taken it a full quarter turn around the White Continent. It's now entered the Weddell Sea which is directly south of the Atlantic Ocean.

Each summer, the Rhône Glacier is dressed in white tarpaulins to slow its melting

And it just so happens that it's moving in the direction of what is currently the world's biggest iceberg - a near-4,000-sq-km monster known as A23, which has been pinned fast to the Weddell seafloor for three decades.

"Yep, that's one of mine, too," says Catherine. "I always watch A23 because we're the same age. It calved in 1986 and it's started to wiggle recently.

"What's the fascination with these giant icebergs? I guess it has something to do with their size; they're so much bigger than you can imagine - like Everest or K2. You look at them and wonder: how do they hold themselves together."

I think that's right. Their great scale is truly awesome. But for me it's also the way such imposing objects, built from snows that originally fell on Antarctica thousands of years ago, and which seem as though they ought to be so permanent, can suddenly disintegrate and fade away in a very short time.

D28/Molar Berg is moving towards A23, which is so big it's become pinned to the seafloor

You can follow Jonathan on Twitter: @BBCAmos, external