'Alien-like' life thrives on dead matter in Arctic deep

- Published

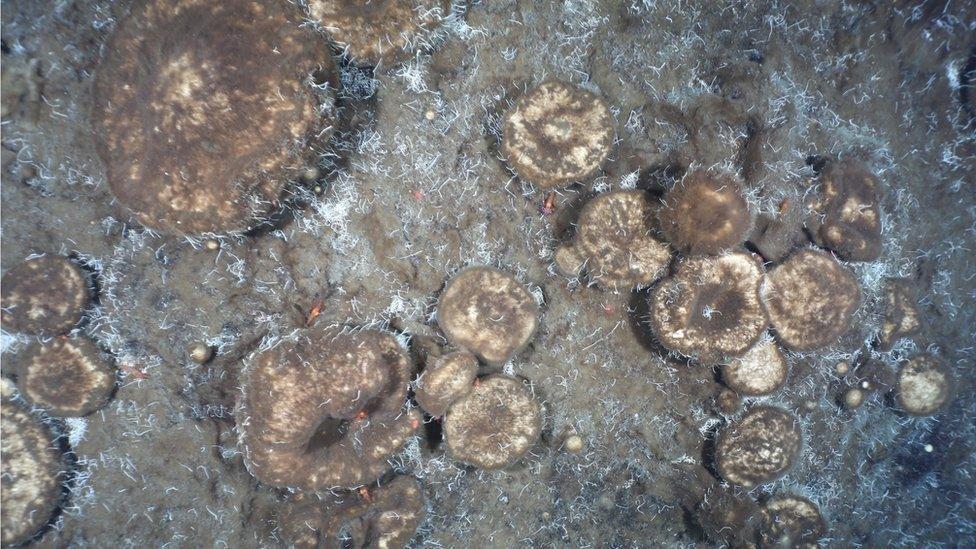

The sponges live on top of extinct volcanoes on the sea floor

Scientists say they've solved the mystery of how giant sponges flourish in the deep, icy waters of the Arctic.

The sea sponges survive by feeding on the remains of worms and other extinct animals that perished thousands of years ago, they suggest.

Sponges are very simple ancient animals found in seas across the world, from deep oceans to shallow tropical reefs.

They have been found living in large numbers and to impressive size at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean.

These massive "sponge gardens" are part of a unique ecosystem thriving beneath the ice-covered ocean near the North Pole, said Dr Teresa Morganti from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany.

"We have found massive sponges - they can reach up to one metre in diameter," she said.

"This is the first evidence of sponges eating ancient fossil matter."

The Arctic is one of the most affected regions by climate change

By dangling a camera deep beneath the ice, researchers were able to photograph the collections of sponges that form a garden on the sea floor.

At the time, they were mystified over how the primitive animals survived in the cold, dark depths far from any known food source.

More recently, after analysing samples from the Arctic expedition, they found the sponges were on average 300 years old.

And they survive by snacking on the leftovers of an extinct community of animals - with the help of friendly bacteria that produce antibiotics.

"Where the sponges like to live, there is a layer of dead material, said Prof Antje Boetius of the Alfred Wegener institute in Bremerhaven, who led the expedition to the Arctic.

"And finally it occurred to us that this might be the solution to why the sponges are so abundant, because they can tap into this organic matter with the help of the symbionts."

The sponges act as ecosystem engineers, maintaining the health of the environment

The discovery shows we have much more to learn about Planet Earth and there may be more life forms waiting to be discovered beneath the ice, she added.

"There is so much alien-like life and especially in the ice-covered seas where we barely have the technology to access, to look around and to make a map," she said.

But with Arctic sea ice retreating at an unprecedented rate, the researchers warn that this unique web of life is coming under increasing pressure from climate change.

According to scientific measurements, both the thickness and extent of summer sea ice in the Arctic have shown a dramatic decline in the past 30 years, which is consistent with observations of a warming Arctic.

"With sea ice cover rapidly declining and the ocean environment changing, a better knowledge of hotspot ecosystems is essential for protecting and managing the unique diversity of these Arctic seas under pressure," said Prof Boetius.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external.