1,000-year-old oaks used to create 'super forest'

- Published

Planting more trees is one of a combination of solutions to combating climate change, but some trees are far better than others. Which ones though? Scientists have designed an experimental forest in England to work out the best formula for achieving ambitious tree planting targets.

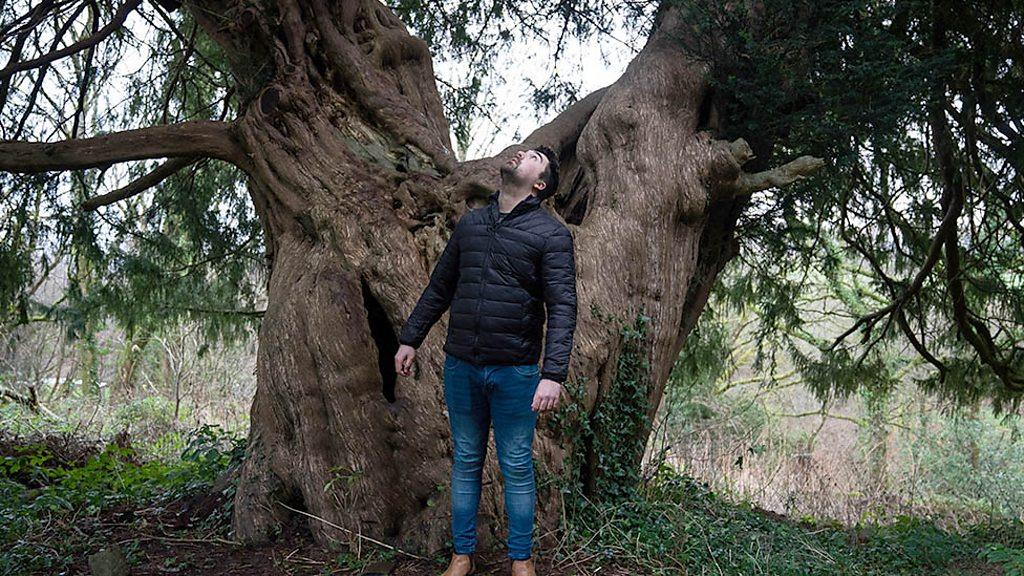

"They've lived for so long; just think what they've seen." Forester Nick Baimbridge is gazing fondly at a majestic oak that has stood for more than a thousand years. On this wintry afternoon, birds sing from lichen-covered branches and a deer runs through the undergrowth.

There's a sense of timelessness about this medieval forest, which contains the greatest collection of ancient oak trees anywhere in Europe. Blenheim Palace, a few miles away across the park, is a mere youngster at 300 years old, quips Baimbridge, the head forester of the Blenheim Estate.

The oldest oak in the forest is believed to be 1,046 years old

Standing under one of the oldest trees, he can only speculate on the turns of history witnessed by this "old girl", whose genetic heritage is set to live on through acorns collected from the forest floor.

The acorns, and the new generation of oaks they spawn, are crucial to the ambitions of an experimental "super forest" that is being planted where the rivers Dorn and Glyme wind their way through the Oxfordshire countryside.

The forest is spread across nine new neighbouring woodlands with the first trees planted out this winter.

The Blenheim Estate has received a government grant of about £1m to plant 270,000 trees in the nine new woodlands covering 1sq km (0.4 miles) in an inaugural scheme paying landowners to create forests with public access.

The autumn of 2020 was a "mast year," when the oaks produced a bumper crop of acorns, and foresters picked them off the forest floor and took them to a tree nursery on the estate, where they were planted into pots and left to grow. "We put them in compost and just wait for them to do their thing," says Baimbridge.

A new sapling growing at the nursery - a number of trees are raised, including sweet chestnut, beech and oak

The saplings take several years to grow big enough to be planted out in the forest, but experts think it is worth the wait to harness the pedigree of the Blenheim oaks.

These native oak trees, which can support hundreds of different species of insects, birds and fungi, will be needed in the race to reforest the UK. Britain remains one of the least wooded parts of Europe, and while new trees are being planted, ancient woodland continues to be lost. The government needs to treble tree planting efforts to meet its goal of creating 30,000 hectares of new woodland every year in the UK by 2025.

But it's not enough to randomly plant millions of trees; forests must be built to last, with a combination of species that will provide habitat for wildlife as well as absorbing carbon emissions.

Despite the fervour for planting trees, scientists warn it's not a "silver bullet" for tackling climate change. If not done with utmost care, the rush to plant trees can harm biodiversity and block land needed for other essential functions, such as growing food. And natural woodlands that contain a mixture of native species are more resilient and better for wildlife than vast plantations made up of one type of tree.

The ethos behind the so-called 'super forest' is to develop a formula for planting woodlands that can soak up carbon emissions, provide space for nature and people, and yield timber that will help trees pay their way.

The recipe they've come up with is to plant no less than 27 different types of tree, including conifers for absorbing carbon, a mixture of broad-leafed and native trees for biodiversity (the oaks are broad-leafs), as well as trees that will supply valuable wood.

Saplings from the ancient oaks will be planted on main paths and at entrances, and in clumps among the other native trees.

The woodlands will be scientifically monitored to assess their effectiveness at removing carbon emissions, enhancing biodiversity, and cleaning up air and water.

Oaks, hornbeams, limes, sycamore and other saplings are already in the ground, with the first phase of planting expected to be finished this month.

New shoots grow in the ancient woodland near Blenheim Palace

You might want trees everywhere for absorbing carbon, but that comes at the expense of other functions of the land, says Dr Casey Ryan of the University of Edinburgh. "That can be because you need that land for something else - probably agriculture in many cases, and we need to feed the world at the same time."

Kathy Willis, professor of biodiversity at the University of Oxford, has had oversight of the plans and approach to the new woodlands. She says the Blenheim team has considered all aspects of "natural capital" - the Earth's natural assets - from reducing flood risk to providing a habitat for birds and bees. Trees "can do fantastic things for biodiversity, but also carbon drawdown," she says.

It's not just the government that is funding these experimental woodlands. The Morgan Sindall Group, which builds homes, schools and retail premises, is a partner in the project. A construction company might seem like an unusual bedfellow given the sizeable carbon emissions arising from the construction industry, but many businesses are trying to be more green by choosing to offset carbon emissions that can't be reduced in any other way, through tree planting schemes.

Graham Edgell of Morgan Sindall says the company wanted to "do the right thing" by creating woodlands in the UK with paths open to everybody. "It's not some gesture of writing a cheque and walking away; we're going to be with this woodland for 25 years as a minimum," he says.

Nathan Fall, Nick Baimbridge and Robert Burgess. The saplings will be tended for the next 25 years

So how are the new woodlands getting on? We visit the first woodland taking shape on a windswept valley carved out by the River Dorn. Nathan Fall of forestry company, Nicholsons, leads us through rows of tiny saplings emerging on what was once arable land.

England has been "woefully behind" on tree planting, he says, because of pressures on land. He hopes these woodlands will act as a template for future tree-planting efforts. "If we can say, look - there is a model that works both financially and from an asset value perspective, then this hopefully will encourage others to follow at scale."

It is hard to imagine what this place will look like in a century, when the trees are fully grown. But that is not a problem for Fall, who, as a forester, is always planning for the next generation. Down near the river there is a natural amphitheatre shielded from the wind that is set to become the site of a forest school. And it's good to think that when the new Blenheim oaks have grown to full size, they will be here for tomorrow's children to admire.

Follow Helen on Twitter, external

Photographs by Phil Coomes

- Published23 January 2022

- Published25 February 2022

- Published3 March 2022

- Published8 March 2022