Could super-sized heat pumps make gas boilers extinct?

- Published

- comments

Huge heat pumps could become a key part of the UK's green energy mix

The war in Ukraine has forced a rethink of where we get our energy from as Europe tries to wean itself off Russian gas. But could super-sized heat pumps help to heat thousands of homes and businesses? Two huge schemes are about to be switched on in Gateshead and London - and the hope is they could provide a greener and cheaper source of warmth.

"Coal mining was massive in the North East," says Jim Gillon, walking across a building site in Gateshead.

"And where we're standing there are six different mine workings beneath our feet."

Jim is the Energy Services Manager for Gateshead Council - and he's giving this former fossil fuel site a green makeover for an ambitious new heating scheme.

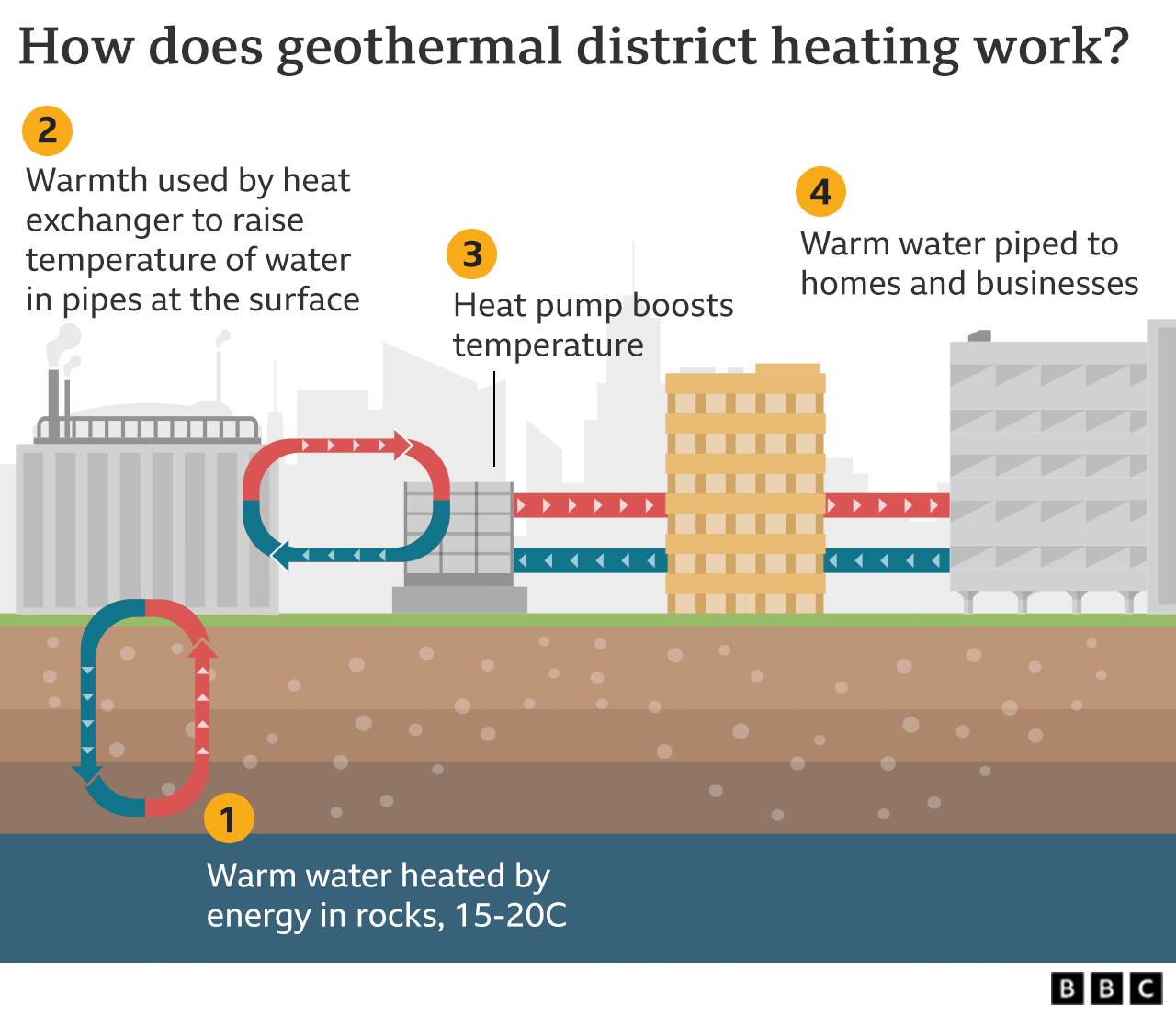

He points to a borehole that descends 150m beneath the muddy earth. Like many old coal mines, it's now flooded with water. But the water is naturally warm at 15C - and this heat is key.

The borehole in Gateshead reaches 150m beneath the ground into a disused coal mine

Just a few metres away, a giant heat pump has been installed.

It's a clever bit of engineering. In the same way that warmth can pass from one person to another when they shake hands, the warmth from the mine water is transferred into the closed heat pump system.

Through a series of processes a higher temperature, 80C, is reached and it's this heat that's sent out through pipes to be used by buildings in the local area. The mine water is sent back underground so the process can begin again.

The small, individual heat pumps that people install in their homes work using the same principle. They take some warmth - whether it's from the air or the ground - and then increase the temperature, providing heat for that one household.

But the heat pump in Gateshead is so large that at full capacity it can provide heat for the equivalent of 5,000 homes."We're really pleased that we've taken the legacy of the coal mining and we're turning that negative asset into a positive future source of energy," says Jim.

The buildings connected to the green district heating scheme have heat exchangers instead of boilers.

They shift the heat that arrives from the heat pumps to water in the pipes, to be used in kitchens and bathrooms and to run through radiators.

Jacqueline Bell had one installed in her Gateshead home about five years ago - it's linked in to another local low-carbon network.

She says that it involved a lot of upheaval to put in the new system, pipes had to be re-routed in the walls of her flat, but she's happy with the end result.

"I think my whole flat is much, much warmer than it used to be. And the cost is much, much cheaper too," she says.

The Citigen project is drilling down to an aquifer that lies under London's streets

Energy bills are a key concern for many consumers right now.

Gas prices were already rising steeply last year, but the war in Ukraine is pushing them to record highs as uncertainties grow over Europe's supply of gas that comes from Russia.

The hunt is on for alternatives sources of energy. Michael Lewis, CEO of EON UK, thinks green district heating schemes could help.

"They fundamentally change the landscape," he says.

"It means we get off natural gas. So not only is that a benefit for the climate, it also means our energy prices are no longer tied to the volatile international gas market."

The power plant in this historic building is going green. BBC Science Editor Rebecca Morelle explains how it works.

EON has installed its own super-sized heat pumps in the heart of London.

The Citigen plant is hidden behind the imposing facade of the Port of London Authority building. Over the years it's provided energy using first coal, then oil and more recently gas.

Now it will supply a renewable source of heat by tapping into the warm water from an aquifer that sits beneath the city.

"Heat pumps are low carbon because they are driven primarily by electricity - and in our case, the electricity will be renewable," explains Leke Oluwole, general manager at Citigen.

He says the scheme provides green heating to lots of buildings in one go.

"Rather than having 1,000 homes to decarbonise, you have one central location to decarbonise, which will help with the net zero goals that we have in the UK."

The Citgen heat pumps are about to be switched on

Heating the UK's 30 million buildings currently contributes nearly a quarter of our greenhouse gas emissions, according to the government's Heat and Building's Strategy.

"If we're going to tackle climate change then we really need to fundamentally rethink the way we heat our buildings," says Dr Fleur Loveridge from the University of Leeds.

For many homes, this will mean installing individual heat pumps. The government has announced ambitions for 600,000 to be installed every year by 2028.

But in places where housing is much more dense, green network heating schemes could be more suitable.

"District heating systems in the UK only accounts for around 2% of our heating at the moment," Dr Loveridge explains.

"If we're going to reach our net zero emissions by 2050, we probably need to increase that to around 18%."

"Green district heating is an absolutely essential feature of our future heating mix," she adds.

She says that the schemes aren't limited to places where there are flooded mines or aquifers - although there are many of these groundwater sites found across the UK.

"Anywhere where you can access the ground for the ground source heat will also work," she explains.

"Where you have surface water bodies, like rivers or lakes, that can also be made to work. Sea water has even been used to feed district heating systems.

"So it's applicable in a lot of places, but not absolutely everywhere."

The huge heat pumps in London and Gateshead will soon be switched on, and the warmth generated will start to flow into local homes and businesses.

But it's clear that these schemes are just the start. Many more will be needed if the UK is going to meet its climate change targets.