Climate change: Extreme weather warning systems for all 'in five years'

- Published

- comments

Early warning systems to protect the entire world from extreme weather and climate disasters should be rolled out within five years, according to the UN.

Right now, around one-third of the global population has no cover while in Africa 60% of the population is unprotected.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) will put together a plan on how this can be achieved by November.

Around $1.5bn will be needed to finance the development.

Over the past 50 years, a weather, climate, or water-related disaster has occurred on average every day.

As the world warms, these weather related extreme events are on the increase, going up five-fold over the past half-century.

Hurricane Ida caused enormous damage but few deaths as residents evacuated the path

But better warning systems have ensured that the number of people killed in these floods and storms has fallen significantly in the same period.

However, the scale of improvement depends very much on where you live.

Last year, when Hurricane Ida made landfall in Louisiana, it was the fifth strongest such storm to hit the continental US.

Thanks to effective forecasting and early warning, tens of thousands of people were mandated to evacuate and overall deaths were less than 100.

Contrast that with Cyclone Idai which hit Southern Africa in 2019, leaving around a thousand people dead across Mozambique, Malawi and Zimbabwe and millions more in need of humanitarian assistance.

While warnings were issued, the dissemination of the information, particularly in rural areas was not effective.

Cyclone Idai brought dramatic flooding to Mozambique and other countries in the region

"This is unacceptable, particularly with climate impacts sure to get even worse," said UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres in a video statement to launch the new plan.

"Early warnings and action save lives. We must boost the power of prediction for everyone and build their capacity to act."

The UN has now asked the WMO to develop a scheme so that early notifications of these type of extreme events can cover everyone on the planet within five years.

The greatest need is in parts of Central and West Africa, in the Caribbean and in small island developing states in the Pacific.

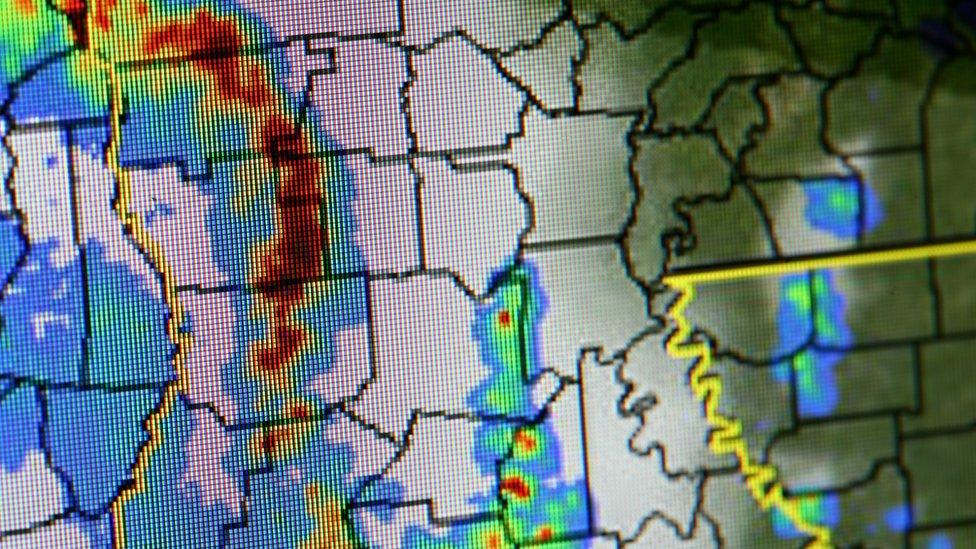

The WMO will look to put in place the technology that will involve real-time monitoring of the atmosphere so that people in these areas are made aware that a flood, a heatwave, or storm is on its way.

Crucially, the systems should also help inform governments, communities, and individuals on how to act to minimise damage.

The WMO estimates that it will cost around $1.5bn to improve the meteorological warning systems and build the knowledge in the least developed countries.

Weather warning systems should cover everyone on the planet within five years

The money will be raised from funding institutions like the World Bank and the Green Climate Fund.

"It will not be easy, it will be challenging, but when one looks at the potential costs of mobilising the resources to make this a reality, it's a mere fraction, a mere rounding error of the $14tn mobilised by G20 countries over the last two years to recover their economies from Covid-19," said a senior UN official.

Experts say that this type of spending repays itself in a very short time.

According to the Global Commission on Adaptation, external, an investment of $800m can result in avoided losses of as much as $16bn, which is 20 times the initial outlay.

Campaigners have welcomed the idea of better warning systems but believe it's the least that the richer world can do for countries that are living with the impacts of a warmer climate.

"The early warning systems are vital in saving lives but we must not stop at just preventing deaths," said Mohammed Adow from the campaign group Power Shift Africa.

"If people survive a climate disaster but then are left to fend for themselves with their homes and livelihoods destroyed, it's a meagre blessing.

"The global community needs to ensure the victims of climate catastrophes are helped to thrive, not just survive."

The WMO proposals will be unveiled at COP27 in Egypt in November.

Follow Matt on Twitter @mattmcgrathbbc, external.