Make Uranus mission your priority, Nasa told

- Published

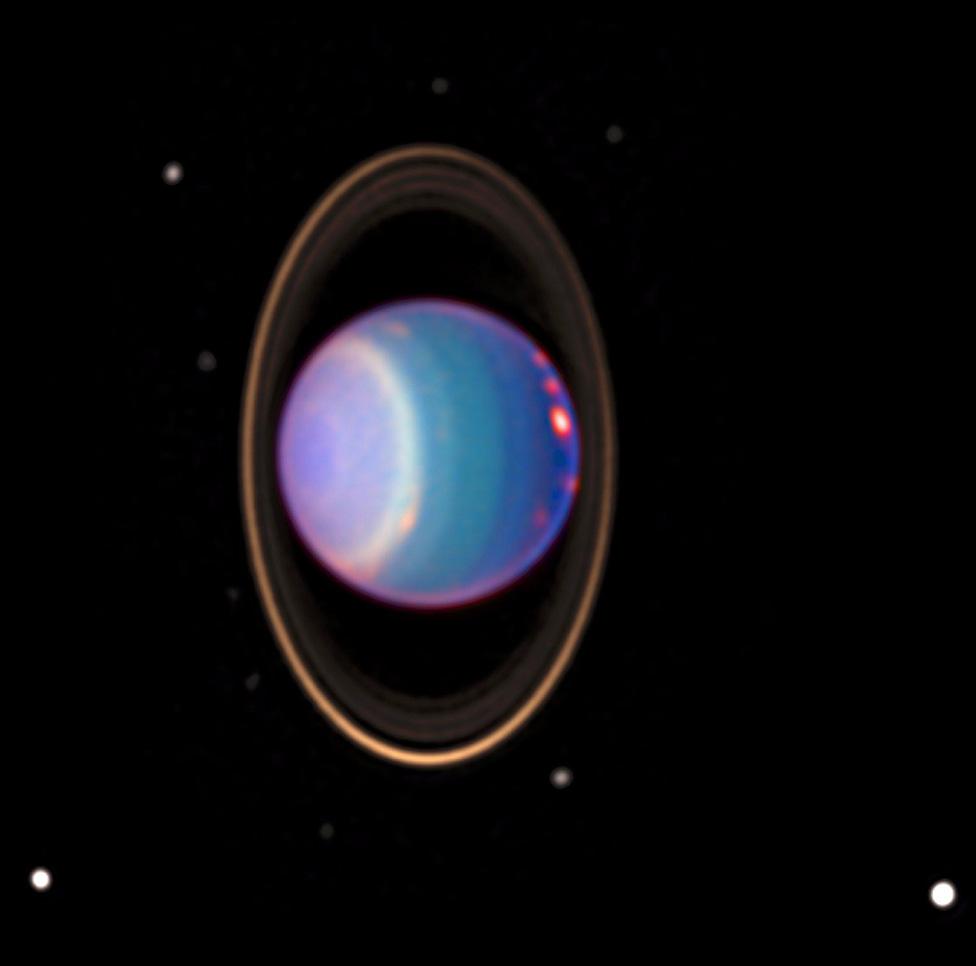

Uranus, photographed here by the Hubble Space Telescope, has at least 13 rings and numerous moons

The US space agency Nasa should prioritise a mission to Uranus, an influential panel of scientists says.

The "ice giant" is the seventh planet in our Solar System, orbiting the Sun 19 times further out than the Earth.

It's only ever been visited once before, in a brief flyby by the Voyager-2 probe in 1986.

Researchers think an in-depth study of Uranus can help them better understand the many similarly sized objects now being discovered around other stars.

The recommendation is made in a document, external published by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS).

Known as a "decadal survey", it is the summation of what the American research community thinks are the big planetary science questions right now and the space missions required to answer them.

Nasa has broadly followed the recommendations of previous National Academies reports.

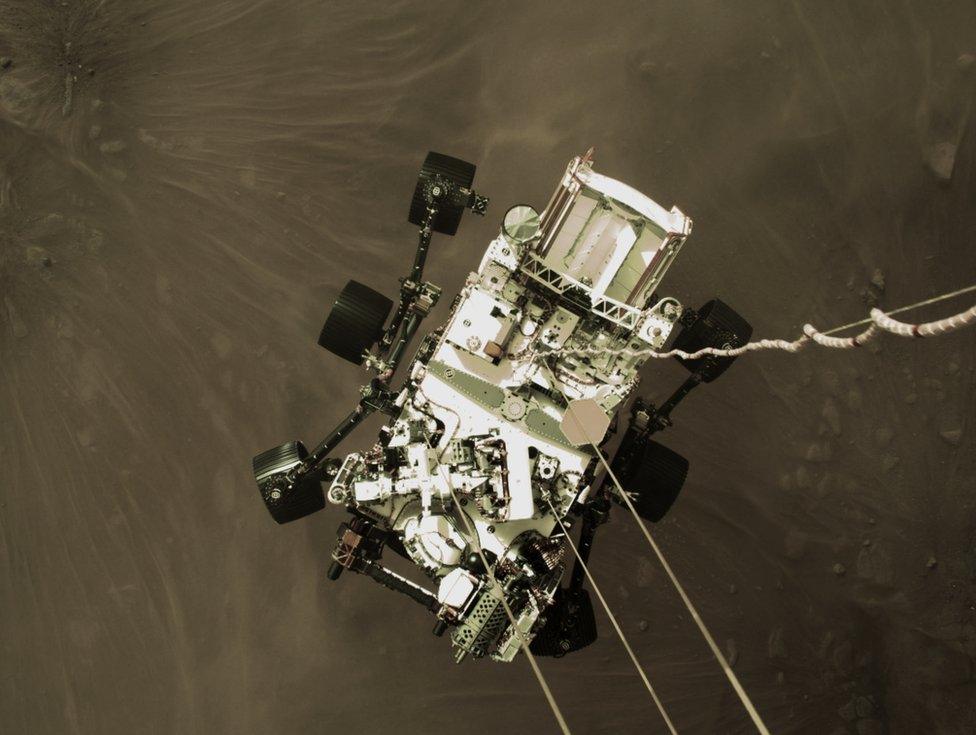

The last planetary decadal survey, external, published in 2011, had as its two top priorities a rock-collection mission to Mars, which became the Perseverance rover, now on the surface of the Red Planet; and a mission to Jupiter and its moon Europa, which is currently being prepared for launch in 2024. This is called the Europa Clipper spacecraft.

The closest we've been to Uranus is with the Voyager-2 mission

Uranus: Seventh planet from the Sun

Discovered by Sir William Herschel in 1781

Average distance from the Sun is 3 billion km

It circles the Sun once every 84 Earth years

Its diameter is four times that of our planet

Hydrogen and helium dominate the atmosphere

It has at least 13 rings and numerous moons

Specialists who study the outer planets in our Solar System have been campaigning for a return visit to either Uranus or Neptune ever since their late-80s Voyager-2 encounters. And the science case has only strengthened over the intervening years, proponents argue.

Look at the size-range of planets now being discovered around other stars and they seem to dominate in a range that's about three and four times the width of the Earth. That's Uranus and Neptune.

"And that actually poses a problem for planet formation theories," explained Prof Leigh Fletcher, who contributed to the report.

"We think we understand how something gets as big as Jupiter, and we think we understand how something gets to be the size of Earth and Venus. But in the middle, in that kind of sweet spot between those end-members - we don't fully understand how a world can start to grow and grow and not just carry on to become Jupiter-mass in size. A mission to Uranus could help us answer that," the Leicester University, UK, scientist told BBC News.

Artwork: European scientists will hope they can join the mission, just as they did with the Cassini mission to Saturn

There are favourable launch opportunities in 2031 and 2032 that would allow a spacecraft to use a gravity slingshot around Jupiter to shorten the cruise time to Uranus to "just" 13 years.

The spacecraft would go into orbit around the planet, which would preclude any observations at the more-distant Neptune. The eighth and outermost planet will have to wait its turn.

Uranus is an oddity compared with the other planets in the Solar System in that its axis of rotation is almost parallel with the plane of its orbit around the Sun. It's as if it has been knocked on to its side, which may well be the explanation - scientists speculate that it suffered a massive impact with another body early in its history.

Uranus has rings and plenty of moons.

Indeed, the moons are quite a draw because a good many of them are likely to be "ocean worlds".

"This is the idea that you've got an icy crust and then you've got some kind of liquid briny ocean down at depth that may or may not be in contact with whatever silicate rocky material is down at the bottom," said Prof Fletcher.

"Well, all of the big five classical satellites of Uranus are thought of as being ocean world candidates. These moons could have cryo-volcanic (ice volcano) activity taking place on them."

The successful completion of the Perseverance rover's mission comes before all else

Dr Robin Canup from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, was the co-chair on the Academies' steering committee.

She said an ice giant was a worthy target for a Nasa flagship and of all the potential candidates assessed in what would be the most expensive class of endeavour, the Uranus mission was the most mature technically.

"It was the only one to receive a low-medium rating for its risk," she explained.

"So because of that, we are extremely excited to recommend that the highest priority new flagship should be a Uranus orbiter and probe. This will be a fantastic multi-year mission with the probe dropping into the planet at the beginning of the mission, followed by an extended orbital tour investigating the satellites, their interiors, the magnetosphere, the rings, and the atmosphere.

"It is technically ready to start now. We recommend that it be initiated in financial year 2024."

European-based planetary researchers, like Prof Fletcher, will be hoping the European Space Agency (Esa) can contribute to such a mission.

Nasa and Esa are frequent partners, such as on the Cassini-Huygens mission to Saturn (2004-2017), but their priorities and funding cycles do not always coincide.

And for Nasa, the speed at which it's able to implement the recommendation will depend on its other financial commitments.

The decadal survey panel said completing the Perseverance rover's objectives and the follow-up missions designed to bring its rock samples back to Earth came before everything else in importance.