James Webb Space Telescope in final stretch

- Published

James Webb, astronomy's new super space telescope, has taken another major step to full operational capability.

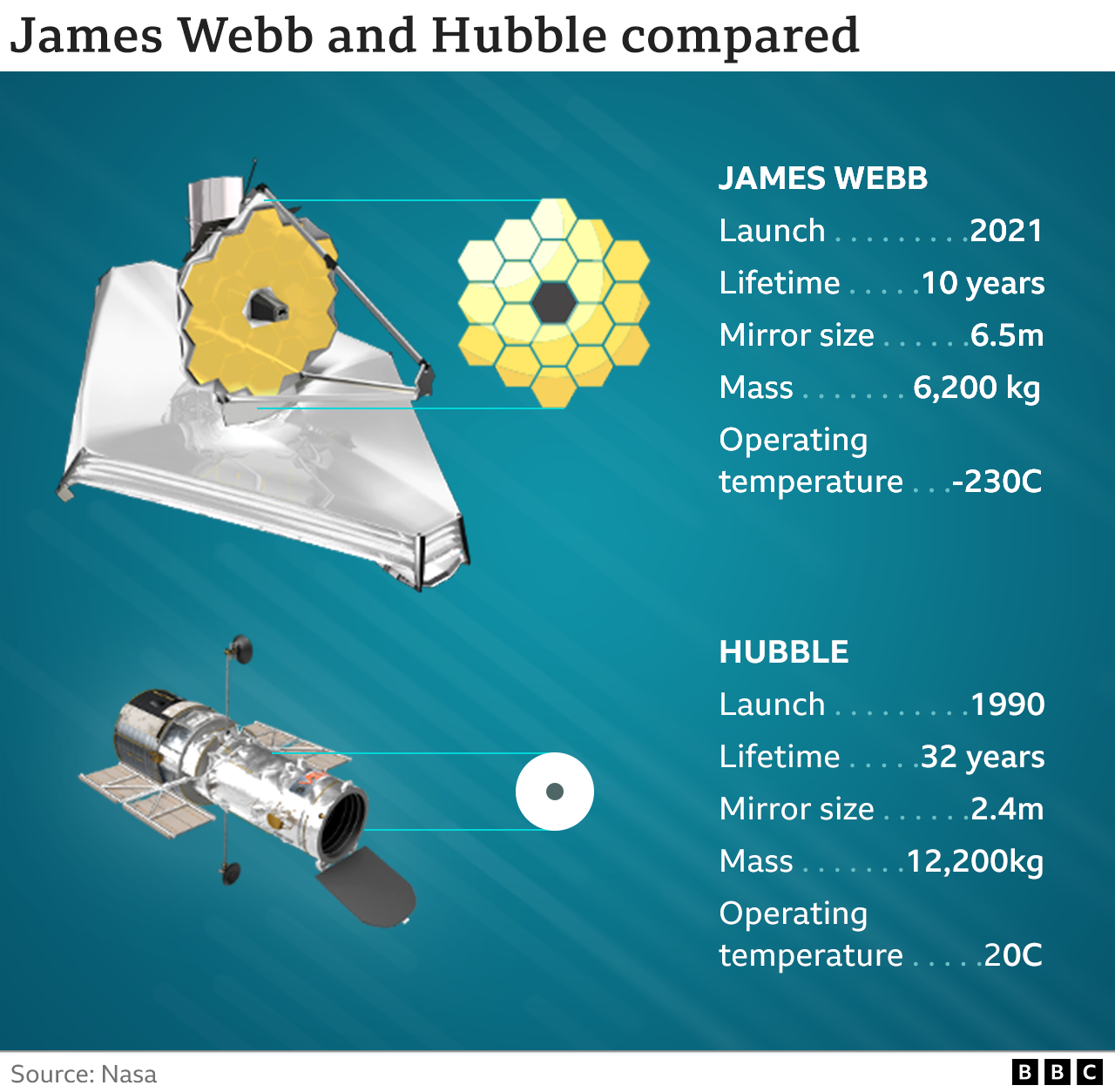

The $10bn successor to the Hubble Space Telescope is now fully focused and aligned. Light bounces perfectly off its mirrors to form pin-sharp imagery in all four of its instruments.

It just remains to check that the instruments are properly calibrated - that they are delivering their data in a way that's expected and understood.

This should take a couple more months.

Once this is done, James Webb will be ready to wow us with vistas that will be every bit as compelling as those produced by Hubble these past three decades.

"We've now reached the end of the telescope alignment phase - we've delivered perfectly focussed images to all of the science instruments," explained Prof Mark McCaughrean, senior science advisor for the European Space Agency.

"Now we're ready to check the many complicated ways each of them can catch the telescope's light and do the amazing science we dreamed of more than 20 years ago," he told BBC News.

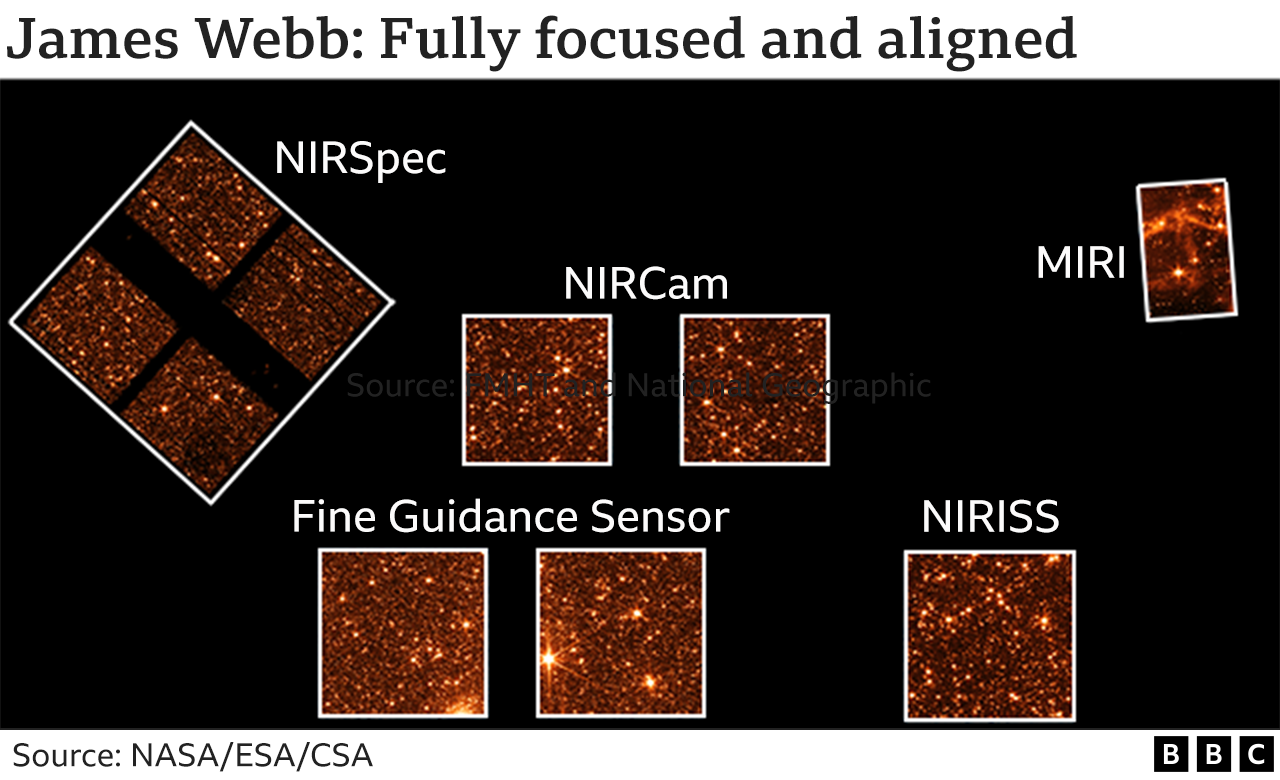

The US space agency Nasa, which leads the Webb project, released a set of engineering pictures on Thursday.

They're not intended to be exciting; they're merely a demonstration that all the hardware is working as it should.

The images show slightly different views of the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small satellite galaxy of our Milky Way.

In view are the points of light made by hundreds of thousands of stars.

The sizes and positions of the images depict the relative arrangement of each of Webb's instruments as they pick up the light coming from the telescope's golden mirrors, including from its 6.5m-wide primary reflector.

Nasa had previously released a sample of this type of imagery for the NIRCam instrument. NIRCam, which is Webb's main camera system, was used to do the initial focusing of the observatory's optics. When that job was complete, engineers had to work through each of the other three instruments (NIRSpec, MIRI and FGS/NIRISS) to confirm that NIRCam's alignment worked just as well for them.

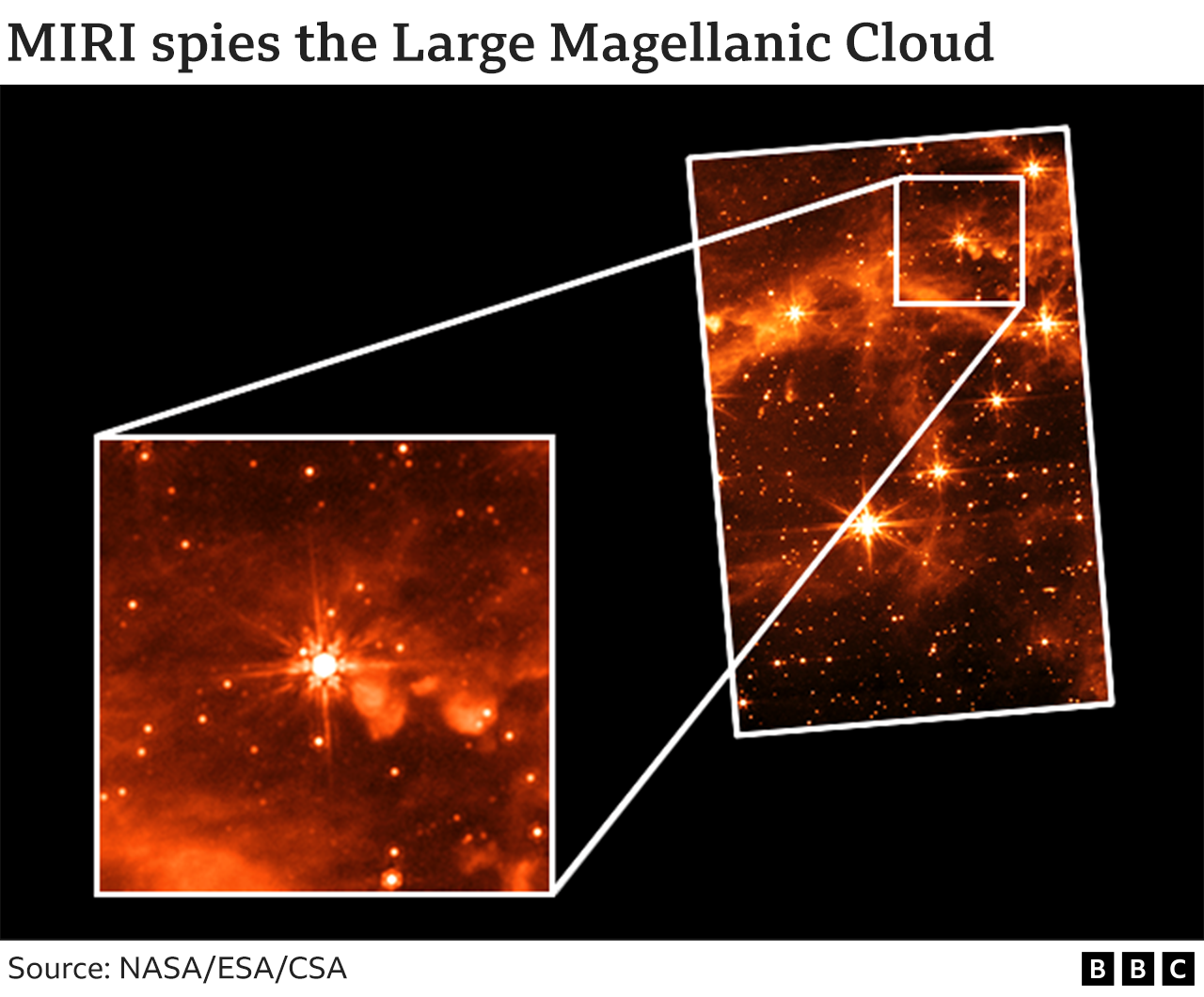

The last instrument to go through this process was MIRI, the Mid-Infrared Instrument whose development was led in part from the UK.

There will be elation today across a host of contributing British institutions to see MIRI's first published image.

If the picture looks slightly fluffy compared with those from the other instruments, it's because MIRI works at longer infrared wavelengths. The puffiness that surrounds the stars is the glow from carbon-rich (organic) molecules in the Large Magellanic Cloud. MIRI's particular sensitivity allows it to tease out different features in the field of view from its instrument counterparts.

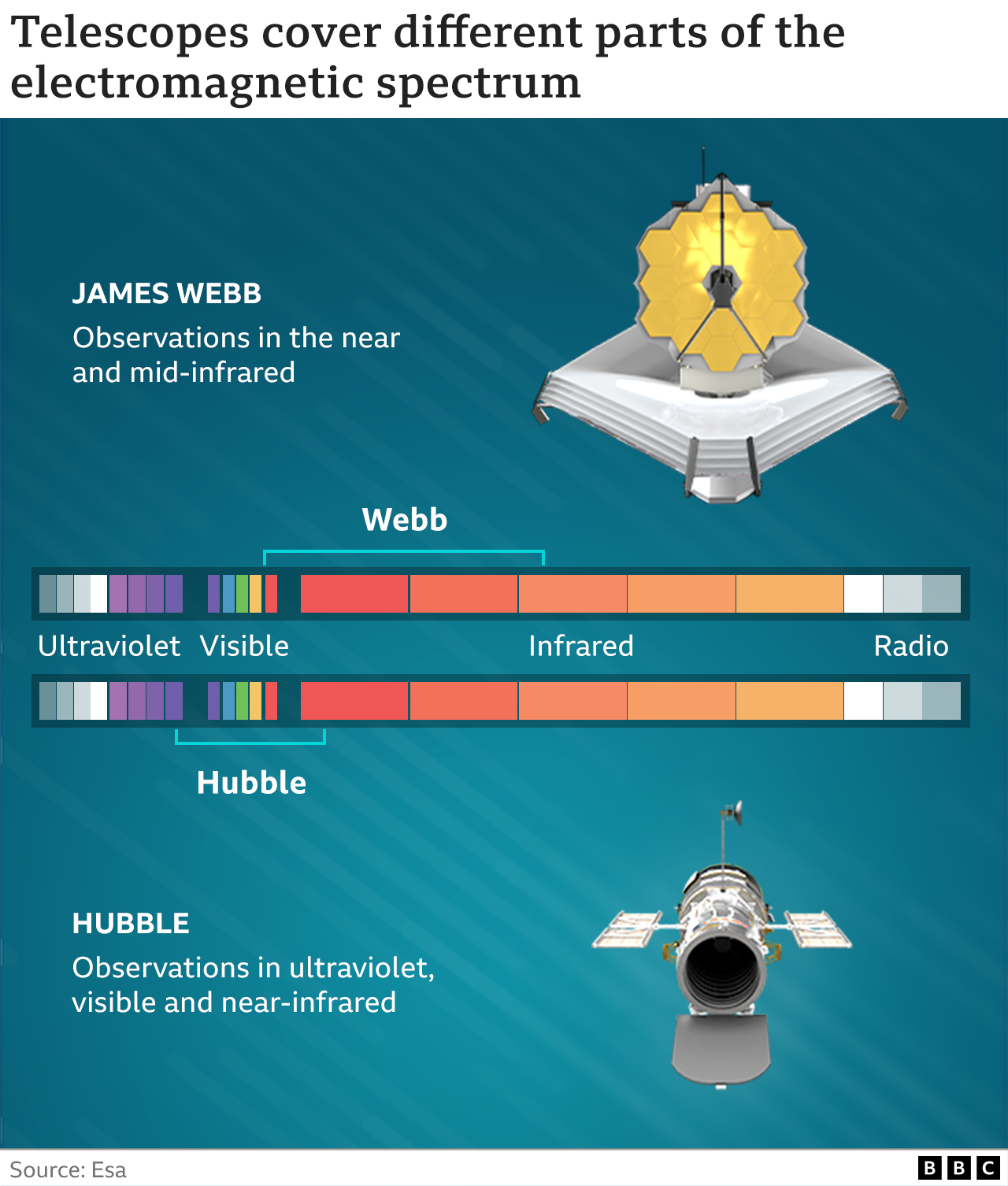

Scientists intend to use Webb and its remarkable 6.5m-wide mirror to capture events that occurred just a couple of hundred million years after the Big Bang. They want to see the very first stars to light up the Universe.

They'll also train the telescope's big "eye" on the atmospheres of distant planets to see if those worlds might be habitable.

A joint endeavour of Nasa, Esa and the Canadian Space Agency, Webb is the biggest telescope ever sent into space.

It's so big it had to be folded to fit inside the rocket that took it to orbit. The past four months have been spent unpacking and setting up the hardware. Before launch, many people were worried that Webb's complexity would lead quickly to technical problems. But far from it; engineers have worked through their to-do list like it was a simulation.

"This is the payback for having done things carefully and properly on the ground. And it's just fantastic," said Prof Gillian Wright, the co-principal investigator for MIRI.

"The whole team is buzzing at seeing it all come together. At launch we didn't have an observatory, we've got an observatory now," the director of the UK Astronomy Technology Centre in Edinburgh told BBC News.