Scottish astronomers push James Webb deeper back in time

- Published

The Edinburgh galaxy is the latest in a succession of "most distant" observations from Webb

Scottish astronomers have spied what they believe to be the most distant galaxy ever observed, using the new super space telescope, James Webb.

The red smudge is 35 billion light-years away. We see it, as it was, just 235 million years after the Big Bang.

It's a preliminary, or "candidate", result and will need a follow-up study for confirmation.

But for the moment, the University of Edinburgh team is celebrating and marvelling at James Webb's power.

"We're using a telescope that was designed to do precisely this kind of thing, and it's amazing," said Callum Donnan, an astrophysics PhD student in the university's Institute for Astronomy.

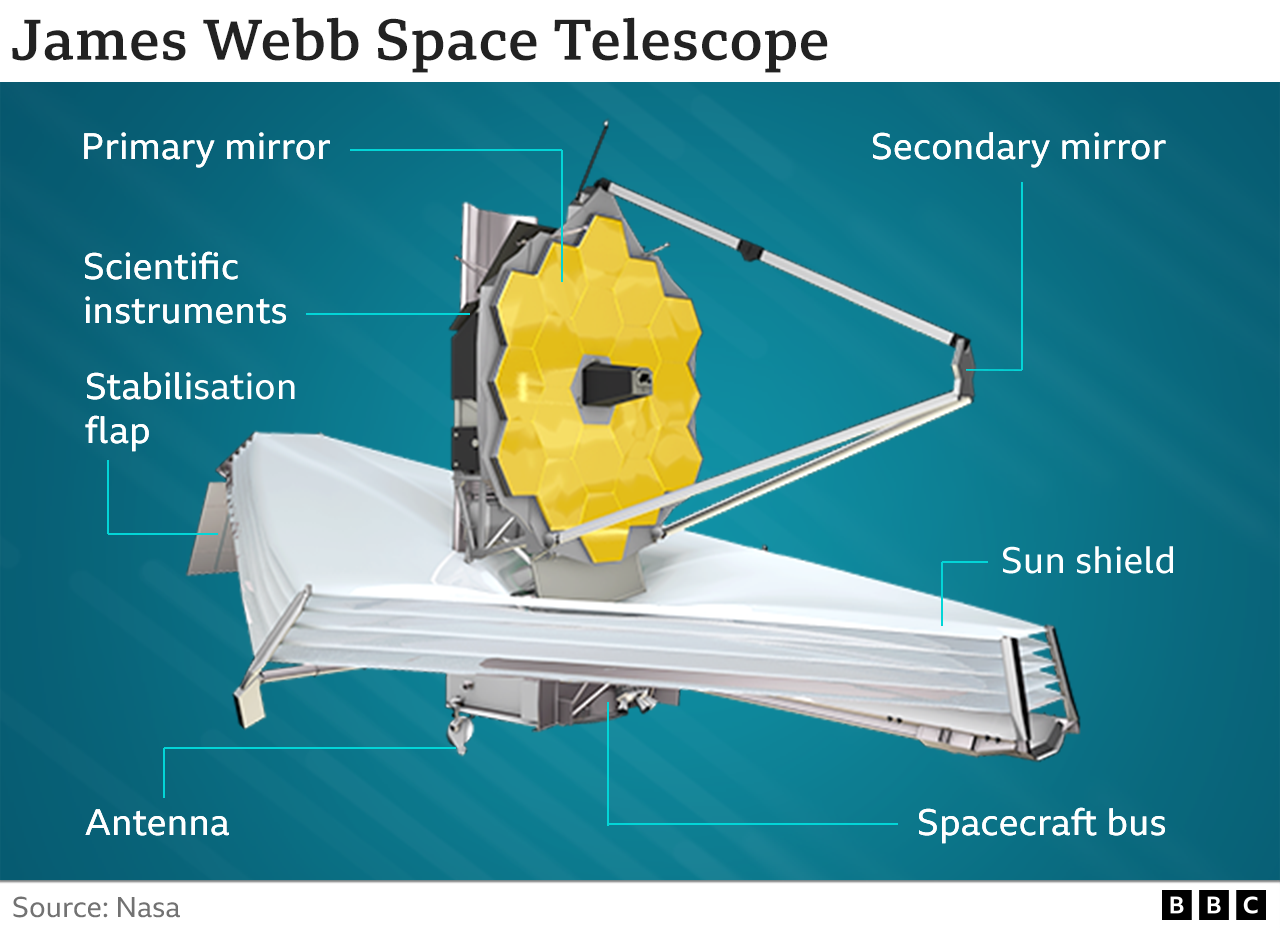

James Webb is the $10bn successor to the Hubble Space Telescope and is hunting the first stars and galaxies to form in the 13.8-billion-year-old Universe.

These objects are extremely faint but the new observatory has been tuned specifically to pick up their glow in infrared light.

Edinburgh's high mark will almost certainly be short-lived.

Since Webb began science operations at the end of June, astronomers have been finding ever more distant candidates in its imagery.

And if the designed performance is achieved, scientists could eventually see objects with Webb that were in existence perhaps as little as 100 million years after the Big Bang.

So we should expect a succession of announcements in the weeks and months ahead.

The Edinburgh target is called CEERS-93316 and is said to have a redshift of 16.7, external.

Redshift is the term astronomers use when discussing distances in the cosmos.

It's a measure that describes the way light coming from an object has been "stretched" by the expansion of the Universe to redder wavelengths.

The higher the redshift number assigned to a galaxy, the more distant it is and the earlier it is being viewed in cosmic history.

Recent days have seen a stream of ever larger redshift numbers being reported on the popular arxiv pre-print server.

Maisie's Galaxy was found in a wide-field survey being conducted by James Webb

The last 24 hours have been a good example of how fast things can move.

The Edinburgh group pulled its target from a wide-field survey of the sky that Webb is currently conducting called the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey, external.

The team that actually runs this survey put out its own far-distant candidate on Monday called CEERSJ141946.35+525632.8.

Dubbed Maisie's Galaxy, external after an astronomer's daughter, this target has a redshift of 14.3, which means it's being seen about 280 million years after the Big Bang. Not quite as far as CEERS-93316 but still a remarkable prospect compared with the era before James Webb.

There is a big caveat to all this, however. The early candidates announced from Webb observations have yet to undergo full spectroscopic examination.

This process slices up the light coming from a galaxy to reveal its component colours - its spectra. These will give the clearest view of how the light, which was originally emitted at visible wavelengths, has been stretched into the infrared over the course of cosmic history.

Only after this task is completed - and Webb has the instruments to do it - will distance claims move on to a surer footing

Another benefit of spectroscopy is that it will reveal the composition of objects.

Theory says the very first stars were fuelled just by hydrogen, helium and a small amount of lithium - the elements created in the Big Bang.

Heavier atoms - astronomers call them all "metals" - had to be forged in those pioneer stars and their descendants.

"We can look at the colours in our galaxy in a broad sense, and it's quite blue, which suggests a young stellar population. But it's not blue enough that this galaxy is made up of metal-free stars," Mr Donnan said.

It is Prof Steve Finkelstein, from the University of Texas at Austin, US, who is the proud father of Maisie.

He will be a guest on Thursday's Science In Action programme on the BBC World Service.

"I had heard a quote for this telescope that it is going to be transformative. And I said, 'you know, it's gonna do a lot of really cool things, but is it really going to completely change the way we view the Universe? I couldn't have been more wrong. Textbooks are going to be rewritten on even just the data we've gotten in the first week."

Note on distances: The Universe is expanding. In the time the light from objects takes to reach us, those objects have receded greatly. Their positions today, therefore, are much, much further away than when the light was first emitted.