Climate change: More studies needed on possibility of human extinction

- Published

Catastrophic climate change outcomes, including human extinction, are not being taken seriously enough by scientists, a new study says.

The authors say that the consequences of more extreme warming - still on the cards if no action is taken - are "dangerously underexplored".

They argue that the world needs to start preparing for the possibility of what they term the "climate endgame".

They want UN scientists to investigate the risk of catastrophic change.

According to this new analysis, external, the closest attempts to directly understand or address how climate change could lead to global catastrophe have come from popular science books such as The Uninhabitable Earth and not from mainstream science research.

In recent years climate scientists have more often studied the impacts of warming of around 1.5C or 2C above the temperatures seen in 1850, before the onset of global industrialisation.

These studies show that keeping temperatures close to these levels this century will place heavy burdens on global economies, but they do not envisage the end of humanity.

Researchers have focussed on these lower temperature scenarios for good reasons.

The Paris climate agreement saw almost every nation on Earth sign up to a deal that aims to keep the rise in global temperatures "well below" 2C this century, and make efforts to keep it under 1.5C.

People flee from flood waters in Pakistan

So it's natural that governments would want their scientists to show exactly what this type of change would mean.

But this new paper says that not enough attention has been given to more extreme outcomes of climate change.

"I think it's sane risk management to think about the plausible worst-case scenarios and we do it when it comes to every other situation, we should definitely do when it comes to the fate of the planet and species," said lead author Dr Luke Kemp from the University of Cambridge.

The researchers found that estimates of the impacts of a temperature rise of 3C are under-represented compared to their likelihood.

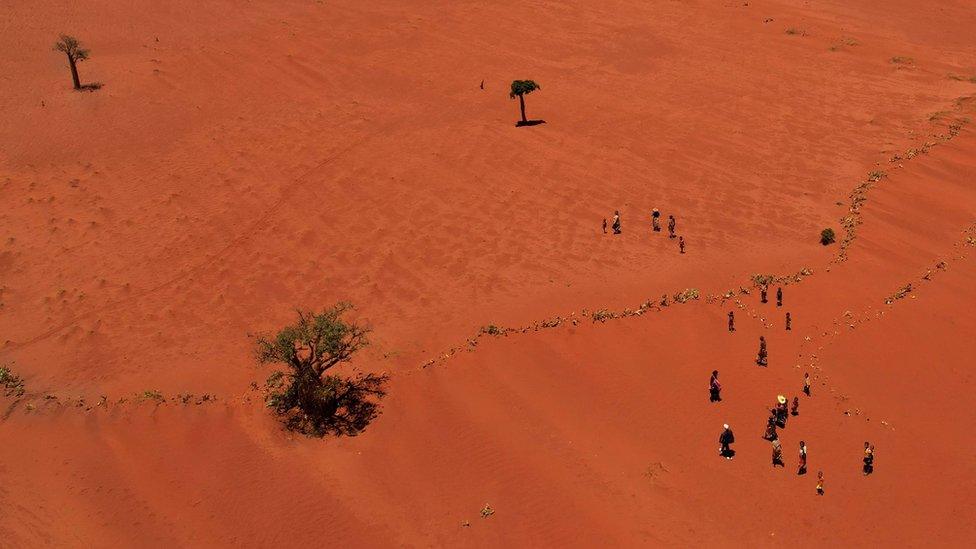

Using climate models, the report shows that in this type of scenario, by 2070 around 2 billion people living in some of the most politically fragile areas of the world would be enduring annual average temperatures of 29C.

"Average annual temperatures of 29C currently affect around 30 million people in the Sahara and Gulf Coast," said co-author Chi Xu of Nanjing University.

"By 2070, these temperatures and the social and political consequences will directly affect two nuclear powers, and seven maximum containment laboratories housing the most dangerous pathogens. There is serious potential for disastrous knock-on effects," he said.

The future impacts of extreme climate change have not been fully explored

The report says that it is not just high temperatures that are the problem, it's the compound and knock-on effects such as food or financial crises, conflicts or disease outbreaks that have the potential for disaster.

There should also be more focus on identifying potential tipping points, where increasing warmth triggers another natural event that drives temperatures up even more - such as methane emissions from melting permafrost or forests that start emitting carbon rather than soaking it up.

To properly assess all these risks, the authors are calling on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, external to carry out a special report on catastrophic climate change.

The researchers said that seriously studying the consequences of worst-case scenarios was vital, even though it might scare people.

They said that carrying out this research would allow scientists to consider emergency options such as climate engineering which might involve pumping coolants into the atmosphere. Researchers would be able to carry out a risk analysis for these drastic interventions compared to the worst effects of climate change. Focussing on the worst-case scenarios could also help inform the public - and might actually make the outcomes less likely.

"Understanding these plausible but grim scenarios is something that could galvanise both political and civil opinion," said Dr Kemp.

"We saw this when it came to the identification of the idea of a nuclear winter that helped compel a lot of the public efforts as well as the disarmament movement throughout the 1970s and '80s."

"And I hope if we can find similar concrete and clear mechanisms when it comes to thinking about climate change, that it also has a similar effect."

The plea for serious study of more extreme scenarios will chime with many younger climate activists, who say they are often not addressed for fear of frightening people into inaction.

"It is vital that we have research into all areas of climate change, including the scary reality of catastrophic events," said Laura Young, a 25-year-old climate activist. "This is because without the full truth, and all of the potential impacts, we won't make the informed choices we need, and we won't be driving climate action with enough pressure.

"For years climate change has been hidden, misinformed, and avoided and this has to stop now. Especially for the younger generations who are going to be left to deal with the consequences of years of pushing the Earth to its limits."

The study , externalhas been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

BBC News Climate and Science reporter Ella Hambly contributed to this report.